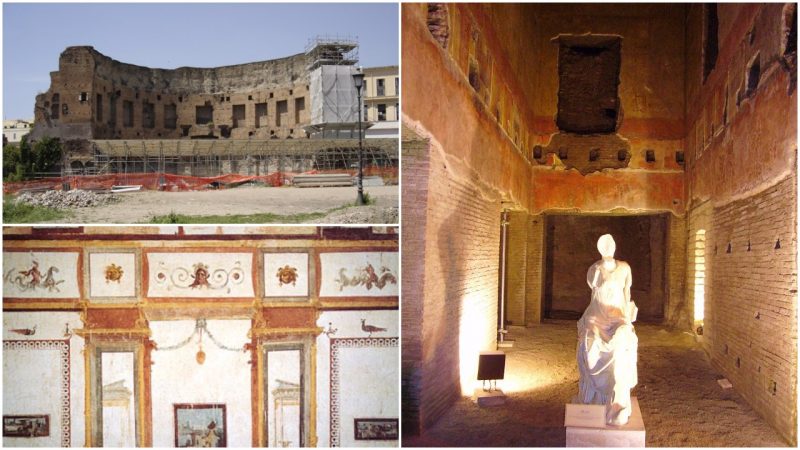

The Domus Aurea or “Golden House” in Latin, was a large landscaped portico villa built by the Emperor Nero in the heart of ancient Rome, after the great fire in 64 AD had cleared away the aristocratic dwellings on the slopes of the Palatine Hill

Built of brick and concrete in the few years between the fire and Nero’s suicide in 68, the extensive gold leaf that gave the villa its name was not the only extravagant element of its decor.

Stuccoed ceilings were faced with semi-precious stones and ivory veneers, while the walls were frescoed, coordinating the decoration into different themes in each major group of rooms. Pliny the Elder watched it being built and mentions it in his Naturalis Historia.

When the edifice was finished in this style and he had dedicated it, he deigned to say nothing more in the way of approval than that he was at last beginning to be housed like a human being.

Though the Domus Aurea complex covered parts of the slopes of the Palatine, Esquiline, and Caelian hills, with a man-made lake in the marshy bottomlands, the estimated size of the Domus Aurea is an approximation, as much of it has not been excavated. Some scholars place it at over 300 acres (1.2 km2), while others estimate its size to have been under 100 acres (0.40 km2).

Suetonius describes the complex as “ruinously prodigal” as it included groves of trees, pastures with flocks, vineyards and an artificial lake — rus in urbe, “countryside in the city”.

Nero also commissioned from the Greek Zenodorus a colossal 35.5 m (120 RF) high bronze statue of himself, the Colossus Neronis. Pliny the Elder, however, puts its height at only 30.3 m (106.5 RF).

The statue was placed just outside the main palace entrance at the terminus of the Via Appia in a large atrium of porticoes that divided the city from the private villa.This statue may have represented Nero as the sun god Sol, as Pliny saw some resemblance.

This idea is widely accepted among scholars, but some are convinced that Nero was not identified with Sol while he was alive.

The face of the statue was modified shortly after Nero’s death during Vespasian’s reign to make it truly a statue of Sol. Hadrian moved it, with the help of the architect Decrianus and 24 elephants, to a position next to the Flavian Amphitheater. This building took the name “Colosseum” in the Middle Ages, after the statue nearby, or, as some historians believe, because of the sheer size of the building.

The Golden House was designed as a place of entertainment, as shown by the presence of 300 rooms without any sleeping quarters. Nero’s own palace remained on the Quirinal Hill. No kitchens or latrines have been discovered either.

Rooms sheathed in dazzling polished white marble were given richly varied floor plans, shaped with niches and exedras that concentrated or dispersed the daylight.

There were pools in the floors and fountains splashing in the corridors. Nero took great interest in every detail of the project, according to Tacitus’ Annals, and oversaw the engineer-architects, Celer and Severus, who were also responsible for the attempted navigable canal with which Nero hoped to link Misenum with Lake Avernus.

The style of wall paintings in Domus Aurea inspired Raphael’s Vatican Stanze and 18th-century Neoclassicism alike.

Some of the extravagances of the Domus Aurea had repercussions for the future.

The architects designed two of the principal dining rooms to flank an octagonal court, surmounted by a dome with a giant central oculus to let in light.It was an early use of Roman concrete construction. One innovation was destined to have an enormous influence on the art of the future.

Nero placed mosaics, previously restricted to floors, in the vaulted ceilings. Only fragments have survived, but that technique was to be copied extensively, eventually ending up as a fundamental feature of Christian art: the apse mosaics that decorate so many churches in Rome, Ravenna, Sicily, and Constantinople.

Celer and Severus also created an ingenious mechanism, cranked by slaves, that made the ceiling underneath the dome revolve like the heavens, while perfume was sprayed and rose petals were dropped on the assembled diners. According to some accounts, perhaps embellished by Nero’s political enemies, on one occasion such quantities of rose petals were dropped that one unlucky guest was asphyxiated (a similar story is told of the Emperor Elagabalus).

“Nero gave the best parties, ever,” archaeologist Wallace-Hadrill told an interviewer when the Golden House was reopened to visitors in 1999 after being closed for years for restorations.

“Three hundred years after his death, tokens bearing his head were still being given out at public spectacles — a memento of the greatest showman of them all. Nero, who was obsessed with his status as an artist, certainly regarded entertainments as works of art. His official elegantiae arbiter, or judge of elegance, was the novelist and courtier Petronius.

Frescoes covered every surface that was not more richly finished. The main artist was one Famulus (or Fabulus according to some sources). Fresco technique, working on damp plaster, demands a speedy and sure touch: Famulus and assistants from his studio covered a spectacular amount of wall area with frescoes. Pliny, in his Natural History, recounts how Famulus went for only a few hours each day to the Golden House, to work while the light was right. The swiftness of Famulus’s execution gives a wonderful unity and astonishing delicacy to his compositions.

Pliny the Elder presents Amulius as one of the principal painters of the Domus urea: “More recently, lived Amulius, a grave and serious personage, but a painter in the florid style. By this artist there was a Minerva, which had the appearance of always looking at the spectators, from whatever point it was viewed.

He only painted a few hours each day, and then with the greatest gravity, for he always kept the toga on, even when in the midst of his implements. The Golden Palace of Nero was the prison-house of this artist’s productions, and hence it is that there are so few of them to be seen elsewhere.”

After Nero’s death, the Golden House was a severe embarrassment to his successors. It was stripped of its marble, its jewels, and its ivory within a decade. Soon after Nero’s death, the palace and grounds, encompassing 2.6 km² (c. 1 mi²), were filled with earth and built over: the Baths of Titus were already being built on part of the site in 79 AD.

On the site of the lake, in the middle of the palace grounds, Vespasian built the Flavian Amphitheatre, which could be reflooded at will, with the Colossus Neronis beside it. The Baths of Trajan, and the Temple of Venus and Rome were also built on the site. Within 40 years, the Golden House was completely obliterated, buried beneath the new constructions, but paradoxically this ensured the wall paintings’ survival by protecting them from dampness.