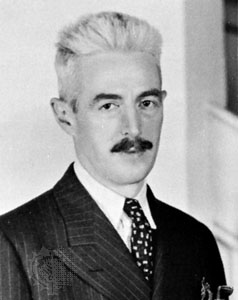

Dalton Trumbo

The blacklist era kicked off in 1947 when famed screenwriter Dalton Trumbo and several other filmmakers known as the “Hollywood Ten” were called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and asked a now-famous question: “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” Trumbo had indeed been a party member at one time, but like the rest of the Ten, he refused to answer and even questioned the legitimacy of HUAC in his testimony. As a result, he was charged with contempt of Congress, blacklisted by the Hollywood studios and sentenced to a year in federal prison. Following his release, Trumbo was forced to write under pseudonyms and sell his scripts on the black market. He secretly penned several classic screenplays during the 1950s including “Gun Crazy” and “The Brave One,” and his work even won two Academy Awards, neither of which he was able to collect. Trumbo finally broke free of the blacklist in 1960 after director Otto Preminger and actor Kirk Douglas announced that he would receive writing credit for the films “Exodus” and “Spartacus.” He later resumed his career in Hollywood, but it wasn’t until 2011 that the Writer’s Guild of America finally credited him with the Oscar-winning script for 1953’s “Roman Holiday.”

Pete Seeger

From the 1940s through the early 1970s, the US government spied on singer-songwriter Pete Seeger because of his political views and associations. According to documents in Seeger’s extensive FBI file — which runs to nearly 1,800 pages (with 90 pages withheld) and was obtained by Mother Jones under the Freedom of Information Act — the bureau’s initial interest in the musician was triggered in 1943 after Seeger, as an Army private, wrote a letter protesting a proposal to deport all Japanese American citizens and residents when World War II ended.

Seeger, a champion of folk music and progressive causes — and the writer, performer, or promoter of now-classic songs, including as “If I Had a Hammer,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” Turn! Turn! Turn!,” “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine,” “Goodnight, Irene,” and “This Land Is Your Land” — was a member of the Communist Party for several years in the 1940s, as he subsequently acknowledged(He later said he should have left earlier). His FBI file shows that Seeger, who died in early 2014, was for decades hounded by the FBI, which kept trying to tie him to the Communist Party, and the first investigation in the file illustrates the absurd excesses of the paranoid security establishment of that era.

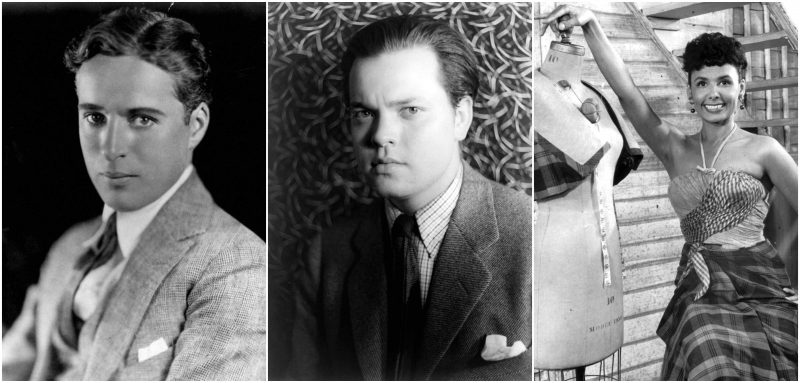

Orson Welles

At the same time that director, writer, and actor Orson Welles were making groundbreaking films and radio programs, he was also under FBI investigation as a potential Communist and political subversive. Welles was targeted in part because of his progressive political stances, but the suspicions only grew after the release of his classic 1941 film “Citizen Kane,” whose main character served as a thinly veiled reference to the anti-Communist news mogul William Randolph Hearst. “The evidence before us leads inevitably to the conclusion that the film ‘Citizen Kane’ is nothing more than an extension of the Communist Party’s campaign to smear one of its most effective and consistent opponents in the United States,” one FBI report read. While the Bureau never found evidence that Welles was himself a Communist Party member, it still added him to its index of people believed to be a threat to national security. His name would later appear in the 1950 “Red Channels” pamphlet, but by then he had already entered a long period of self-imposed exile in Europe.

Lena Horne

She was a goddess with a honey-sweet voice. “I remember once seeing her on a train,” says the jazz scholar and author Stanley Crouch. “She had a luminous restrained presence that most superstars try to pretend they have. She really had it.” In 1941 when she was 23, Horne was hired to perform at a unique club in Greenwich Village called Cafe Society Downtown. It was a “people’s nightclub,” wrote Buckley, Horne’s daughter, in her 1986 book, The Hornes: An American Family, and the only place in the city where the races mixed.

What few of the patrons knew was that the club was moving money for the Communist Party. They were distracted by the musicians and mesmerized by Horne’s beauty. She was learning to personify everything she sang, and to make eye contact with the audience, especially men. In November 1941, Harper’s Bazaar called her the queen of Cafe Society. She later said that most of what she knew about the music she absorbed there. Despite her brush with the blacklist, she remained a political activist and later took part in civil rights protests during the 1960s.

Charlie Chaplin

Though never a member of the Communist Party, silent screen icon Charlie Chaplin drew the ire of the government for his subversive films and support of leftist political causes. The “Little Tramp” creator skewered the capitalist and industrial society, as did other movies such as “Modern Times,” “The Great Dictator” and “Monsieur Verdoux,” and he was later denounced as a Communist sympathizer after he donated money to the defense fund for Dalton Trumbo and the Hollywood Ten. The FBI, meanwhile, compiled a file on Chaplin that was over 2,000 pages long. The tensions finally came to a head in 1952, when Chaplin — a British national — was denied his re-entry visa to the United States after a trip abroad. Told he’d need to testify to his “moral worth” before he could regain the permit, the director-actor instead cut ties with America and spent the rest of his career working in Europe. Save for a 1972 trip to collect an honorary Oscar, Chaplin never set foot in the United States again.

Lee Grant

In 1951 Grant gave an impassioned eulogy at the memorial service for actor J. Edward Bromberg, whose early death, she implied, was caused by the stress of being called before House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC). After her eulogy was published, she was summoned by the same committee to testify against her husband, playwright Arnold Manoff, but refused. As a result, for the next twelve years, her “prime years”, as she put it, she was blacklisted and unable to work in either television or movies.

By the time Grant’s name was finally removed from the blacklist in the early 1960s, she had since been divorced, remarried, and now had a young daughter, Dinah. Grant immediately tried to reestablish her television and movie career. Her experience with the blacklist scarred her to such an extent that as late as 2002, she would freeze and go into a “near trance” when anyone asked her about her experiences during the McCarthy period.

Dashiell Hammett

The man who helped create hardboiled fiction with detective novels such as “The Maltese Falcon” and “The Thin Man” was also an avowed anti-fascist and Communist Party member. After he wrote The Thin Man, Hammett never wrote another novel and dedicated himself to left-wing political causes, including civil rights. When Pearl Harbor was bombed during World War II, Hammett once again enlisted in the Army, after which he moved to New York, where his fortunes would take a turn for the worse.

Trouble with the law involving Hammett’s communist associates led him to serve a six-month jail sentence, after which the IRS came after him for $100,000 in back taxes. In 1953, Hammett found himself testifying before Joseph McCarthy’s Senate hearings that sought to root out Communists in the American entertainment industry, bringing added, unwanted, media attention to the writer. He soon moved to a cottage in Katonah, New York, where he lived an isolated life. After suffering a heart attack in 1955, Hammett died of lung cancer in New York City on January 10, 1961, at the age of 67.