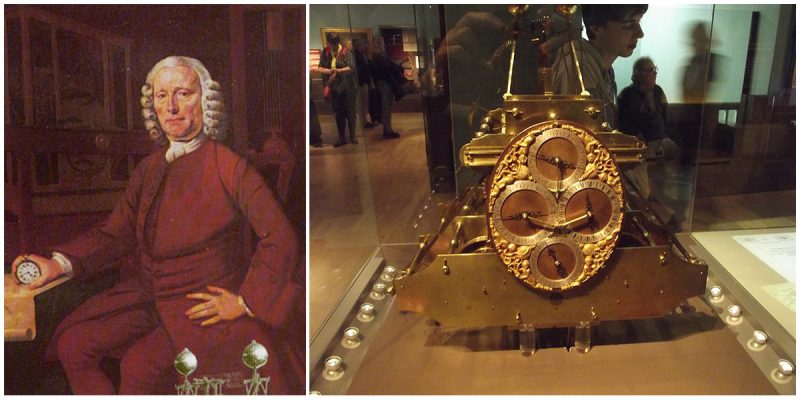

Born in 1693 in Foulby, near Wakefield in Yorkshire, the self-educated English carpenter and clockmaker John Harrison was the inventor of the marine chronometer – a long sought after device for solving the problem of calculating longitude while at sea.

He built his first longcase clock in 1713, at the age of 20. The mechanism was made entirely of wood, which was a natural choice of material for a joiner.

Three Harrison’s wooden clocks have survived: the first, made in 1713, has been in the Science Museum in London since 2015. The second, made in 1715, is also at the Science museum and the third, made in 1717, is at Nostell Priory in Yorkshire.

John Harrison is very known for the invention of the first marine chronometer.

It took thirty-one years of persistent experimentation and testing to create the chronometer, and it revolutionized naval navigation and enabling the Age of Discovery and Colonialism to accelerate.

Harrison wanted to solve the problem of determining longitude because, after a long voyage on sea, cumulative errors in dead reckoning frequently led to shipwrecks and a great loss of life.

Avoiding such disasters became Harrison’s great goal in an era when trade and navigation were increasing dramatically around the world.

To solve the problem, Harrison would have to devise a portable clock which kept time to the same accuracy as these precision regulators.

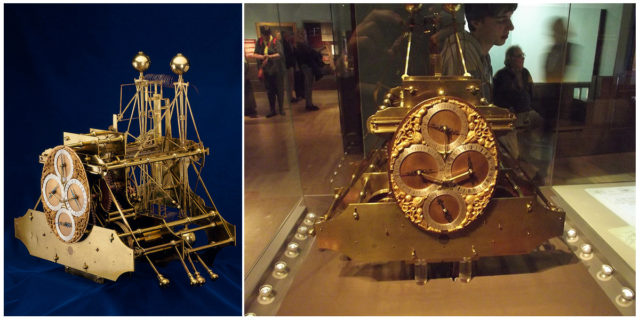

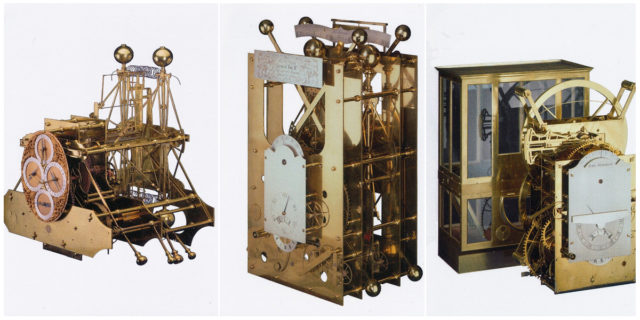

He worked on three portable clocks, H1, H2 and H3, filled with features of his great ingenuity.

It took Harrison five years to built his first Sea Clock (H1), which was the first proposal that the Board considered to be worthy of a sea trial.

Harrison moved on to develop H2, a more compact and rugged version, but he suddenly abandoned all work on this second machine when he discovered a serious design flaw in the concept of the bar balances.

Then he proceeded to work on H3 and he spent seventeen years working on this third sea clock, but despite every effort, it did not perform exactly as he would have wished.

He started to design the H4 which was completely different from the other three sea clocks. This clock not only met the requirements for Parliament’s top prize in a trial but greatly exceeded them.

Harrison’s son William set sail for the West Indies with H4 and he arrived in Jamaica on 19 January 1762, where the watch was found to be only 5.1 seconds slow.

After making his H5 sea clock, Harrison received a lot of money for his work on chronometers but never won an official award. He had spent his entire life solving a tough problem, but in the end, his invention significantly benefited the entire world and particularly the field of maritime navigation.