The Mountain Meadows massacre of 1857 remains one of the most controversial events in the history of the American West, and it is called “the darkest deed of the 19th century.” It was a murder of 120 men, women, and children, ordered and planned by southern Utah’s Mormon settlers (members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or the LDS Church).

The massacre began on the 5th of September 1857, when a wagon train loaded with emigrants from Arkansas and heading to California was attacked in southern Utah. The attackers were members of the Utah Territorial Militia from the Iron County district, and some Paiute Native Americans. The story is still controversial, and it is hard to say what was the motivation or why exactly the massacre occurred.

Apparently, in early 1857, there were a few immigrant groups traveling from Arkansas to California. When these groups later joined all together, they formed a group known as the Baker–Fancher party. The name refers to both the Baker train and the Perkins train, but it was soon called the Baker–Fancher train (or party), named after “Colonel” Alexander Fancher who, having already made the journey to California twice before, had become its main leader.

Many of the families in the group were prosperous farmers and cattlemen with ample financial resources to make the journey west. Some of the groups had family and friends in California awaiting their arrival, as well as many relatives remaining in Arkansas.

When the Baker–Fancher party were refused stocks in Salt Lake City, they chose to leave there and take the Old Spanish Trail, which passed through southern Utah. They had traveled the 165 miles south from Salt Lake City, and Mormon missionary – Jacob Hamblin – suggested the wagon train to continue on the trail and rest their cattle at Mountain Meadows, which had good pasture and was adjacent to his homestead.

While many witnesses said that the Fancher’s group was, in general, a peaceful party whose members behaved well along the trail, rumors spread about aggressive and threatening behavior and other misdeeds. Brevet Major James Henry Carleton led the first federal investigation of the murders, published in 1859. He recorded Hamblin’s account that the train was alleged to have poisoned a spring near Corn Creek; this resulted in the deaths of 18 head of cattle and two or three people who ate the contaminated meat.

However, Hamblin’s testimony was based mainly on the prediction of one man – the Second President of LDS Church, the founder of Salt Lake City, and the first governor of the Utah Territory – Brigham Young. Young predicted a seven-year siege which led to a wave of war hysteria among the Mormons, expecting an all-out invasion of apocalyptic significance. There really was an 1858 invasion of the Utah Territory by the United States Army, but it ended up being peaceful.

Carleton interviewed the father of a child who allegedly died from this poisoned spring and accepted the sincerity of the grieving father. However, he also included a statement from an investigator who did not believe the Fancher party was capable of poisoning the spring, given its size. Carleton invited readers to consider a potential explanation for the rumors of misdeeds, noting the general atmosphere of distrust among Mormons for strangers at the time, and that some locals appeared jealous of the Fancher party’s wealth.

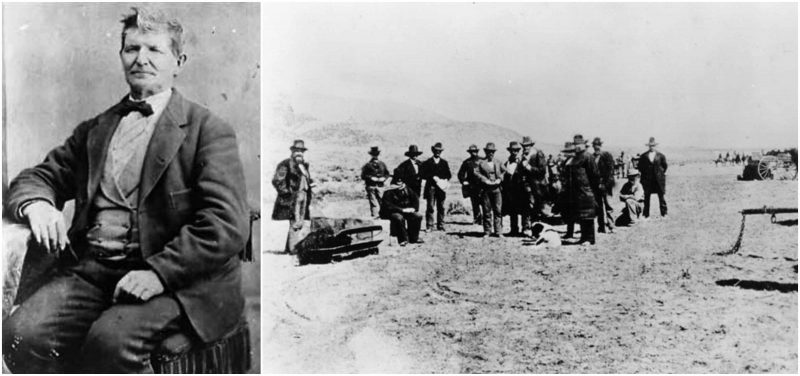

In August 1857, Mormon apostle George A. Smith, of Parowan, set out on a tour of southern Utah, instructing Mormons to stockpile grain. Scholars have asserted that Smith’s tour, speeches, and personal actions contributed to the fear and tension in these communities, and influenced the decision to attack and destroy the Baker–Fancher group. He met with many of the eventual participants in the massacre, including W. H. Dame, Isaac Haight, and John D. Lee. He noted that the militia was organized and ready to fight and that some of them were anxious to “fight and take vengeance for the cruelties that had been inflicted upon us in the States.”

Intending to give the appearance of Native American aggression, the militia’s plan was to arm some Southern Paiute Native Americans and persuade them to join with a larger party of their own militiamen — disguised as Native Americans — in an attack.

During the militia’s first assault on the wagon train, on the 5th of September, the emigrants fought back, leading to a five-day siege. Eventually, militia’s leaders got scared that some emigrants had caught sight of white men and had likely discovered the identity of their attackers and as a result militia commander, William H. Dame ordered his forces to kill the emigrants.

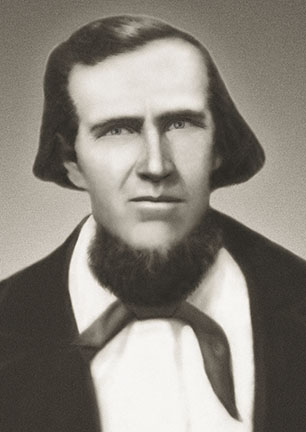

So, on September 11, two militiamen approached the Baker–Fancher party wagons with a white flag and were soon followed by Indian Agent and militia officer John D. Lee. Lee told the battle-weary emigrants that he had negotiated a truce with the Paiutes, whereby they could be escorted safely the 36 miles back to Cedar City under Mormon protection in exchange for turning all of their livestock and supplies over to the Native Americans. Accepting this, the emigrants were led out of their fortification.

The adult men were separated from the women and children. The men were paired with a militia escort. When a signal was given, the militiamen turned and shot the male members of the Baker–Fancher party standing by their side. The women and children were then ambushed and killed by more militia that were hiding in nearby bushes and ravines.

Members of the militia were sworn to secrecy. A plan was set to blame the massacre on the Native Americans. The militia did not kill 17 small children who were deemed too young to relate the story. These children were taken in by local Mormon families. The children were later reclaimed by the U.S. Army and returned to relatives in Arkansas.

During the 1870s John D. Lee, William H. Dame, Philip Klingensmith, Ellott Willden, and George Adair, Jr. were indicted and arrested, while warrants were obtained to pursue the arrests of four others (Haight, Higbee, William C. Stewart and Samuel Jukes) who had gone into hiding. Klingensmith escaped prosecution by agreeing to testify. Brigham Young removed some participants, including Haight and Lee, from the LDS Church in 1870.

The U.S. posted bounties of $500 (equivalent to $9,357 in 2015) each for the capture of Haight, Higbee, and Stewart, while prosecutors chose not to pursue their cases against Dame, Willden, and Adair.

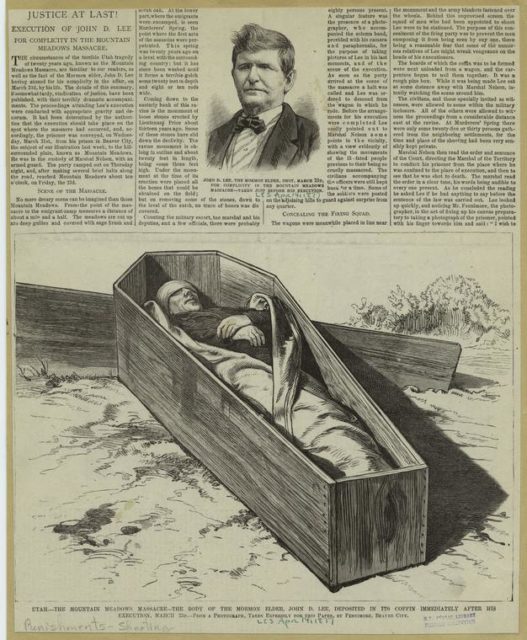

In the end, for what probably stands as one of the four largest mass killings of civilians in United States history, only one man, John D. Lee, ever faced prosecution.