Sweyn Forkbeard was king of Denmark, England, and parts of Norway, his name appears as “Swegen” in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Many details about Sweyn’s life are contested. Scholars disagree about the various, too often contradictory, accounts of his life given in sources from this era of history, such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Adam of Bremen’s Deeds of the Bishops of Hamburg, and the Heimskringla, a 13th-century work by Icelandic author Snorri Sturluson. Conflicting accounts of Sweyn’s later life also appear in the Encomium Emmae Reginae, an 11th-century Latin encomium in honor of his son king Cnut’s queen Emma of Normandy, along with Chronicon ex chronicis by Florence of Worcester, another 11th-century author.

The Dictionary of National Biography states that his mother’s name is unknown, but the Danish encyclopedia Den Store Danske identifies her as Tove from the Western Wendland. Den Store Danske identifies Sweyn’s wife as Gunhild, widow of Erik, king of Sweden,[4] but the Dictionary of National Biography, while agreeing that she was Erik’s widow, describes her as an unnamed sister of Boleslav, ruler of Poland.

Many negative accounts are built on Adam of Bremen’s writings; Adam is said to have watched Sweyn and Scandinavia in general with an “unsympathetic and intolerant eye”, according to some scholars. Adam accused Forkbeard of being a rebellious pagan who persecuted Christians, betrayed his father and expelled German bishops from Scania and Zealand. According to Adam, Sweyn was sent into exile by his father’s German friends and deposed in favor of king Eric the Victorious of Sweden, whom Adam wrote ruled Denmark until his death in 994 or 995.

Historians generally have found problems with Adam’s claims, such as that Sweyn was driven into exile in Scotland for a period as long as fourteen years. As many scholars point out, he built churches in Denmark throughout this period, such as Lund and Roskilde, while he led Danish raids against England.

The “Chronicle of John of Wallingford” (ca. 1225–1250) records Sweyn’s involvement in raids against England during 1002–1005, 1006–1007, and 1009–1012 to revenge the St. Brice’s Day massacre of England’s Danish inhabitants in November 1002. Sweyn was believed to have had a personal interest in the atrocities, with his sister Gunhilde and her husband possibly amongst the victims.

Sweyn campaigned in Wessex and East Anglia in 1003–1004, but a famine forced him to return to Denmark in 1005. Further raids took place in 1006–1007, and in 1009–1012 Thorkell the Tallled a Viking invasion into England. Simon Keynes regards it as uncertain whether Sweyn supported these invasions, but “whatever the case, he was quick to exploit the disruption caused by the activities of Thorkell’s army”.

Some scholars have argued that Sweyn’s participation may have been prompted by his state of impoverishment after having been forced to pay a hefty ransom. He needed revenue from the raids.He acquired massive sums of Danegeld through the raids. In 1013, he is reported to have personally led his forces in a full-scale invasion of England.

The contemporary Peterborough Chronicle (also called the Laud Manuscript), one of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, states:

“before the month of August came king Sweyn with his fleet to Sandwich. He went very quickly about East Anglia into the Humber’s mouth, and so upward along the Trent till he came toGainsborough. Earl Uchtred and all Northumbria quickly bowed to him, as did all the people of the Kingdom of Lindsey, then the people of the Five Boroughs. He was given hostages from each shire. When he understood that all the people had submitted to him, he bade that his force should be provisioned and horsed; he went south with the main part of the invasion force, while some of the invasion force, as well as the hostages, were with his son Cnut. After he came over Watling Street, they went to Oxford, and the town-dwellers soon bowed to him, and gave hostages. From there they went to Winchester, and the people did the same, then eastward to London.”

But the Londoners put up a strong resistance, because King Æthelred and Thorkell the Tall, a Viking leader who had defected to Æthelred, personally held their ground against him in London itself. Sweyn then went west to Bath, where the western thanes submitted to him and gave hostages. The Londoners then followed suit, fearing Sweyn’s revenge if they resisted any longer. King Æthelred sent his sons Edward and Alfred to Normandy, and himself retreated to the Isle of Wight, and then followed them into exile. On Christmas Day 1013 Sweyn was declared King of England.

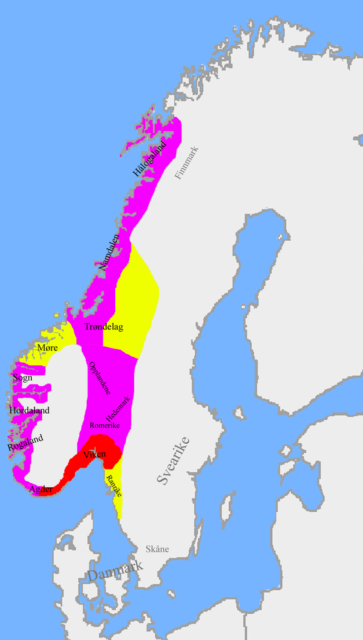

Based in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire, Sweyn began to organise his vast new kingdom, but he died there on 3 February 1014, having ruled England for only five weeks. His embalmed body was returned to Denmark for burial in the church he had built himself. (Tradition locates this church in Roskilde, but it is more plausible that it was actually located in Lund in Scania, now part of Sweden). Sweyn’s elder son, Harald II, succeeded him as King of Denmark, but the Danish fleet in England proclaimed his younger son Cnut king. In England, the councilors had sent for Æthelred, who upon his return from exile in Normandy in the spring of 1014 managed to drive Cnut out of England. But Cnut returned and became King of England in 1016, eventually also ruling Denmark, Norway, parts of Sweden, Pomerania, and Schleswig.

Sweyn’s son Cnut and Cnut’s own sons Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut ruled England for 26 years. After Harthacnut’s death, the English throne reverted to the House of Wessex in the person of King Edward the Confessor (reigned 1042–1066).

Sweyn’s descendants through his daughter Estrid continue to reign in Denmark to this day. One of his descendants, Margaret of Denmark, married James III of Scotland in 1469, introducing Sweyn’s bloodline into the Scottish royal house. After James VI of Scotland inherited the English throne in 1603, Sweyn’s descendants became monarchs of England again.