The salt mines of Chehrabad, Iran, provided this essential mineral for more than 2 millennia to anyone who inhabited the vast realm of the former Persian Empire.

When attempts were made in recent years to re-establish the production of salt, for it still represents a basic ingredient in our daily diet, it led in some surprising directions. In 1994, the digging accidentally revealed a mind-blowing discovery. The commercial operation that had been launched literally bumped into an incredibly preserved corpse dating from the period around 1700 B.C.

Needless to say, the excavation prompted Iranian archaeologists to flock to Chehrabad, located some 210 miles northwest of the country’s capital, Tehran. The tiny village in the province of Zanjan, with a population of 378, soon became a place of great interest. More bodies were found in the following archaeological excavations conducted in 2004, 2005, and 2007, which provided a unique insight into the history of the region and the technology that was developed for such complex mining practices.

The reason for the state of the long dead human remains, the fact that their flesh failed to dissolve despite being buried for more than 1,500 years, is the salt, which served as a natural preservative. The remains of six people found on the site were soon dubbed the Saltmen due to this situation.

The first estimate of how many people had been auto-mummified soon rose to eight, after it was determined that some parts belonged to corpses that were yet to be discovered. Just for clarification, the process of auto-mummification is opposite of that of medicinal, intentional mummification.

Such examples include corpses that were preserved by ice, or a special kind of auto-mummification known as Soapman, meaning that human body fat causes a reaction with the clay ground, creating a soap-like protection which mummifies and preserves the flesh.

Together with the preserved flesh and bones in the Chehrabad site, there were pieces of fabric that proved to be extremely useful when it came to different types of analysis, especially for establishing the precise age from which it came.

CC BY-SA 3.0

In the process of determining which period the mummies dated from, crucial help came from Oxford University, which was happy to participate in such a historic find.

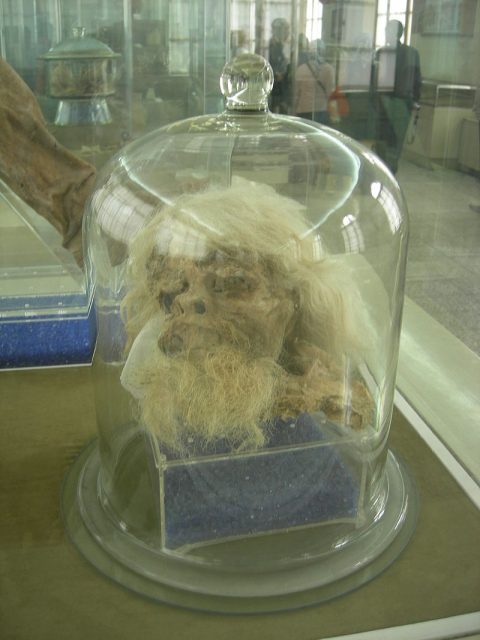

Perhaps the most interesting find is the first one, in which a head with gray hair was discovered by accident, together with his left leg, with a shoe still on. A man in his late thirties, or early forties, was found with his face bashed by a hard object, which was most probably the cause of his death. In fact, it was determined that this was not a burial ground but a real working mine which most probably collapsed numerous times, killing many.

Together with the body, valuable artifacts such as iron knives and a gold earring were found. This confirmed the theory that the first Saltman was a person of great importance and not just a simple salt miner. The head has been transferred to the National Museum of Iran located in Tehran, while five more remains are exhibited in the Zanjan Archaeology Museum.

Photo:Darafsh – CC BY 3.0

Soon it was determined that this man most probably met his demise during the Sasanian Empire. The Sasanids, also known as the Neo-Persians, were the heirs of the ancient Persian Empire, ruling the historically Persian territories from 651 A.D. to 224 A.D.

Apart from focusing on the human remains, the researchers had material to assemble enough data on the history of the ground itself, which appeared to be a source of salt for several developed civilizations throughout different periods, ranging from the early Persian realm called the Achaemenid Empire, together with Parthian and the before-mentioned Sassanid.

Research has been conducted in areas of archaeobotany, archaeozoology, isotope analysis, mining archaeology, and physical anthropology, results of which form a vivid picture of the history of the region and the significant role it played in many variants of the Persian Empire throughout history.

Unfortunately, due to inadequate preservation, some mummified remains had been damaged. A report conducted in 2009 states that the plexiglass casing in which the remains were exhibited was not hermetically closed, which led to almost invisible crack through which bacteria infiltrated the mummies and started to dissolve them, 1,700 years later. Luckily, the report mentions that everything appeared to be under control and that all further deterioration of the mummies was successfully prevented.

What makes the discovery so huge is the fact that there are probably more auto-mummies in the salt mines in Chehrabad, just waiting to be found. And some could be even better preserved than the ones discovered in the last 24 years.