Heart disease is often touted as a purely modern affliction that is brought on by modern society’s increasingly sedentary lifestyles and high-fat diets. Recent scans of a 3,500-year-old mummy might be causing many of us to revise that belief.

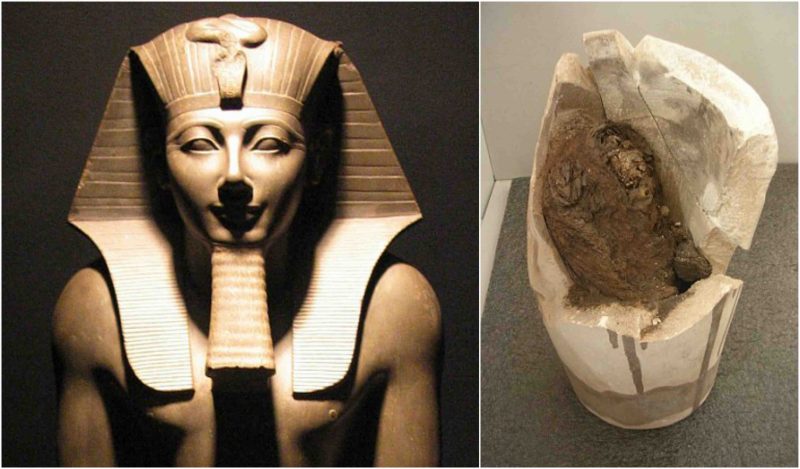

The mummy was once an Egyptian man called Nebiri, who worked as the Chief of Stables during the reign of Thutmoses III, a pharaoh from the 18th Dynasty of ancient Egypt. His tomb was located in Luxor and opened back in 1904 by Egyptologists. During his life, Nebiri would have belonged to the elite social class.

Now, the mummified head and lungs of Nebiri have been scanned, and they have been found to show classic signs of cardiovascular disease that modern patients suffer from. According to researchers, this is the oldest case of chronic heart failure ever to be discovered.

These findings also add to the other research done on Egyptian mummies that suggest heart disease was rife in the ancient society. For example, in 2008, cardiologists studied the chest of the mummy of King Merneptah, a pharaoh who ruled around 3,200 years ago, and they reported finding a buildup of fatty plaque on the inside of the mummy’s arteries.

In 2011, Cardiologists at Cairo’s Al Azhar University found that the Egyptian Princess Ahmose-Meryet-Amon, who lived in Thebes between 1540 and 1550 BC, had calcium deposits in two main coronary arteries. The princess’ father and brother were both pharaohs. The mummy herself had pierced ears, as well as a large incision in her left side that had been made by embalmers to remove her internal organs after her death. At the time, treatment for heart disease, explained researchers, was little more than eating special herbs or honey. They added that had the princess been alive today, she would have needed open heart surgery.

Scans on other mummies have revealed that they too displayed the symptoms of heart disease, including arteriosclerosis, which is fatty buildup in the arteries. There is a similarity between all the mummies: they were all part of the Egyptian elite. They were the wealthiest and most powerful people of their time. This indicates that it was their lifestyle that lead to their heart problems. In Nebiri’s case, his had atherosclerosis in the right carotid artery. He also suffered from severe gum disease.

Dr. Raffaella Bianucci, a medical anthropologist at the University of Turin who presented the findings at the International Congress of Egyptologists in Florence, said, “Nebiri was middle aged — 45 to 60 years old — when he died and he was affected by a severe periodontal disease with several abscesses.”

Researchers took Nebiri’s canopic jars and reconstructed his internal organs. They found that his lungs contained with air sacs—these are called pulmonary oedema, where fluid accumulates in the lungs air sacs, and they are seen in many heart failure patients. In order to fully examine Nebiri and his condition at the time of his death, experts, hailing from the University of York and the University of Munich, used multi-detector computed tomography to reconstruct the mummy in three dimensions.

“There is evidence of calcification in the right internal carotid artery. It can be confidently concluded that Nebiri died from an acute cardiac failure after having experienced a chronic cardiac insufficiency.” Explained Dr. Bianucci. During an interview with Discovery News, the doctor said, “Our finding represents the oldest evidence for chronic heart failure in mummified remains. A systematic analysis of canopic jar content could help establish whether the disease was more frequent in our ancestors or its prevalence increased in modern times.”

Speaking to Mail Online, she added, “Indeed it is highly likely heart disease has origins as ancient as humankind. From a scientific point of view, this case shows to be important as it allows following the course of the disease until the demise of the individual in the absence of chemical treatment or surgery. More research is needed to provide indirect information about the prevalence of hypertension in Ancient Egypt, a data which is still unknown, and genetic predisposition to cardiovascular pathologies.”

Nebiri’s mummy was hardly the ideal specimen, but that hasn’t prevented researchers from gathering important data. Professor Joann Fletcher, an Egyptologist at the University of York who also took part in the study, noted, “The remains of Nebiri are quite minimal, his body had been broken up when his tomb was looted in antiquity, so when discovered the archaeologists discovered little more than his detached head and the canopic jars which held his internal organs removed during the embalming.” Professor Fletcher continued, “Yet his head is in superb condition — indicating a very high-quality embalming. Since one of the canopic jars was already broken when found, this allowed access to the organs within, in this case, his lungs, meaning we were able to take minute samples with the very minimal of disturbance.”

It’s a benefit that the scans are so unobtrusive, otherwise, the belief that heart failure is an exclusively modern disease would remain unchallenged. Now, we know that it doesn’t matter what era you live in, if you lead an unhealthy lifestyle, you will have to live with the consequences.