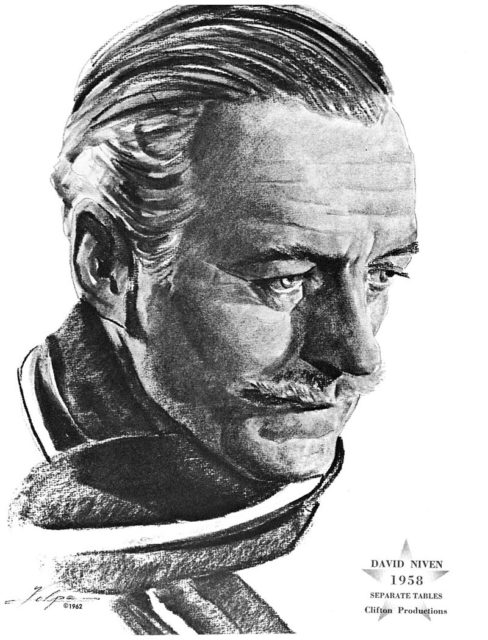

James David Graham Niven was a popular English actor and novelist. His many roles included Squadron Leader Peter Carter in A Matter of Life and Death, Phileas Fogg in Around the World in 80 Days, and Sir Charles Lytton, (“the Phantom”) in The Pink Panther. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in Separate Tables (1958).

Born in London, Niven attended Heatherdown Preparatory School and Stowe before gaining a place at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. After Sandhurst, he joined the British Army and was gazetted a second lieutenant in the Highland Light Infantry. Having developed an interest in acting, he left the Highland Light Infantry, traveled to Hollywood, and had several minor roles in films. He first appeared as an extra in the British film There Goes the Bride (1932). From there, he hired an agent and had several small parts in films from 1933 to 1935, including a non-speaking part in MGM’s Mutiny on the Bounty. This brought him to wider attention within the film industry and he was spotted by Samuel Goldwyn.

After Britain declared war on Germany in 1939, Niven returned home and rejoined the British Army. He was alone among British stars in Hollywood in doing so; the British Embassy advised most actors to stay. Niven was recommissioned as a lieutenant into the Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) on 25 February 1940, and was assigned to a motor training battalion. He wanted something more exciting, however, and transferred into the Commandos. He was assigned to a training base at Inverailort House in the Western Highlands. Niven later claimed credit for bringing future Major General Sir Robert E. Laycock to the Commandos. Niven commanded “A” Squadron GHQ Liaison Regiment, better known as “Phantom”. He worked with the Army Film Unit. He acted in two films made during the war, The First of the Few (1942) and The Way Ahead (1944). Both were made with a view to winning support for the British war effort, especially in the United States. Niven’s Film Unit work included a small part in the deception operation that used minor actor M.E. Clifton James to impersonate General Sir Bernard Montgomery. During his work with the Film Unit, Peter Ustinov, though one of the script-writers, had to pose as Niven’s batman (essentially his servant). Niven explained in his autobiography that there was no military way that he, as a lieutenant-colonel, and Ustinov, who was only a private, could associate, other than as an officer and his subordinate, hence their strange “act”. Ustinov later appeared with Niven in Death on the Nile (1978).

Niven took part in the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944, although he was sent to France several days after D-Day. He served in the “Phantom Signals Unit,” which located and reported enemy positions, and kept rear commanders informed on changing battle lines. Niven was posted at one time to Chilham in Kent. He remained close-mouthed about the war, despite public interest in celebrities in combat and a reputation for storytelling. He once said:

“I will, however, tell you just one thing about the war, my first story and my last. I was asked by some American friends to search out the grave of their son near Bastogne. I found it where they told me I would, but it was among 27,000 others, and I told myself that here, Niven, were 27,000 reasons why you should keep your mouth shut after the war.”

He had particular scorn for those newspaper columnists covering the war who typed out self-glorifying and excessively florid prose about their meager wartime experiences. Niven stated, “Anyone who says a bullet sings past, hums past, flies, pings, or whines past, has never heard one — they go crack!” He gave a few details of his war experience in his autobiography, The Moon’s a Balloon: his private conversations with Winston Churchill, the bombing of London, and what it was like entering Germany with the occupation forces. Niven first met Churchill at a dinner party in February 1940. Churchill singled him out from the crowd and stated, “Young man, you did a fine thing to give up your film career to fight for your country. Mark you, had you not done so it would have been despicable.”

A few stories have surfaced about David Niven’s time in the war: About to lead his men into action, Niven eased their nervousness by telling them, “Look, you chaps only have to do this once. But I’ll have to do it all over again in Hollywood with Errol Flynn!” Asked by suspicious American sentries during the Battle of the Bulge who had won the World Series in 1943, he answered, “Haven’t the foggiest idea … but I did co-star with Ginger Rogers in Bachelor Mother!” On another occasion, asked how he felt about serving with the British Army in Europe, he allegedly said, “Well on the whole, I would rather be tickling Ginger Rogers’ tits.”

Niven ended the war as a lieutenant-colonel. On his return to Hollywood after the war, he received the Legion of Merit, an American military decoration. Presented by Eisenhower himself, it honored Niven’s work in setting up the BBC Allied Expeditionary Forces Programme, a radio news and entertainment station for the Allied forces.

Niven resumed his career in 1946, now only in starring roles. His films A Matter of Life and Death (1946), The Bishop’s Wife (1947) with Cary Grant, and Enchantment (1948) are all highly regarded. In 1950, he starred in The Elusive Pimpernel, which was made in Britain and which was to be distributed by Samuel Goldwyn. Goldwyn pulled out, and the film did not appear in the US for three years. Niven had a long, complex relationship with Goldwyn, who gave him his first start, but the dispute over The Elusive Pimpernel and Niven’s demands for more money led to a long estrangement between the two in the 1950s.