Hermits are most often associated with tales of solitary men devoted to God. Their image is largely shaped by the fact that their devotion leaves little or no space for human contact, not to mention basic hygiene.

The bearded loners living in caves while spending their time praying or studying the word of God always held a special place in the Christian world.

A touch of mystique was also considered part of the hermit’s life, as he was supposed to be closer to God than the rest of the flock. Even though the phenomenon originated in the Middle East, the birthplace of Christianity, it swept across Europe during the medieval period. The Catholic Church honored and protected the choice of the hermit.

Hermits lived in solitude in various places, including England. Until that is, King Henry VIII broke with the Roman Catholic church in the mid-16th century and went around destroying monasteries in order to suppress their influence.

This decline in spiritual life left only a memory of the rugged men who had rejected worldly pleasures so they could be closer to God.

With the development of Romanticism in the late 18th century, interest grew in religious mysticism and the idea that life is more than that which meets the eye and such topics were much discussed among the intellectual elite in England.

Literature of the time featured many eccentric characters, often described as hermits of various sorts, who were deeply involved in studying alchemy, science, religion, and philosophy. It wasn’t long before it was fashionable among the English upper class to “own” their very own hermit as an expression of their intellectual sophistication and romantic sentiment.

This fashion quickly captured the imagination of many noblemen and gentlemen, as well as ladies. Respectable households would have a so-called ornamental hermit living in the backyard. These people weren’t really hermits in the Biblical sense of the word, but rather actors or better yet, extras, in a “play” directed by the wealthy owner of the manor.

The hermits were expected to look the part, so they were forbidden to shave or cut their hair, fingernails, and toenails. And the reason for all of this?

Simple garden decoration. The role of these men was to serve as live-action statues on display for their employers, who were most often wealthy landowners.

The story of garden hermits would be largely forgotten today if it weren’t for Edith Sitwell, a British writer and essayist. Sitwell wrote an extensive book in 1933, titled English Eccentrics, summarizing all known accounts of aristocrats who decided to hire ornamental hermits.

According to Sitwell, the ornamental hermit was instructed to never leave the estate, nor to engage in conversation with guests (there were some exceptions), and to make his appearance at certain times of the day only, when he could be observed by his employer and his guests. His solitary lifestyle was perceived as a symbol of the passing of time and man’s own mortality–the original performance art!

In some other cases, the ornamental hermit served as a waiter for garden parties, engaged in some light agricultural work, or was instructed to talk to the curious visitors.

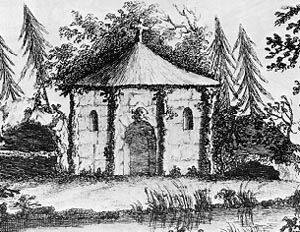

They were housed in underground chambers, caves, grottos, or cabins, equipped with different props which would add to their authenticity.

As for the contracts, they were usually very rigorous. The most famous arrangement between one such hermit and an aristocrat called Charles Hamilton illustrates the strict conditions under which a hermit was supposed to act:

(A hermit must) continue on the Hermitage seven years, where he shall be provided with a Bible, optical glasses, a mat for his feet, a hassock for his pillow, an hourglass for timepiece, water for his beverage, and food from the house. He must wear a camlet robe, and never, under any circumstances, must he cut his hair, beard, or nails, stray beyond the limits of Mr. Hamilton’s grounds, or exchange one word with the servant.

Unfortunately for Mr. Hamilton, the only known hermit that agreed upon these conditions lasted merely three weeks at his “workplace.” One day, he vanished from the estate and was later seen in a local pub, probably enjoying his freedom with a pint of beer.

Nevertheless, some did agree to act as garden gnomes, or in this case ornamental hermits. The reason for this was they were offered a fair amount of money. For example, Hamilton’s hermit was offered 700 pounds for his seven-year service, but the catch was that he would not receive the money before the given period had passed.

In case of violating the contract, the person acting as a hermit would receive no financial compensation whatsoever.

Even though it was the wealthy who most often searched for the hermits, some people were looking for sponsors in this particular line of work. One young man offered such services in his quest for solitude, isolation, and wisdom:

A young man, who wishes to retire from the world and live as a hermit, in some convenient spot in England, is willing to engage with any nobleman or gentleman who may be desirous of having one. Any letter addressed to S. Laurence (post paid), to be left at Mr. Otton’s No. 6 Coleman Lane, Plymouth, mentioning what gratuity will be given, and all other particulars will be duly attended.

This advertisement was published in the January 11, 1810 edition of the Courier, but whether or not the young man managed to find his dream job remains unknown.

The live ornamental hermit was soon replaced by ceramic statues of garden gnomes, which can be seen in some gardens to this day. The garden gnomes were mostly imported to England from Germany during the mid 19th century when the ridiculous ornamental hermits became largely extinct.