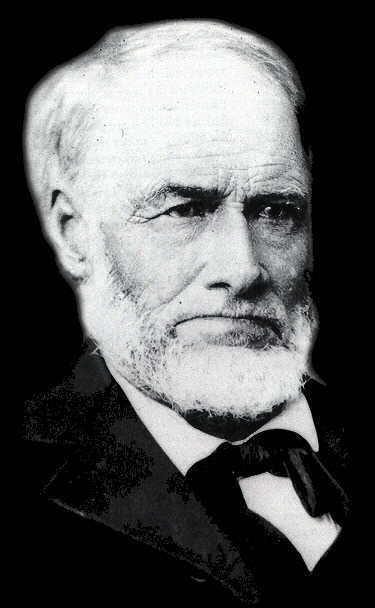

James Wilson Marshall, an American carpenter and sawmill operator, who reported the finding of gold at Coloma on the American River in California on January 24, 1848, the impetus for the California Gold Rush.

On the morning of January 24, 1848 Marshall was examining the channel below the mill when he noticed some shiny flecks in the channel bed. As later recounted by Marshall:

| “ | I picked up one or two pieces and examined them attentively; and having some general knowledge of minerals, I could not call to mind more than two which in any way resembled this, sulphuret of iron, very bright and brittle; and gold, bright, yet malleable. I then tried it between two rocks, and found that it could be beaten into a different shape, but not broken. I then collected four or five pieces and went up to Mr. Scott (who was working at the carpenter’s bench making the mill wheel) with the pieces in my hand and said, “I have found it.”“What is it?” inquired Scott. “Gold,” I answered. “Oh! no,” replied Scott, “That can’t be.” I said,–“I know it to be nothing else.” |

” |

The metal was confirmed to be gold after members of Marshall’s crew performed tests on the metal—boiling it in a lye solution and hammering it to test its malleability.

Marshall, still primarily concerned with the completion of the sawmill, permitted his crew to search for gold during their free time.

By the time Marshall returned to Sutter’s Fort, four days later, the war had ended and California was about to become an American possession. Marshall shared his discovery with Sutter, who performed further tests on the gold and told Marshall that it was “of the finest quality, of at least 23 karat [96% pure].”

News of the discovery soon reached around the world. The immediate impact for Marshall was negative. His sawmill failed when all the able-bodied men in the area abandoned everything to search for gold. Before long, arriving hordes of prospectors forced him off his land. Marshall soon left the area.

Marshall returned to Coloma in 1857 and found some success in the 1860s with a vineyard he started. That venture ended in failure towards the end of the decade, due mostly to higher taxes and increased competition. He returned to prospecting in the hopes of finding success.

He became a partner in a gold mine near Kelsey, California but the mine yielded nothing and left Marshall practically bankrupt. The California State Legislature awarded him a two-year pension in 1872 in recognition of his role in an important era in California history. It was renewed in 1874 and 1876 but lapsed in 1878. Marshall, penniless, eventually ended up in a small cabin.

Marshall died in Kelsey on August 10, 1885. In 1886, the members of the Native Sons of the Golden West, Placerville Parlor #9 felt that the “Discoverer of Gold” deserved a monument to mark his final resting place.

In May 1890, five years after Marshall’s death, Placerville Parlor #9 of the Native Sons of the Golden West successfully advocated the idea of a monument to the State Legislature, which appropriated a total of $9,000 for the construction of a monument and tomb which can be seen today, the first such monument erected in California.

A statue of Marshall stands on top of the monument, pointing to the spot where he made his discovery in 1848. The monument was rededicated October 8, 2010 by the Native Sons of the Golden West, Georgetown Parlor #91 in honor of the 200th Anniversary of James W. Marshall’s birth