The great auk (Pinguinus impennis) was a flightless bird of the alcid family that became extinct in the mid-19th century. It was the only modern species in the genus Pinguinus . Although the auk was actually unrelated to penguins, it was the first bird to be called a penguin.

It bred on rocky, isolated islands with easy access to the ocean and a plentiful food supply; a rarity in nature that provided only a few breeding sites for the auks.

When not breeding, the auks spent their time foraging in the waters of the North Atlantic, ranging as far south as northern Spain and also around the coast of Canada, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, Ireland, and Great Britain.

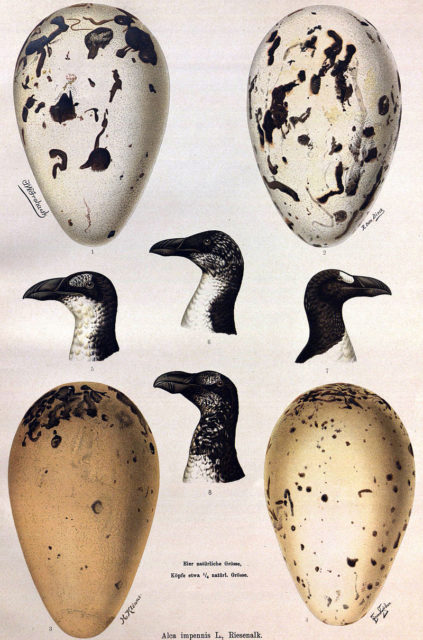

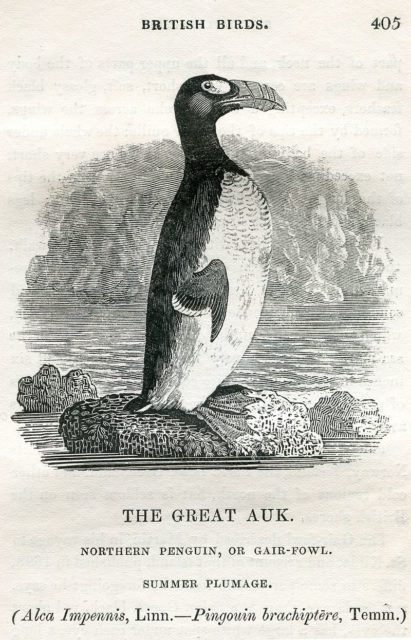

The great auk was 75 to 85 centimeters (30 to 33 in) tall and weighed around 5 kilograms (11 lb), making it the second largest member of the alcid family. It had a black back and a white belly. The black beak was heavy and hooked, with grooves on its surface. During summer, the great auk’s plumage showed a white patch over each eye. During winter, the auk lost these patches, instead developing a white band stretching between the eyes.

The wings were only 15 centimeters (5.9 in) long, rendering the bird flightless. Instead, the auk was a powerful swimmer, a trait that it used in hunting. Its favorite prey was fish, including Atlantic menhaden and capelin, and crustaceans. Although agile in the water, it was clumsy on land. Great auk pairs mated for life.

They nested in extremely dense and social colonies, laying one egg at a time. The egg was white with variable brown marbling. Both parents incubated the egg for about six weeks before the young hatched. The young auk left the nest site after two or three weeks although the parents continued to care for it.

The great auk was an important part of many Native American cultures, both as a food source and as a symbolic item. Many ancient people were buried with great auk bones, and one was buried covered in over 200 auk beaks, which are assumed to have been part of a cloak made of their skins.

Early European explorers to the Americas used the auk as a convenient food source or as fishing bait, reducing its numbers. The bird’s down was in high demand in Europe, a factor which largely eliminated the European populations by the mid-16th century. Scientists soon began to realize that the great auk was disappearing, and it became the beneficiary of many early environmental laws, but this proved not to be enough.

Its growing rarity increased interest from European museums and private collectors in obtaining skins and eggs of the bird. On 3 July 1844, the last two confirmed specimens were killed on Eldey, off the coast of Iceland, which also eliminated the last known breeding attempt.

The Little Ice Age may have reduced the population of the great auk by exposing more of their breeding islands to predation by polar bears, but massive exploitation for their down drastically reduced the population.By the mid-16th century, the nesting colonies along the European side of the Atlantic were nearly all eliminated by humans killing this bird for its down, which was used to make pillows.

In 1553, the auk received its first official protection, and in 1794 Great Britain banned the killing of this species for its feathers. In St. John’s, those violating a 1775 law banning hunting the great auk for its feathers or eggs were publicly flogged, though hunting for use as fishing bait was still permitted. On the North American side, eider down was initially preferred, but once the eiders were nearly driven to extinction in the 1770s, down collectors switched to the auk at the same time that hunting for food, fishing bait, and oil decreased.

The great auk had disappeared from Funk Island by 1800, and an account by Aaron Thomas of HMS Boston from 1794 described how the bird had been systematically slaughtered until then:

If you come for their Feathers you do not give yourself the trouble of killing them, but lay hold of one and pluck the best of the Feathers. You then turn the poor Penguin adrift, with his skin half naked and torn off, to perish at his leasure. This is not a very humane method but it is the common practize. While you abide on this island you are in the constant practize of horrid cruelties for you not only skin them Alive, but you burn them Alive also to cook their Bodies with. You take a kettle with you into which you put a Penguin or two, you kindle a fire under it, and this fire is absolutely made of the unfortunate Penguins themselves. Their bodys being oily soon produce a Flame; there is no wood on the island.

With its increasing rarity, specimens of the great auk and its eggs became collectible and highly prized by wealthy Europeans, and the loss of a vast number of its eggs to collection contributed to the demise of the species. Eggers, individuals who visited the nesting sites of the great auk to collect their eggs, quickly realized that the birds did not all lay their eggs on the same day so that they could make return visits to the same breeding colony. Eggers only collected eggs without embryos growing inside them and typically discarded the eggs with embryos.

On the islet of Stac an Armin, St Kilda, Scotland, in July 1840, the last great auk seen in Britain was caught and killed. Three men from St Kilda caught a single “garefowl,” noticing its little wings and the large white spot on its head. They tied it up and kept it alive for three days until a large storm arose. Believing that the auk was a witch and the cause of the storm, they then killed it by beating it with a stick.

The last colony of great auks lived on Geirfuglasker (the “Great Auk Rock”) off Iceland. This islet was a volcanic rock surrounded by cliffs which made it inaccessible to humans, but in 1830 the islet submerged after a volcanic eruption, and the birds moved to the nearby island of Eldey, which was accessible from a single side. When the colony was initially discovered in 1835, nearly fifty birds were present. Museums, desiring the skins of the auk for preservation and display, quickly began collecting birds from the colony. The last pair, found incubating an egg, was killed there on 3 July 1844, on request from a merchant who wanted specimens, with Jón Brandsson and Sigurður Ísleifsson strangling the adults and Ketill Ketilsson smashing the egg with his boot.

Great auk specialist John Wolley interviewed the two men who killed the last birds, and Ísleifsson described the act as follows:

The rocks were covered with blackbirds [referring to Guillemots] and there were the Geirfugles … They walked slowly. Jón Brandsson crept up with his arms open. The bird that Jón got went into a corner but [mine] was going to the edge of the cliff. It walked like a man … but moved its feet quickly. [I] caught it close to the edge – a precipice many fathoms deep. Its wings lay close to the sides – not hanging out. I took him by the neck and he flapped his wings. He made no cry. I strangled him.

A later claim of a live individual sighted in 1852 on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland has been accepted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN)