It was once as the prosperous Bronze Age city and a center of art and trade, but the ancient settlement of Haft Tappeh in modern-day Iran could be hiding a murky secret. Archaeologists excavating the relics of the 4,000-year-old metropolis, which was a main center of the Elamite realm, have found a vast grave comprising of hundreds of skeletons.

They believe that the people found in the grave, which contains children that were stacked on top of each other behind a wall, were the victims of a barbarous massacre that occurred around 3,400 years ago.

The killings seem to coincide with a time when new construction work in the city stopped, and the community began to decline.

Historians are puzzled as to why the urbanized Haft Tappeh seems to have stagnated so suddenly after several hundred years of prosperity and growth.

What Was Haft Tappeh?

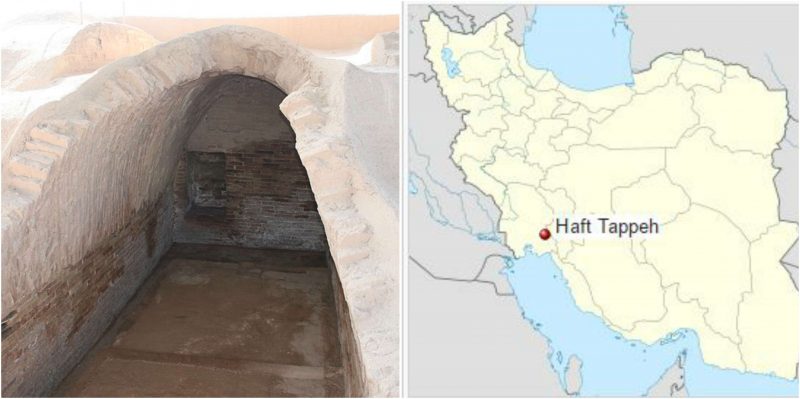

Haft Tappeh is believed to be the location of an ancient city that dates all the way back to 1500BC. From time to time known as Kabnak, it is assumed to have been a significant political center all through the time in power of the Elamite king Tepti-Ahar. The Elamites were a pre-Iranic development state located in the far west of current Iran. It first appeared in about 2700BC, before vanishing in 539BC.

It is believed that Tepti-Ahar moved the capital of his kingdom to Haft Tappeh. A huge tomb was constructed in the city to house the king and his family after he perished.

Skeleton remains discovered in the tomb are assumed to belong to the Royal family, but their identities have yet not been established.

The finding suggests that the metropolis’s populace might have fallen prey to a ruthless war, possibly as opposing clutches fought for control in the streets. The king of the Elamite Empire at the period, Tepti-ahar, is believed to have been the last in the reigning Kidinuid Empire, and the skeletons might have been victims of the strife that shadowed his demise as opposing families clashed for control.

An archaeologist who led the excavation said 149 skulls had been found so far, and the unexcavated portion of the trench could possibly contain an additionally 100 to 150 skeletons. Several of the skulls appeared to belong to children. Alongside the human remains, they found pottery vessels from the Middle Elamite era, as well as some date kernels. Even though there is no suggestion of a normal burial, it appears that people tried to gift the deceased what little food they could spare as grave goods. The huge number of dead support the theory that a massacre or epidemic had taken place, especially given the haphazard way the bodies were left – piled atop one another.

Archaeologists found the remnants of the city in the Khuzestan Region of southwest Iran in 1908, but couldn’t reach it until the 1970s. After these initial excavations, the site became inaccessible until 2007, when German archaeologists were able to return. The digging works have revealed a huge ancient temple, as well as a large royal tomb beneath it.

The temple seems to have been decorated with wall painting and bronze plates. Other very large structures have been found, including an ancient administrative center containing a number of clay tablets written in cuneiform script. Archeologists found evidence that many of these large structures had been abandoned between 1400BC and 1500BC, with the resources being salvaged and used to create modest houses.

A statement from the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz explained how the city grew very quickly; dozens of huge monuments and structures were erected in a very short space of time and the city expanded to cover an area of about 250 hectares, it flourishing for about 100 years as a center of trade and politics, and then mysteriously entered a period of great stagnation and decline at the end of the 14th century BC.