In late 1942, the tide started turning against Imperial Japan in the Pacific Theatre. After initial battle successes, the US and Australian armies crushed its forces in Papua New Guinea.

In an attempt to make the Americans back off, Japan resorted to – attacking the US mainland. The initial plan failed, but what grew out of it would stand as a testimony for generations to come.

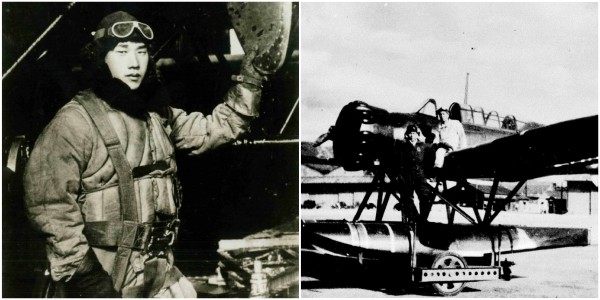

The year was 1932 when 21-years-old Nobuo Fujita joined the Imperial Japanese Navy. A year later he became a pilot, specialized in reconnaissance operations. Emperor Hirohito’s decision to enter WWII by attacking the American base at Pearl Harbor sent Fujita on a mission across Pacific.

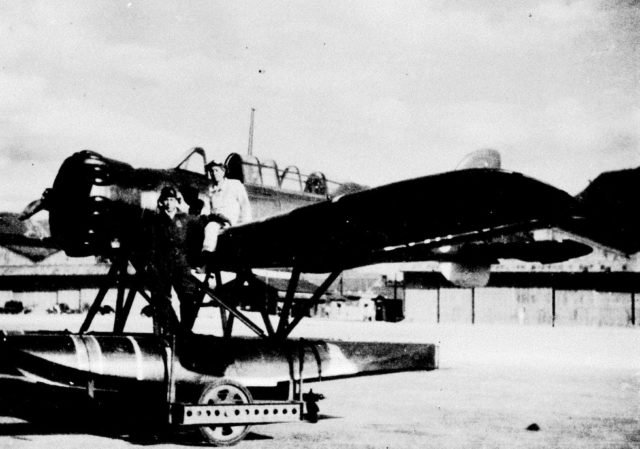

Launching of the attack saw him grounded at the long-range submarine aircraft carrier I-25. His Yokosuka E14Y “Glen” seaplane was out of order and Fujita failed to take part in the scouting mission prior to the attack. For the next several months, he participated in various missions in the South and Northwest Pacific.

By summer of 1942, Fujita was once again nearing the West Coast, witnessing his submarine’s attack on Fort Stevens, Oregon. News of his country’s combat failures pushed Fujita to put forward a plan of attacks on the US mainland.

Such attacks would instigate fear among the Americans, who would, in turn, withdraw some of their forces from the Pacific Theatre. That would offer Japan some critical breathing space.

Fujita’s plan didn’t seem as crazy to the increasingly desperate Japanese commanders. But the way they conducted it showed just how deranged they must have been.

The plan was to set fire to the woods surrounding the small logging town of Brookings, Oregon. The mission would further advance towards the Panama Canal. But practically the whole of it fell on Fujita’s shoulders.

In the early morning of September 9, 1942, I-25 catapulted Fujita’s “Glen” towards the coastline. His scouting plane carried two incendiary bombs. It flew over the town, causing some confusion among the locals. It dropped its load on Wheeler Ridge and Mount Emily.

The day before, heavy rain soaked the woods causing the ensuing fire to look nothing like planned. It seems like no one bothered to check the weather.

Several people spotted the smoke from the nearby lookouts. The fire was eventually put out by a total of two men. The following day, this story was reported as a minor incident in the American press, while their Japanese colleagues spoke of dread spreading across the US.

Three weeks later, Fujita was to repeat the show, this time with even less success. Instead of setting the West Coast aflame, Fujita’s submarine was forced to retreat. The first enemy bombing campaign of US mainland in history ended with a complete, absurd failure.

Back in Brookings

Two decades later, this former pilot was working in a wire-making factory. He was quiet and never spoke of his years on the front, where he lost his younger brother. He felt shame and remorse for having anything to do with Japan’s war efforts. Then one day he received a letter from Brookings.

A group of citizens invited him to fly back to Oregon and take part in a local festival in Brookings. Grateful for the invitation, but scared that he might be scorned by the locals, Fujita decided to bring something along – his 400-year-old katana. This sword accompanied his ancestors in numerous battles, and he had it by his side while he was flying over Brookings.

If all went well, he would offer it as a present to the citizens of Brookings. If not, he was resolute to deal with it in a traditional Japanese way – by committing ritual suicide.

To his surprise, the residents of Brookings greeted him like a celebrity. After all, he was a former enemy combatant who wanted to express his humility. The people loved it.

Grateful, Fujita responded by donating $1,000 to the Brookings library to purchase books about Japan so that those two countries would never again fight one another.

He returned to Brookings three more times, planted a tree on the place his first bomb fell and arranged for some high-school students to visit Japan.

Weeks before he succumbed to lung cancer in 1997, the town officials pronounced him an honorary citizen of Brookings. The news put the last smile on his face. He was at peace. Today, his katana hangs in the Brookings Library, as a reminder to the coming generations.