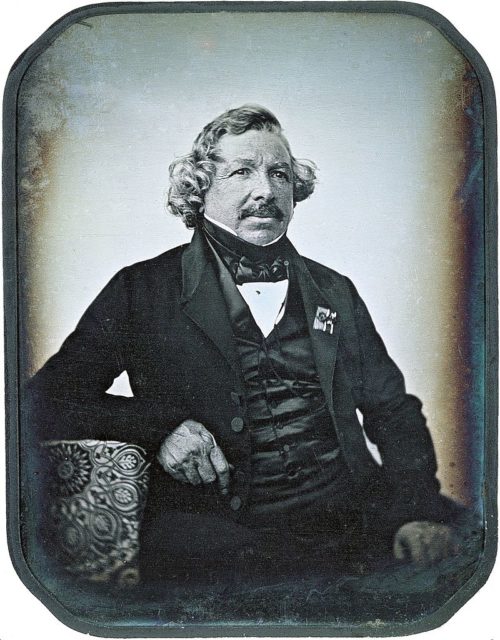

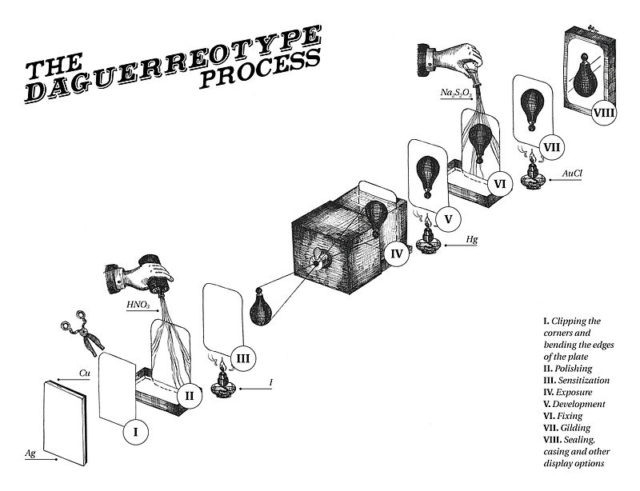

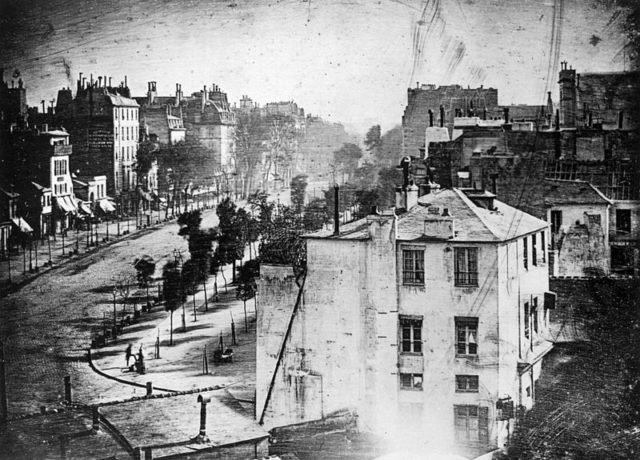

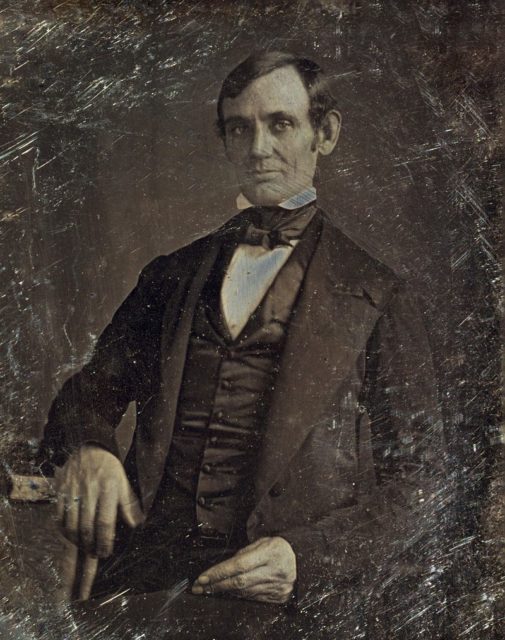

The daguerreotype was the first commercially successful photographic process in the history of photography, and it was introduced worldwide in 1839. Named after the inventor, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, each daguerreotype is a unique image on a silvered copper plate.

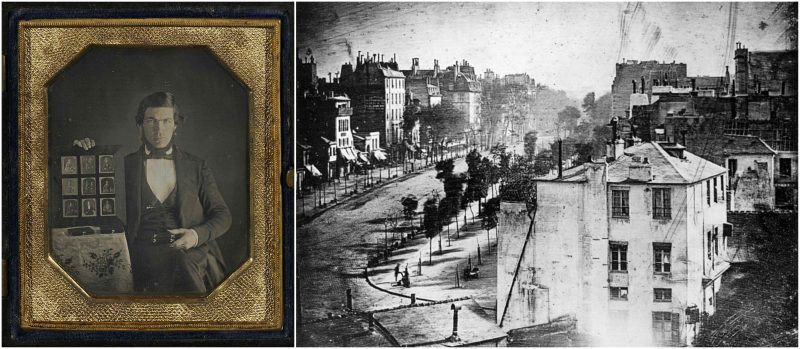

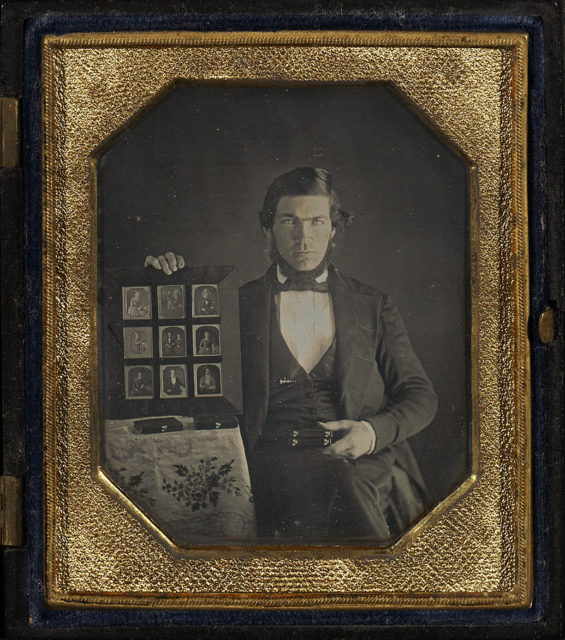

In contrast to photographic paper, a daguerreotype is not flexible and is rather heavy. The daguerreotype is accurate, detailed and sharp. It has a mirror-like surface and is very fragile. Since the metal plate is extremely vulnerable, most daguerreotypes are presented in a special housing. Different types of casings existed: an open model, a folding case, jewelry, and many others.

Unbeknownst to either inventor, Daguerre’s developmental work in the mid-1830s coincided with photographic experiments being conducted by Henry Fox Talbot in England. Talbot had succeeded in producing a “sensitive paper” impregnated with silver chloride and capturing small camera images on it in the summer of 1835, though he did not publicly reveal this until January 1839.

Talbot was unaware that Daguerre’s late partner Niépce had obtained similar small camera images on silver-chloride-coated paper nearly twenty years earlier.

Niépce could find no way to keep them from darkening all over when exposed to light for viewing and had therefore turned away from silver salts to experiment with other substances such as bitumen. Talbot chemically stabilized his images to withstand subsequent inspection in daylight by treating them with a strong solution of common salt.

When the first reports of the French Academy of Sciences announcement of Daguerre’s invention reached Talbot, with no details about the exact nature of the images or the process itself, he assumed that methods similar to his own must have been used, and promptly wrote an open letter to the Academy claiming priority of invention. Although it soon became apparent that Daguerre’s process was very unlike his own, Talbot had been stimulated to resume his long-discontinued photographic experiments.

The “developed out” daguerreotype process only required an exposure sufficient to create a very faint or completely invisible latent image which was then chemically developed to full visibility. Talbot’s earlier “sensitive paper” (now known as “salted paper”) process was a “printed out” process that required prolonged exposure in the camera until the image was fully formed. However, his later calotype paper negative process (also known as Talbotype), introduced in 1841, also used latent image development, significantly reducing the exposure needed, and making it competitive with the daguerreotype.

Daguerre’s agent Miles Berry applied for a British patent just days before France declared the invention “free to the world.” Great Britain was thereby uniquely denied France’s gift and became the only country where the payment of license fees was required. This had the effect of inhibiting the spread of the process there, to the eventual advantage of competing processes which were subsequently introduced.

Antoine Claudet was one of the few people legally licensed to make daguerreotypes in Britain. Daguerre’s pension was relatively modest — barely enough to support a middle-class existence — and apparently this British “irregularity” was allowed to pass without adverse consequences or much comment outside of the UK.