While Private J. Robert Conroy was training for combat in the fields of Yale University in 1917, he found a pit bull puppy with a short tail. He named this puppy “Stubby”, and soon the dog became the mascot of the 102nd Infantry, 26th Yankee Division.

From a homeless dog, Stubby become a true war hero. He saved lives, learned the bugle calls, the drills, and even a modified dog salute as he put his right paw on his right eyebrow when a salute was executed by his fellow soldiers.

Conroy brought Stubby back to the camp, leaving food out for him and letting him slip in the barracks and although pets weren’t allowed, Stubby provided a boost for the soldier’s morale and was able to stay. While living with the soldiers, clever young Stubby trained as well. He became familiar with marching routines and learned the bugle calls.

In September 1917, just a few months after Stubby came into the camp the 102nd Infantry prepared to ship out. Conroy was now facing a very serious problem: How to take Stubby with him on the boat without being noticed? Dogs were not an uncommon sight during the war, but the United States Army didn’t employ many of them—they were used more often by the Europeans. Conroy eluded the ship guards by concealing Stubby in his Army-issue greatcoat. He then spirited the dog down to the hold and hid him in the ship’s coal bin.

At some point during the trip, Sergeant Stubby was discovered by the commanding officer, who was not at all pleased. Stubby perhaps felt that he was in trouble, so he saluted the commanding officer. He was so impressed that he decided to let him stay. This was probably one of the best decisions he made in his career.

In October 1917, one month after landing in France, the American Expeditionary Forces entered the Western Front. They took part in four major offensives and 17 engagements. They were fighting 210 days in total. Stubby was there every single day.

He stopped only when they did, and remained eager to go one more time through the fire, which he did with renewed charges for over a month. He jumped over bodies and stayed with the attack, ready to come to the service of a fallen friend. During this time, he learned a vital trade that began saving lives. That whistle. He heard the incoming artillery long before any human ear, and his warning bark sent men scrambling for cover before the shells landed.

Stubby was wounded at least once, coming away from a battle with shrapnel embedded in his chest and legs. He was rushed to the hospital and had to undergo surgery, but ended up making a full recovery. While he convalesced, he visited with soldiers in the hospital, boosting morale.

Not long after his leg healed and he returned to the trenches, Stubby was sprayed with mustard gas. He made a full recovery, but the encounter with the dangerous gas left Stubby sensitive to the smell. This came in very useful during a German gas attack a while later, which happened in the morning while most of the soldiers were asleep. When Stubby smelled the offending gas, he started barking and roused most of the soldiers before they inhaled too much, saving many lives.

Stubby had evidently learned to distinguish a khaki doughboy uniform from gray German military apparel and was able to identify enemy soldiers. He was also trained to differentiate between English and German speakers and learned to bark at the location of wounded English speaking soldiers until paramedics arrived to care for them. Stubby also was trained to whine when he heard incoming artillery shells, which alerted his fellow soldiers before human ears could pick up the sound.

In the Argonne, Stubby sniffed out a lost German soldier hiding in nearby bushes. The dog gave chase, eventually dragging the soldier back to the 102nd. To the victor go the spoils: from that moment, the Iron Cross medal that had been pinned to the German’s uniform adorned Stubby’s Army coat.

After the war, Stubby went back to the United States where he became an instant celebrity. He went to the White House twice, met three presidents, and in 1921 the American overall commander “Black Jack” Pershing personally pinned a one-of-a-kind “Dog Hero Gold Medal” on Stubby’s military jacket.

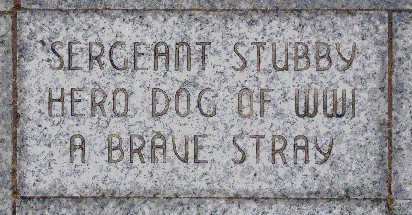

Sergeant Stubby, the American war hero dog, died in 1926, at the age of ten. He had done more than most people could ever hope to accomplish.