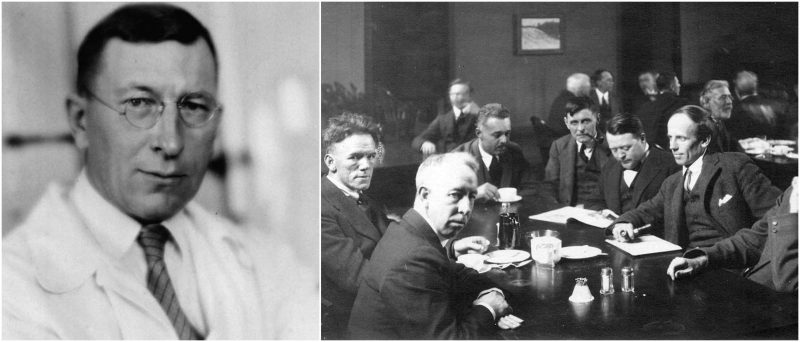

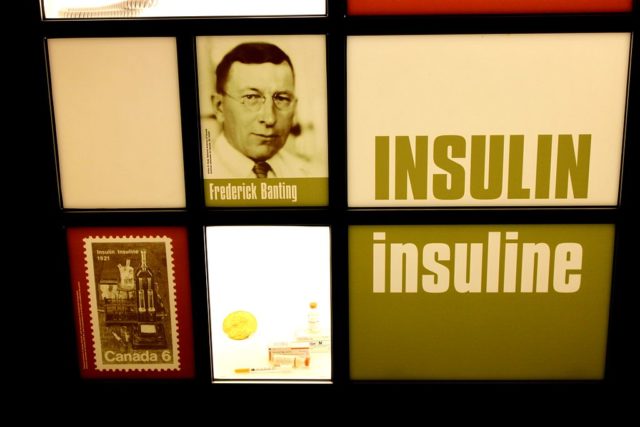

In 1923, Frederick Banting and John Macleod received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for their discovery of insulin. Banting shared the award money with his colleague, Dr. Charles Best. As of September 2011, Banting, who received the Nobel Prize at age 32, remains the youngest Nobel laureate in the area of Physiology/Medicine. The Canadian government gave him a lifetime annuity to work on his research. In 1934 he was knighted by King George V.

But his life wasn’t only about the insulin. After high school, he went to the University of Toronto to study divinity, but soon transferred to the study of medicine. In 1916 he took his M.B. degree and at once joined the Canadian Army Medical Corps, serving in France during the First World War. In 1918 he was wounded at the battle of Cambrai, and despite his injuries, he helped other wounded men for sixteen hours until another doctor told him to stop. In 1919 he was awarded the Military Cross for heroism under fire.

After the war, Banting returned to Canada to complete his surgical training. He was unable to gain a place among the hospital staff, and so he continued his general practice while teaching orthopedics and anthropology part-time at the University of Western Ontario. From 1921 to 1922, he lectured in pharmacology at the University of Toronto. He received his M.D. degree in 1922 and was also awarded a gold medal.

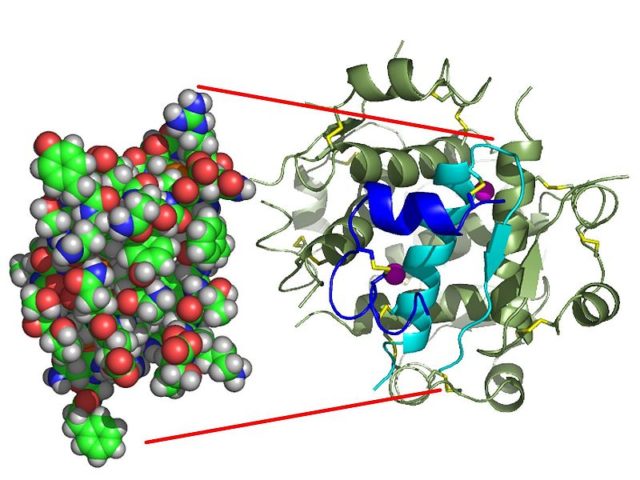

An article he read about the pancreas piqued Banting’s interest in diabetes. Banting had to give a talk on the pancreas to one of his classes at Western University on November 1, 1920, and he was, therefore, reading reports that other scientists had written. Research by Naunyn, Minkowski, Opie, Schafer, and others suggested that diabetes resulted from a lack of a protein hormone secreted by the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. Schafer had named this putative hormone “insulin”.

Insulin was thought to control the metabolism of sugar; its lack led to an increase of sugar in the blood which was then excreted in urine. Attempts to extract insulin from ground-up pancreas cells were unsuccessful, likely because of the destruction of the insulin by the proteolysis enzyme of the pancreas. The challenge was to find a way to extract insulin from the pancreas prior to it being destroyed.

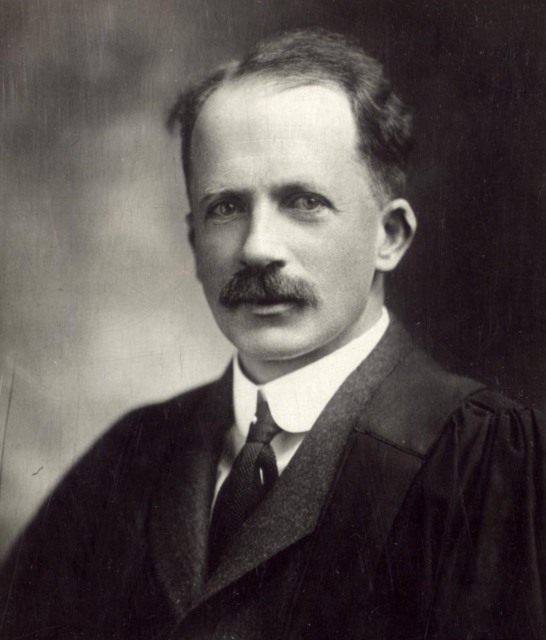

Banting discussed his approach for extracting the insulin from the islets of Langerhans with J. J. R. Macleod, Professor of Physiology at the University of Toronto. Macleod provided experimental facilities and the assistance of one of his students, Dr. Charles Best. Banting and Best, with the assistance of biochemist James Collip, began the production of insulin by this means.

Banting and Macleod were jointly awarded the 1923 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Banting flew into a rage that he would share the Prize with Macleod, whom he felt had not contributed enough to deserve the Prize. He eventually decided to split his half of the Prize money with Best.

At this point, large pharmaceutical companies offered the Banting huge sums of money for the patent to insulin. They proposed an insulin clinic with Banting in charge, and would make the medicine available to all who could pay for it. Banting, however, said that insulin was his gift to mankind, and it would be available to everyone who needed it rather than a commodity for anyone’s profit.

In 1923, Banting was just 31 years old when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Considered one the world’s most influential medical experts, Banting sought refuge from his newfound professional pressures through his pursuit of painting.

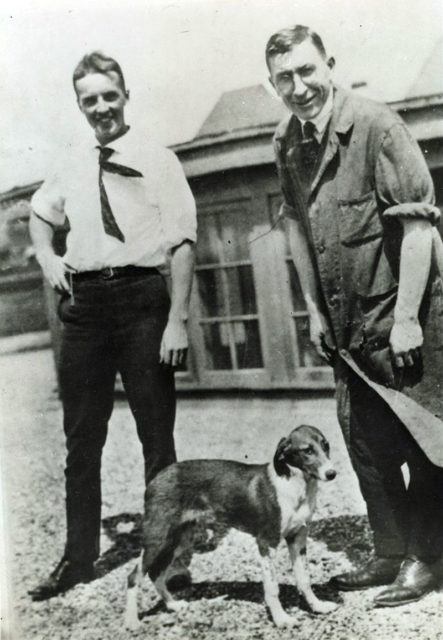

He eventually formed a close bond with Group of Seven painter A.Y. Jackson, and the two traveled much of Canada together, painting the Canadian Rockies and Northern landscape among other iconic Canadian locales. Banting’s fame and the quality of his work would lead to him being regarded as one of Canada’s more noteworthy amateur artists, and to this day his works are quite collectible in many art circles.

By the time the Second World War broke out, Banting was long-known as the discoverer of insulin, but his life-saving research wasn’t finished yet. In 1938, Banting began working for the National Research Council in an effort to fix what he viewed as a potentially critical gap in Allied scientific knowledge: aviation medicine.

Specifically, Banting’s work helped contribute to the invention of the G-suit, a special outfit worn by pilots which prevents blood from pooling in the lower part of their body, causing them to black out. In 1941, Banting — who was no stranger to risking life and limb for country — made the decision to fly to Great Britain to ensure the safe transfer of secret research considered invaluable to Allied war efforts.

Shortly after departing from Gander, Newfoundland, both engines of Banting’s plane failed, and the aircraft crashed on Newfoundland’s remote Seven Mile Pond. Despite initially surviving the crash, Banting was mortally wounded, and on February 21, 1941, he died along with two of the plane’s crew members. Search planes would eventually find the doomed flight’s lone survivor, the plane’s captain.

Originally purchased by the Canadian Diabetes Association in 1981, Banting House National Historic Site of Canada has grown to become one of London, Ontario’s most important national and international tourist attractions. The house — where a young Banting started his fledgling medical practice in 1920 — has since been converted into a full-featured National Historic Site of Canada, and offers an expansive gallery of Banting artwork, an array of historical artifacts, and a fully restored bedroom that captures the exact moment in time when Banting first conceived the idea for insulin. Visitors from across the world leave letters thanking Banting for his life-changing discovery, and his bedroom has since been turned into a veritable shrine.