Before the Columbian Exchange, there were no oranges in Florida, no bananas in Ecuador, no paprika in Hungary, no potatoes in Ireland, no coffee in Colombia, no pineapples in Hawaii, no rubber trees in Africa, no chili peppers in Thailand, no tomatoes in Italy, and no chocolate in Switzerland.

The Columbian Exchange refers to a period of cultural and biological exchanges between the New and Old Worlds. Exchanges of plants, animals, diseases and technology transformed European and Native American ways of life. Beginning after Columbus’ discovery in 1492, the exchange lasted throughout the years of expansion and discovery. The Columbian Exchange impacted the social and cultural makeup of both sides of the Atlantic. Advancements in agricultural production, evolution of warfare, increased mortality rates and education are a few examples of the effect of the Columbian Exchange on both Europeans and Native Americans.

The contact between the two areas circulated a wide variety of new crops and livestock, which supported increases in population in both hemispheres, although diseases initially caused precipitous declines in the numbers of indigenous peoples of the Americas. Traders returned to Europe with maize, potatoes, and tomatoes, which became very important crops in Europe by the 18th century. Similarly, Europeans introduced the manioc and peanut to tropical Asia and West Africa, where they flourished in soils that otherwise would not produce large yields.

The term was first used in 1972 by American historian Alfred W. Crosby in his environmental history book The Columbian Exchange. It was rapidly adopted by other historians and journalists and has since become widely known.

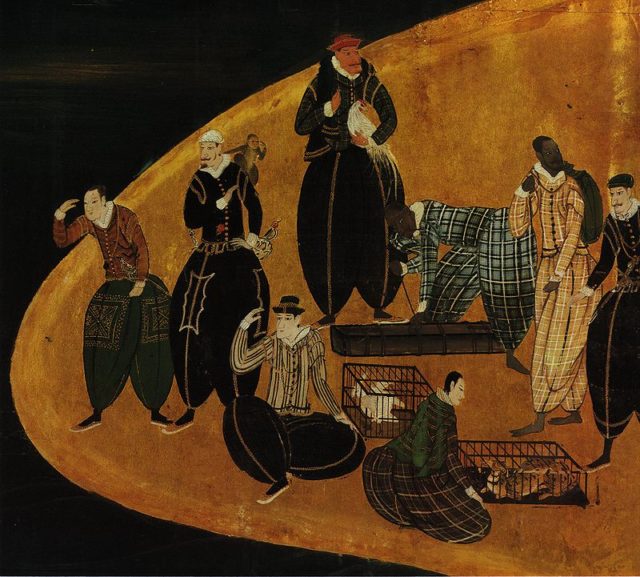

Before AD 1500, potatoes were not grown outside of South America. By the 1840s, Ireland was so dependent on the potato that the proximate cause of the Great Famine was a potato disease. Potatoes eventually became an important staple of the diet in much of Europe. Many European rulers, including Frederick the Great of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia, encouraged the cultivation of the potato. Maize and manioc, introduced by the Portuguese from South America in the 16th century, have replaced sorghum and millet as Africa’s most important food crops. 16th-century Spanish colonizers introduced new staple crops to Asia from the Americas, including maize and sweet potatoes, and thereby contributed to population growth in Asia.

Tomatoes, which came to Europe from the New World via Spain, were initially prized in Italy mainly for their ornamental value. From the 19th-century tomato sauces became typical of Neapolitan cooking and, ultimately, Italian food in general. Coffee (introduced in the Americas circa 1720) from Africa and the Middle East and sugar cane (introduced from South Asia) from the Spanish West Indies became the main export commodity crops of extensive Latin American plantations. Introduced to India by the Portuguese, chili and potatoes from South America have become an integral part of Indian cuisine.

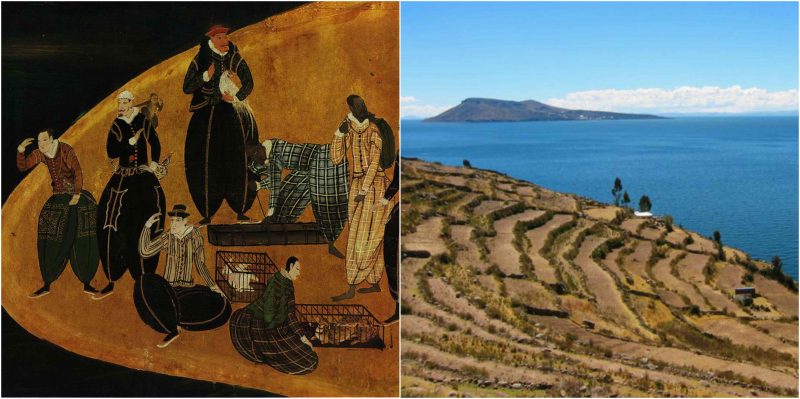

Initially, at least, the Columbian exchange of animals largely went through one route, from Europe to the New World, as the Eurasian regions had domesticated many more animals. Horses, donkeys, mules, pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, chickens, large dogs, cats and bees were rapidly adopted by native peoples for transport, food, and other uses. One of the first European exports to the Americas, the horse, changed the lives of many Native American tribes in the mountains. They shifted to a nomadic lifestyle, as opposed to agriculture, based on hunting bison on horseback and moved down to the Great Plains. The existing Plains tribes extended their territories with horses, and the animals were considered so valuable that horse herds became a measure of wealth.

Still, the effects of the introduction of European livestock on the environments and peoples of the New World were far from positive. In the Caribbean, the proliferation of European animals had large effects on native fauna and undergrowth and damaged conucos, plots managed by indigenous peoples for subsistence. The deadliest import from Europe to the New World was the plethora of diseases, brought by explorers, which devestated the native American population.