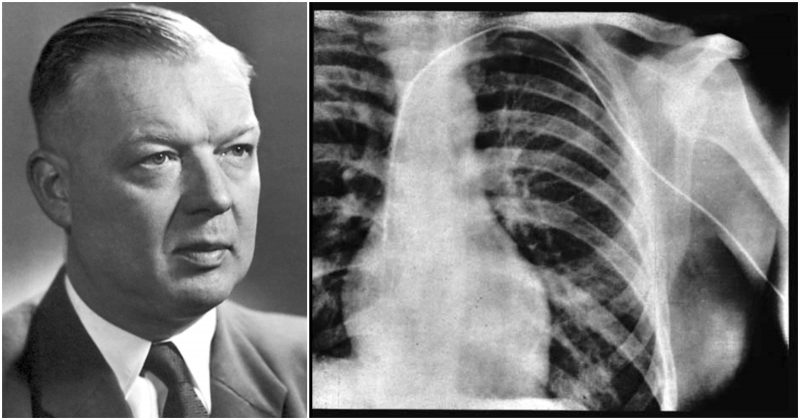

“It was very painful. I felt that I had planted an apple orchard and other men who had gathered the harvest stood at the wall, laughing at me,” said Dr. Werner Forssmann before he died.

In 1929, Werner Forssmann put himself under local anesthesia and inserted a catheter into a vein in his arm. Not knowing if the catheter might pierce a vein, he put his life at risk. Forssmann was nevertheless successful; he safely passed the catheter into his heart.

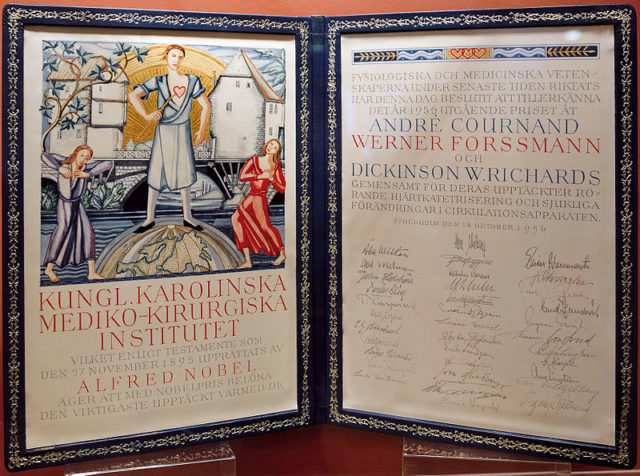

In 1956, he shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine (with Andre Cournand and Dickinson Richards) for developing a procedure that allowed for cardiac catheterization. The procedure allowed doctors to diagnose and treat heart conditions with much greater accuracy then before.

He went to study medicine at the University of Berlin. After passing his State Examination in 1929, he went to the University Medical Clinic for his clinical training where he worked under Professor Georg Klemperer, and he studied anatomy under Professor Rudolph Fick. For clinical instruction in surgery, he went, in 1929, to the August Victoria Home at Eberswalde near Berlin.

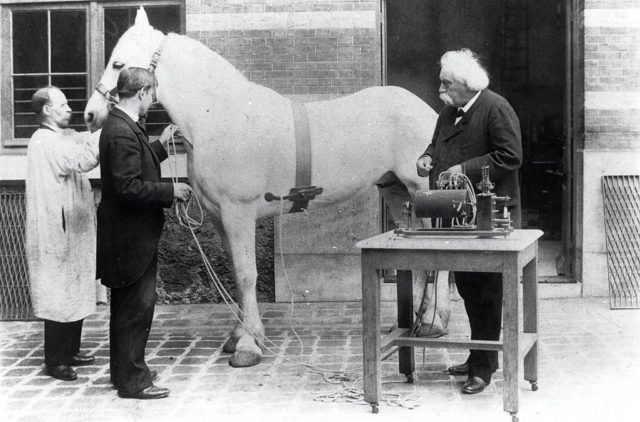

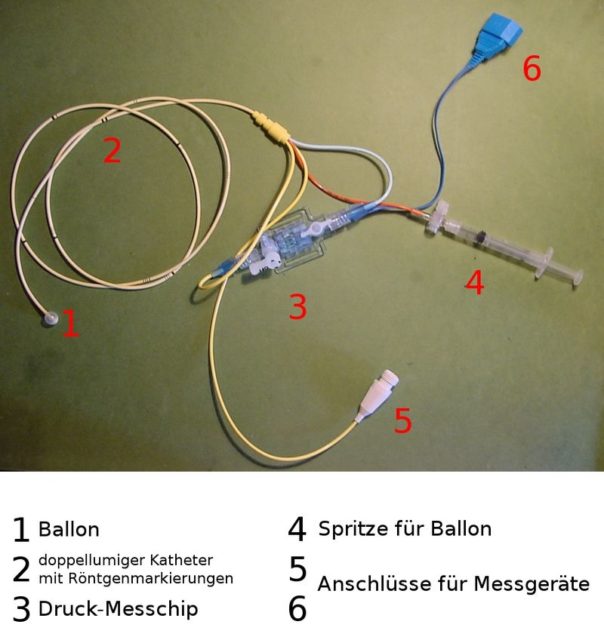

It was in Eberswalde where he performed the first human cardiac catheterization in 1929. Far from fantasy, Dr. Forssmann’s inspiration to perform what is now called cardiac catheterization came from a sketch in his physiology textbook depicting a long, thin tube being placed into a horse’s jugular vein and guided into the animal’s heart with balloon-assisted measurements of intracardiac pressures. Dr. Forssmann proposed to reach the heart of man — not through the jugular, but through the veins in the crease of the arm, which was more accessible.

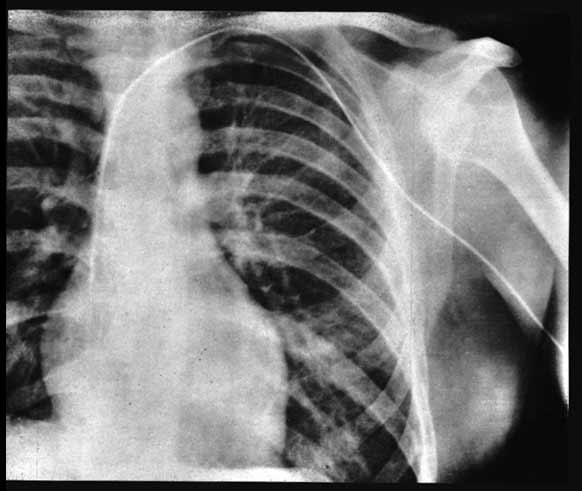

He didn’t get a permission by the clinic to do his experiment. Ignoring his department chief, Forssman persuaded the operating-room nurse in charge of the sterile supplies, Gerda Ditzen, to assist him. She agreed, but only on the promise that he would do it on her rather than on himself. However, Forssmann tricked her by strapping her to the operating table and pretending to locally anesthetize and cut her arm whilst actually doing it on himself. He anesthetized his own lower arm in the cubital region and inserted a uretic catheter into his antecubital vein, threading it partly along before releasing Ditzen (who at this point realized the catheter was not in her arm) and telling her to call the X-ray department. They walked some distance to the X-ray department on the floor below where, under the guidance of a fluoroscope, he advanced the catheter the full 60 cm into his right ventricular cavity. This was then recorded on X-Ray film showing the catheter lying in his right atrium.

The head clinician at Eberswalde, although initially very annoyed, recognized Werner’s discovery when shown the X-rays; he allowed Forssmann to carry out another catheterization on a terminally ill woman whose condition improved after being given drugs in this way. An unpaid position was created for Forssmann at the Berliner Charité Hospital, working under Ferdinand Sauerbruch.

However, after presenting his paper to Sauerbruch, Forssmann was dismissed for continuing without his approval. Sauerbruch commented, “You certainly can’t begin surgery in that manner.” His surgical skills were certainly noted, but he found it hard to find a job after being fired by several other hospitals because of not meeting scientific expectations or for not respecting hospital policies. After marrying Dr. Elsbet Engel, a specialist in urology in 1933, he quit cardiology and took up urology. He then went on to study urology under Karl Heusch at the Rudolf Virchow Hospital in Berlin. Later, he was appointed Chief of the Surgical Clinic at both the City Hospital at Dresden-Friedrichstadt and the Robert Koch Hospital in Berlin.

From 1932 to 1945, he was a member of the Nazi Party, and at the start of World War II he became a medical officer. In the course of his service, he rose to the rank of Major, until he was captured and put into a U.S. POW camp. Upon his release in 1945, he worked as a lumberjack and then as a country medic in the Black Forest with his wife. In 1950, he began practice as a urologist in Bad Kreuznach.

During the time of his imprisonment, his paper was read by André Frédéric Cournand and Dickinson W. Richards. They developed ways of applying his technique to heart disease diagnosis and research. In 1954, he was given the Leibniz Medal of the German Academy of Sciences. In 1956, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Cournand, Richards, and Forssmann.

After winning the Nobel Prize, he was given the position of Honorary Professor of Surgery and Urology at the University of Mainz. He died in Schopfheim, Germany of heart failure in 1979.