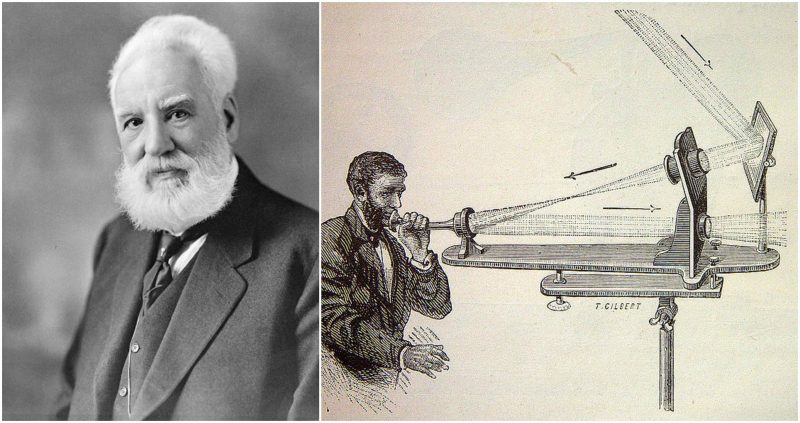

On 3rd June 1880, four years after Graham Bell patented the telephone, he transmitted the first wireless telephone message on his newly invented “Photophone.” All he needed in the 19th century were four years to go from wired voice communications to wireless voice communications. The photophone was in fact, the World’s first device for wireless communications, and it was invented jointly by Alexander Graham Bell and his assistant Charles Sumner Tainter.

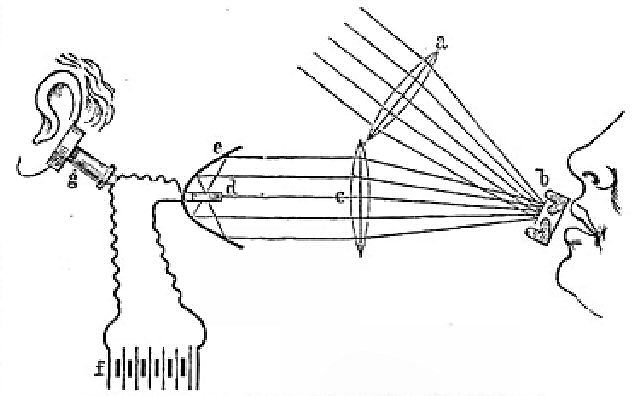

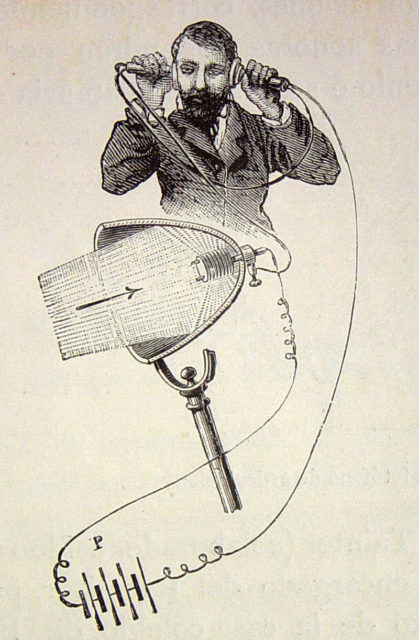

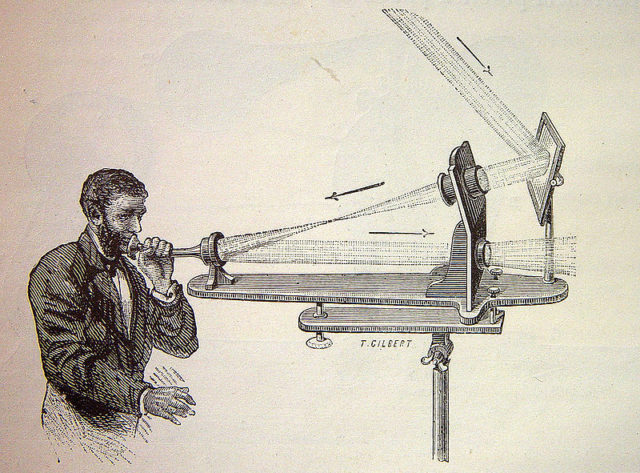

Bell’s photophone was based on transmitting sound on a beam of light. A person’s voice was projected through an instrument toward a mirror. The vibrations of the sound caused similar vibrations in the mirror. Sunlight was then directed to the mirror, where the vibrations were captured and projected back to the photophone’s receiver. There they were converted back into sound. The photophone was similar to a contemporary telephone, except that it used modulated light as a means of wireless transmission while the telephone relied on modulated electricity carried over a conductive wire circuit.

Bell believed that the photophone was his greatest invention. The device allowed the transmission of sound on a beam of light. Of the eighteen patents granted in Bell’s name alone, and the twelve that he shared with his collaborators, four were for the photophone. Shortly before his death, in an interview, Bell referred to the photophone as his “greatest achievement.” He told the reporter that the photophone is “the greatest invention [I have] ever made, greater than the telephone.”

Although the photophone was an incredibly important invention, it was many years before the significance of Bell’s work was fully recognized. Bell’s original photophone failed to protect transmissions from outside interferences such as clouds, that easily disrupted signals. Until the development of modern fiber optics, technology for the secure transport of light inhibited use of Bell’s invention. Bell’s photophone is now recognized as the progenitor of modern fiber optics.

Bell’s description of the light modulator:

We have found that the simplest form of apparatus for producing the effect consists of a plane mirror of flexible material against the back of which the speaker’s voice is directed. Under the action of the voice the mirror becomes alternately convex and concave and thus alternately scatters and condenses the light.

In his speech to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in August 1880, Bell gave credit to the first demonstration of speech transmission by light to Mr. A.C. Brown of London in the Fall of 1878.

The French scientist Ernest Mercadier suggested that the invention should not be named ‘photophone,’ but ‘radiophone,’ as its mirrors reflected the Sun’s radiant energy in multiple bands including the invisible infrared band. For a period, the invention also used the latter name.

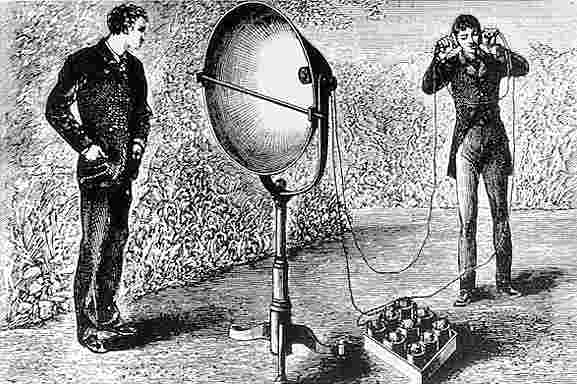

In an April 1, 1880, Washington, D.C. experiment, Bell, and Tainter communicated some 79 meters (259 ft) through an alleyway to the laboratory’s rear window. Then a few months later on June 21, they succeeded in communicating clearly over a distance of some 213 meters (about 700 feet), using plain sunlight as their light source, practical electrical lighting having only just been introduced to the U.S.A. by Edison. The transmitter in their following experiments had sunlight reflected off the surface of a very thin mirror positioned at the end of a speaking tube; as words were spoken they cause the mirror to oscillate between convex and concave, altering the amount of light reflected from its surface to the receiver. Tainter, who was on the roof of the Franklin School, spoke to Bell, who was in his laboratory listening and who signaled back by waving his hat vigorously from the window, as had been requested.

The receiver was a parabolic mirror with selenium cells at its focal point. Conducted from the roof of the Franklin School to Bell’s laboratory at 1325 ‘L’ Street, this was the world’s first formal wireless telephone communication (away from their laboratory). The photophone became the world’s earliest known radiophone and wireless telephone systems, at least 19 years ahead of the first spoken radio transmissions. Before Bell and Tainter had concluded their research to move on to the development of the Graphophone, they had devised some 50 different methods of modulating and demodulating light beams for optical telephony.

The telephone itself was still something of a novelty, and radio was decades away from commercialization. The social resistance to the photophone’s futuristic form of communications could be seen in an 1880 New York Times commentary:

The ordinary man … will find a little difficulty in comprehending how sunbeams are to be used. Does Prof. Bell intend to connect Boston and Cambridge … with a line of sunbeams hung on telegraph posts, and, if so, what diameter are the sunbeams to be ….[and] will it be necessary to insulate them against the weather … until (the public) sees a man going through the streets with a coil of No. 12 sunbeams on his shoulder, and suspending them from pole to pole, there will be a general feeling that there is something about Professor Bell’s photophone which places a tremendous strain on human credulity.

Well, Graham Bell was certainly a man from the future. Perhaps he would have been better suited to the 21st century.

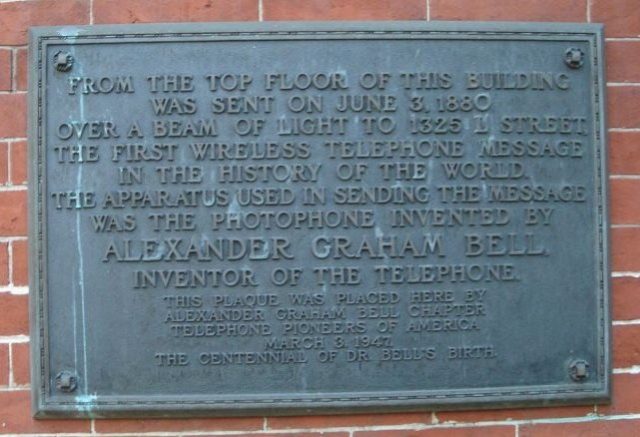

On March 3, 1947, the centenary of Alexander Graham Bell’s birth, the Telephone Pioneers of America dedicated a historical marker on the side of one of the buildings, the Franklin School, which Bell and Sumner Tainter used for their first formal trial involving a considerable distance.

Tainter had stood on the roof of the school building and transmitted to Bell at the window of his laboratory. However, the plaque did not acknowledge Tainter’s scientific and engineering contributions.