This time, gratitude goes to Jeannette Rankin who was the first woman to serve in the U.S. Congress. She helped pass the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote, and was a committed pacifist. Each of Rankin’s Congressional terms coincided with the beginning of U.S. military intervention in each of the World Wars. She was one of 50 House members (total of 56 in both chambers) who opposed the war declaration of 1917, and the only member of Congress to vote against declaring war on Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Rankin graduated from the University of Montana in 1902. After trying elementary school teaching and other occupations, she studied social work at the New York School of Philanthropy but found this profession also insufficiently rewarding. In 1910 she entered the University of Washington, where she joined the state suffrage organization. For the next four years, she traveled back and forth across the continent, speaking and lobbying for women’s right to vote. She was the driving force behind the organization that secured an unrestricted voting franchise for women in the state of Montana in 1914.

Two years later, Rankin was elected to Congress on the Republican ticket. Soon after taking her seat she cast an anguished vote against the declaration of war on Germany, stating, “I want to stand by my country, but I cannot vote for war.” During her term, she supported measures to protect female workers, mothers, and children, and efforts to abolish prostitution near army camps.

She voted for Prohibition and against the Espionage Act of 1917 and sought to end a strike in a copper field owned by the Anaconda company, the dominant political and economic power in Montana, by having the federal government nationalize the mine.

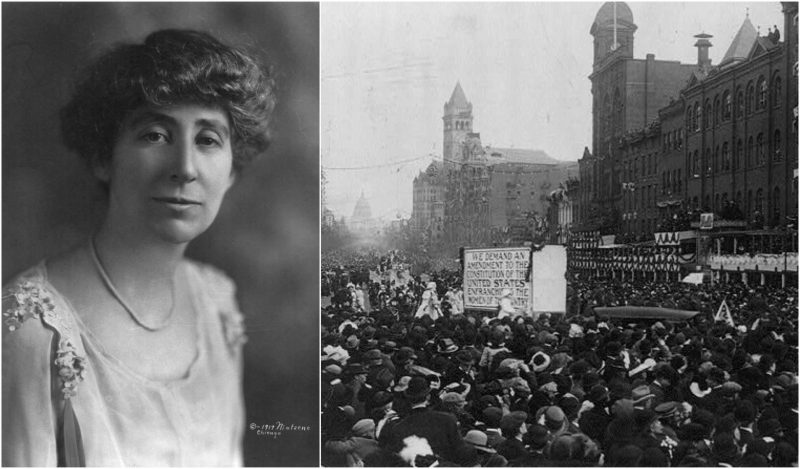

By 1918, women had been granted some form of voting rights in about forty states, but Rankin became a driving force in the movement for unrestricted universal enfranchisement. In January 1918 she opened congressional debate on a Constitutional amendment granting universal suffrage to women. The resolution passed in the House and was defeated by the Senate, but in 1919 a similar resolution passed both chambers.

After ratification by three-fourths of the states, it became the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Her affirmative vote on the original House resolution made Rankin, as she later noted, “… the only woman who ever voted to give women the right to vote.”

Rankin won election to the House once again in 1940, at the age of 60, defeating incumbent Jacob Thorkelson, an outspoken antisemite, in the July primary, and former Representative Jerry J. O’Connell in the general election. She was appointed to the Committee on Public Lands and the Committee on Insular Affairs. While members of Congress — and their constituents — had been debating the question of U.S. intervention in World War II for months, the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, galvanized the country and silenced virtually all opposition. On December 8, Rankin was the only member of either house of Congress to vote against the declaration of war on Japan.

Leaving office in 1943, Jeannette Rankin spent much of her time traveling. She was especially drawn to India because of Gandhi’s teachings on nonviolent protest. She also continued to work to further her pacifist beliefs, speaking out against U.S. military actions in Korea and Vietnam. She died on May 18, 1973, in Carmel, California, but was said to have been considering a third run for a House seat that year to protest the Vietnam War. This groundbreaking politician was the only legislator to vote against both world wars, reflecting her deep commitment to pacifism. She is also remembered for her tireless efforts on behalf of women’s suffrage.