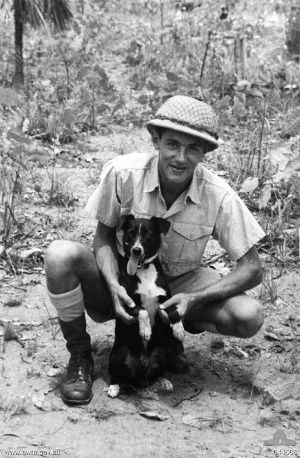

Japanese bombs started raining down on the capital city of Australia’s Northern Territory, Darwin, around 10 am on February 19, 1942 – just over two months after the Japanese bombing of America’s Pearl Harbor.

After the initial attack, which sunk eight ships and badly damaged 37 others, soldiers went looking for the injured among the rubble.

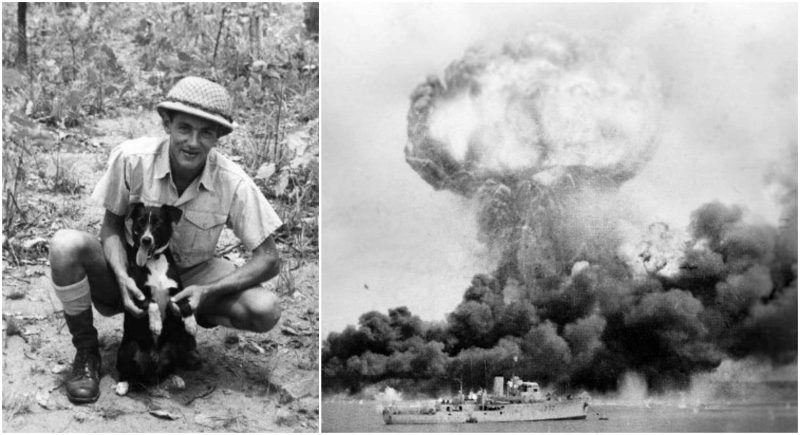

Under a destroyed mess hall, they found the smallest survivor of them all, a six-month-old male stray kelpie (an Australian sheep dog). He had a broken leg and was whimpering. Eventually, the injured pup ended up in the hands of Leading Aircraftman Percy Westcott.

He made it his duty to get this dog help. Westcott took the dog to the doctor, who said he couldn’t treat any “man” who didn’t have a name or serial number. So, Westcott named the kelpie “Gunner” and gave him the number 0000. Satisfied, the doctor put a cast on Gunner’s leg and set them on their way.

From that point forward, Gunner and Westcott were inseparable. At first, the dog was badly shaken after the bombing, but being only six months old he quickly responded to the men’s attention.

About a week later, Gunner first demonstrated his remarkable hearing skills. While the men were working on the airfield, Gunner became agitated and started to whine and jump.

Not long afterward, the sound of approaching airplane engines was heard by the airmen. A few minutes, later a wave of Japanese raiders appeared in the skies above Darwin and began bombing and strafing the town.

Two days later, Gunner began whimpering and jumping again and not long afterwards came another air attack. This set the pattern for the months that followed. Long before the sirens sounded, Gunner would get agitated and head for shelter.

Gunner’s hearing was so acute he was able to warn air force personnel of approaching Japanese aircraft up to 20 minutes before they arrived and before they showed up on the radar. Gunner never performed when he heard the allied planes taking off or landing; only when he heard enemy aircraft, as he could differentiate between the sounds of allied from enemy aircraft.

Gunner was so reliable that Wing Commander McFarlane gave approval for Westcott to sound a portable air raid siren whenever Gunner’s whining or jumping alerted him. Before long, there were a number of stray dogs roaming the base. McFarlane gave the order that all dogs be shot, with the exception of Gunner.

Gunner became such an important part of the air force that he slept under Westcott’s bunk, showered with the men in the shower block, sat with the men at the outdoor movie pictures, and went up with the pilots during practice take-off and landings. When Westcott was posted to Melbourne 18 months later, Gunner stayed in Darwin, looked after by the RAAF butcher. Gunner’s fate is undocumented.