Capone was in a street gang as a child.

Many New York gangsters in the early 20th Century came from impoverished backgrounds, but this was not the case for the legendary Al Capone. Far from being a poor immigrant from Italy who turned to crime to make a living, Capone was from a respectable, professional family.

But it was Capone’s schooling, both inadequate and brutal at a Catholic institution beset with violence that marred the impressionable young man. Despite having been a promising student, he was expelled at the age of 14 for hitting a female teacher, and never went back.

It was then that Capone met the gangster Johnny Torrio, who would prove the greatest influence on the would-be gangland boss. Torrio taught Capone the importance of maintaining a respectable front while running a racketeering business.

He hated his famous nickname.

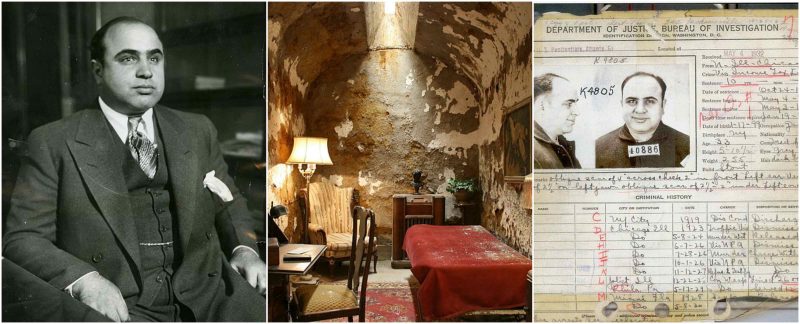

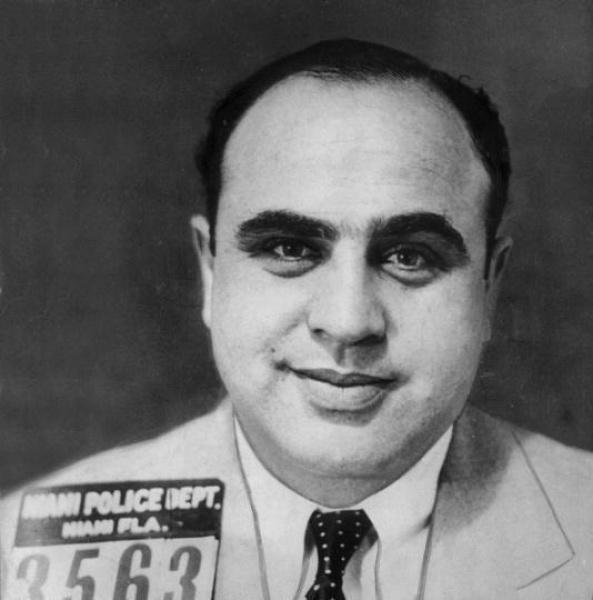

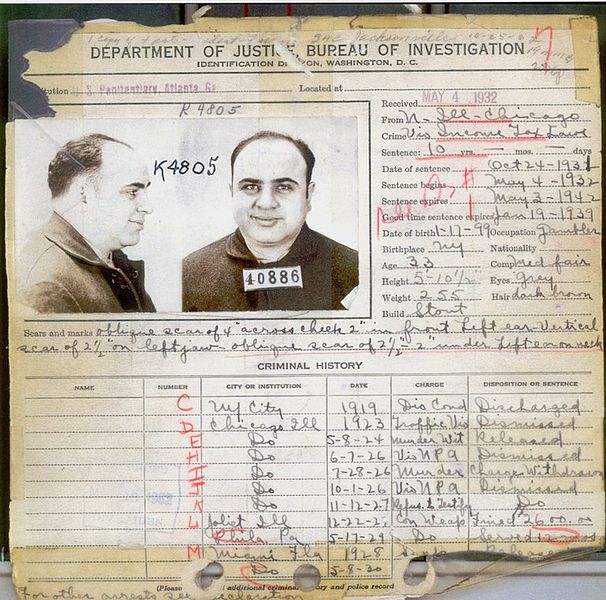

One day while working at the Harvard Inn, Capone saw a man and woman sitting at a table. After his initial advances were ignored, Capone went up to the good-looking woman and whispered in her ear, “Honey, you have a nice [butt] and I mean that as a compliment.” The man with her was her brother, Frank Gallucio. Defending his sister’s honor, Gallucio punched Capone. However, Capone didn’t let it end there; he decided to fight back. Gallucio then took out a knife and slashed at Capone’s face, managing to cut Capone’s left cheek three times (one of which cut Capone from ear to mouth). The scars left from this attack led to Capone’s nickname of “Scarface,” a name he personally hated. When photographed, Capone hid the scarred left side of his face, saying that the injuries were war wounds.

Capone’s crime gang raked in as much as $100 million annually.

At about 20 years of age, Capone left New York for Chicago at the invitation of Johnny Torrio, who was imported by crime boss James “Big Jim” Colosimo as an enforcer. In January 1925, Capone was ambushed, leaving him shaken but unhurt. Twelve days later, Torrio was returning from a shopping trip when he was shot several times. After recovering, Torrio effectively resigned and handed control to Capone, age 26, who became the new boss of an organization that took in illegal breweries and a transportation network that reached to Canada, with political and law-enforcement protection.

Capone expanded “the outfit,” as he referred to his underworld organization, and went on to become one of America’s leading mobsters. By some estimates, his crime syndicate pulled in around $100 million a year, the largest portion from bootlegging, followed by gambling, prostitution, racketeering and other illicit activities. A flashy dresser who liked chatting with reporters and became an international celebrity, Capone didn’t apologize for the way he made his living. He claimed to be doing a “public service” for Chicagoans, stating: “Ninety percent of the people of Cook County drink and gamble and my offense has been to furnish them with those amusements.”

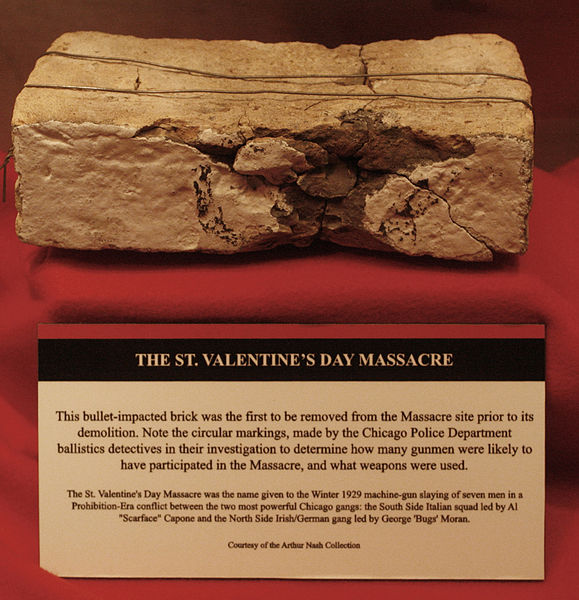

He was never charged in connection with the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

On the morning of February 14, 1929, seven men affiliated with the George “Bugs” Moran gang were shot to death while lined up against a wall inside a garage in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood. The victims included five of Moran’s criminal associates along with a mechanic who worked for him and an optometrist who hung around the group; Moran himself wasn’t there.

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre became a national media event immortalizing Capone as the most ruthless, feared, smartest and elegant of gangland bosses. Even while powerful forces were amassing against him, Capone indulged in one last bloody act of revenge — the killing of two Sicilian colleagues who he believed had betrayed him. Capone invited his victims to a sumptuous banquet where he brutally pulverized them with a baseball bat. Capone had observed the old tradition of wining and dining traitors before executing them. Capone was never charged in the case, which went unsolved.

Eliot Ness’s role in Capone’s downfall was exaggerated.

Thanks to federal agent Ness’s best-selling memoir “The Untouchables,” which spawned a TV series and movie, he has been credited as the man who took down Capone. In fact, much of the memoir was embellished by its co-author, Oscar Fraley. As a Prohibition agent, Ness and a small team of men raided illegal breweries and other places linked to Capone’s bootlegging operations around Chicago. Because the agents supposedly refused to accept bribes, they were dubbed the Untouchables by the press. Although Ness’s work helped lead to Capone’s indictment for Prohibition violations, the government instead focused on prosecuting the mobster for tax evasion and his 1931 conviction on those charges is what sent him to prison. Ness went on to serve as Cleveland’s director of public safety and made an unsuccessful bid for mayor there in 1947. His later years were marred by heavy drinking and he died at his home in Coudersport, Pennsylvania, in 1957, the year “The Untouchables” was published.

Capone was convicted of tax fraud but not murder.

On March 13, 1931, a federal grand jury met secretly on the government’s claim that in 1924 Al Capone had a tax liability of $32,488.81. The jury returned an indictment against Capone that was kept secret until the investigation was complete for the years 1925 to 1929. The grand jury later returned another indictment against Capone with 22 counts of tax evasion, totaling over $200,000. Capone and 68 members of his gang were charged with 5,000 separate violations of the Volstead Act. These income tax cases took precedence over the Prohibition violations.

After nine hours of discussion on October 17, 1931, the jury found Capone guilty of several counts of tax evasion. Judge Wilkerson sentenced him to eleven years, $50,000 in fines and court costs of another $30,000. Bail was denied. He was sentenced to 11 years behind bars and fined $50,000; it was the harshest sentence delivered for tax fraud up to that point.

He was among the earliest federal prisoners at Alcatraz.

Before arriving at Alcatraz, Capone had been a master at manipulating his environment at the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta. Despite strict convictions from the courts, Capone was always able to persuade his keepers into procuring his every whim, and often dictated his own privileges. It was said that he had convinced many guards to work for him, and his cell boasted expensive furnishings which included personal bedding along with many other amenities not extended to other inmates serving lesser crimes. His cell was carpeted, and also had a radio around which many of the guards would sit with Al conversing and listening to their favorite radio serials.

Two years later, in August 1934, he and a group of fellow inmates were sent by train to California then transported to the recently opened federal penitentiary on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. The maximum-security prison, intended to hold criminals who were especially violent or had other disciplinary problems, had received its first contingent of federal inmates earlier that August. Because Capone wasn’t a troublemaker while locked up in Atlanta, he likely was sent to Alcatraz as a way for the government to generate publicity for its tough, new facility.

Capone spent his final years out of the public spotlight.

Upon his arrival at Atlanta, the 250-pound (110 kg) Capone was officially diagnosed with syphilis and gonorrhea. He was also suffering from withdrawal symptoms from cocaine addiction, use of which had perforated his septum. While at Alcatraz, Capone, who’d been diagnosed with syphilis during a medical exam at the Atlanta penitentiary, started showing signs of the disease, including dementia. As his condition worsened, prison doctors treated him with malaria injections in the hope that the fevers caused by malaria would wipe out syphilis. Instead, the treatment nearly proved fatal for Capone. In January 1939, he was released from Alcatraz and transferred to the Federal Correctional Institution at Terminal Island, near Los Angeles, to serve his one-year misdemeanor sentence.

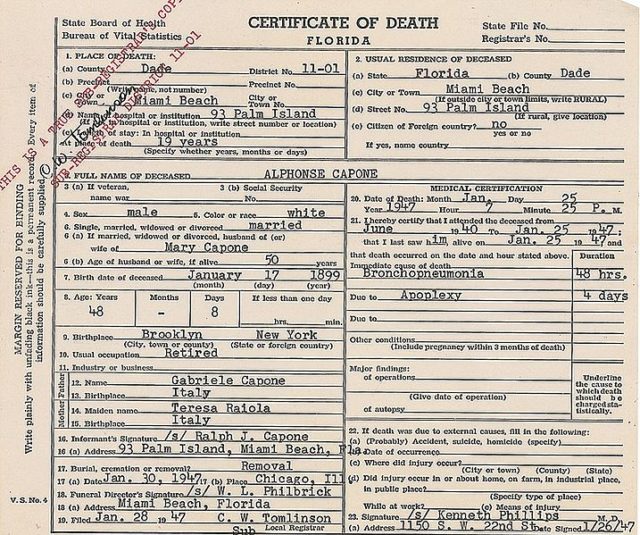

Capone was released from prison in November 1939 then underwent several months of treatment for syphilis at a Baltimore hospital. Afterward, the famous gangster spent much of his time out of the public spotlight, fishing and playing cards at the Palm Island, Florida, mansion he’d owned since 1928. In the 1940s, he became one of the first civilians to receive penicillin for syphilis, although it was too late to cure him. In January 1947, the 48-year-old Capone suffered a stroke then came down with pneumonia; he died at his Florida home on January 25. Capone was buried at Chicago’s Mount Olivet Cemetery, near the graves of his father and one of his brothers. In 1950, the Capone family had the remains of the three men moved to Mount Carmel Cemetery in Hillside, Illinois.