Since 2011 a team of archeologists, led by Dr. Michael Walker, has been excavating a cave in the southeast of Spain. They have found burnt rocks and charred bone, dating back more than 800,000 years. This is the earliest evidence found of fire-making in Europe, and researchers say that the remains are evidence that human ancestors may have regularly used controlled fires for cooking as far back as one million years ago.

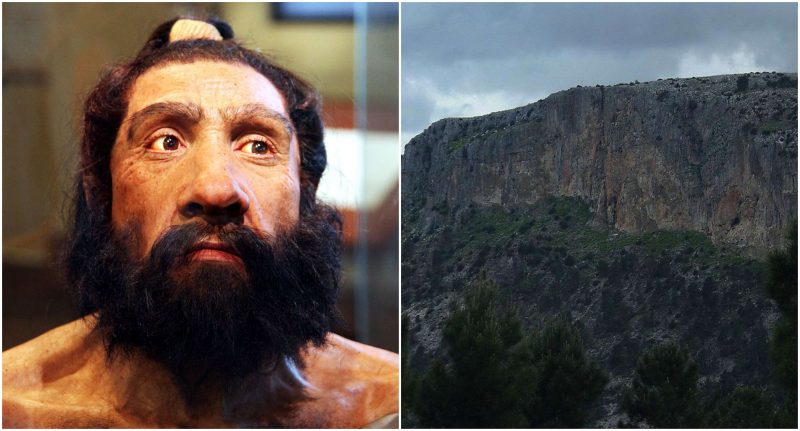

The site is located at Cueva Negra del Estrecho del Río Quípar, eighty kilometers west of Murcia, and has been a location of interest for many years. The site, called the “Black Cave,” is actually a rocky shelter under a cliff, located 780 meters above sea level.

Dr. Walker, an Emeritus professor at Murcia, explained the importance of this find: “Of enormous significance here, from the standpoint of human evolution, is that it implies early humans a million years ago had lost the fear of fire that causes other animals to flee before it.” He elaborated that “It implies an evolution of human cognitive awareness far beyond that of the great apes of the African jungles, or even the two-legged Australopithecine hominids of between four and two million years ago in Africa.”

The dating of the site has, naturally, not been exact. Rather, experts have taken what evidence they have found and combined that with the dating analysis previously done. Researchers remain skeptical of that date due to difficulty in discerning clear layers of sediment and the original position of fragments. According to the Science News, the team was able to estimate a date for the charred remains based on the surrounding layers of rock, which show evidence of a reversal of the Earth’s magnetic field some 780,000 years ago. Previous analysis of tools and remains — Neanderthal and animal alike — found at the site has to around 650,000 years ago during the Pleistocene period.

Speaking of sediment, archeologists also found hydroxyapatite — the calcium phosphate compound which makes up bone — which analysis showed had been heated at temperatures of 400˚ to 600˚C (752˚ to 1,112˚F). This means that the bones were clearly burned in a fire, said the team.

While archeologists have been arguing about the date of the fire in the Black Cave, undisputed evidence had been found in South Africa in 2012. This evidence also takes the shape of charred bones, and they date back to one million years ago. Regardless of the date, the Cueva Negra evidence would support theories that fire-making was discovered first in Africa, before being taken to the Middle East and Europe. The team, writing in the journal Antiquity, explained. “The results provide new insight into Early Paleolithic use of fire and its significance for human evolution.”

Scientists have long theorized the influence of fire on the development of the modern human. One such theory is that the discovery of fire — specifically its application in cooking — was one of the main driving events in human evolution and that led to the rise of the physical characteristics of the modern human, Homo Sapiens.

One such theory, proposed by British primatologist Richard Wrangham, suggests that the early mastery of fire paved the way for the path to modern humans. Their intestines shrank over time because the cooked food was easier to digest, and thus, the energy was rerouted to be used by their expanding brains.

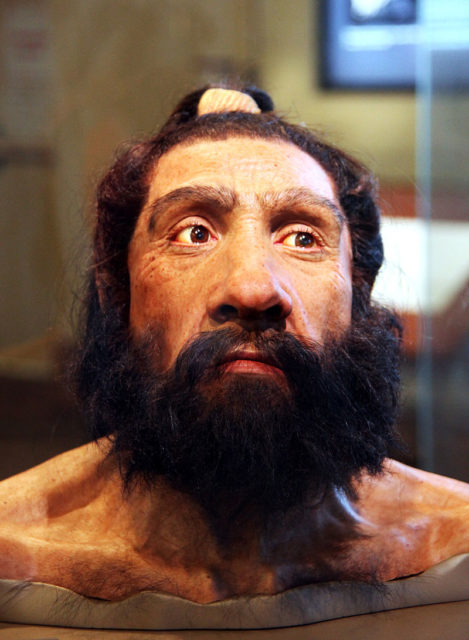

The Neanderthals were part of the Homo group, but they disappeared around 40,000 years ago. For a long time, scientists believed that Neanderthals were dimwitted and were driven to extinction by their lack of cranial capacity.

That assumption, however, has been revised due to recent archeological evidence, dating back to 200,000, and now, most scientists believe that Neanderthals “disappeared” because of interbreeding and assimilation with the early modern human ancestors.

In reality, Neanderthals were quite sophisticated. They knew how to make fire. They could make stone tools and even made jewelry. For example, eight talons taken from a white-tailed eagle found at a site in Krapina in Croatia were used to create a necklace or bracelet 130,000 years ago.