Born in Germany in 1897, Karl Plagge became permanently disabled after contracting polio as a prisoner during World War I. He graduated with a degree in Engineering and then obtained a Master’s in pharmaceutical chemistry from the University of Frankfurt am Main in 1932. He then ran a medical laboratory in his mother’s house in an attempt to support his family through the recession. He risked his livelihood by continuing to treat Jewish patients and repeatedly condemned racial ‘science’ as unscientific.

As a veteran of World War I, was initially drawn to the promises of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party to rebuild the German economy and national pride during the difficult years that Germany experienced after the signing of the Versailles Treaty. He joined the Nazi Party in 1931 and worked to further its stated goals of national rejuvenation. However, he began to come into conflict with the local party leadership over his refusal to teach Nazi racial theories, which, as a man of science, he did not believe.

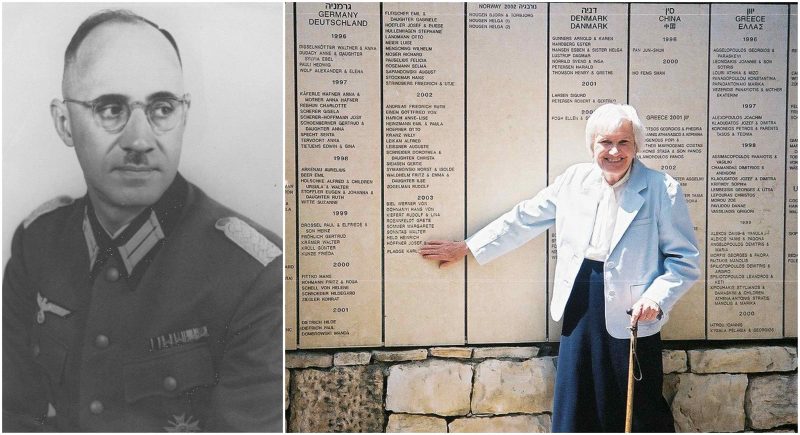

Major Karl Plagge was the commanding officer of HKP unit 562 (vehicle workshop) in Vilnius. He was liberal in granting work certificates and was not particular about the professional skills of the Jewish workers. The workers at the garage included hairdressers, shoemakers, and butchers. Plagge also supplied forged work certificates to rescue Jews from the prison and to transfer them to work in his unit.

This kind of work permit protected the worker, his wife and two of his children from the SS sweeps carried out in the Vilna Ghetto in which Jews without work papers were captured and killed at the nearby Paneriai (Ponary) execution grounds. Plagge issued 250 of these life-saving permits to men, many of them without mechanical skills, thus protecting over 1,000 Jewish men, women, and children from execution from 1941 to mid-1944.

Plagge supported his workers’ survival by procuring extra food rations and supplying hot meals to the workers in his workshops (an unusual measure) to supplement their starvation rations. He also allowed his Jewish male workers to barter for food with his men as well as local gentiles within the workshops so that they could smuggle food back to their families in the ghetto (an illegal activity).

Plagge also aided the survival of the Jews under his jurisdiction by providing warm clothing, medical supplies, and firewood — all scarce commodities. On several occasions, he and his subordinate officers helped secure the freedom of some of his workers or their family members when they were arrested during SS sweeps of the ghetto.

His continued refusal to espouse the Nazi racial teachings led to accusations that he was a “friend of Jews and Freemasons” by the local Darmstadt Nazi leadership in 1935, and he was removed from his leadership positions in the local party apparatus.

In the summer of 1944 the Soviet Red Army advanced to the outskirts of Vilnius. This change in the tides of war brought both joy and fear to the surviving Jews of the HKP camp, who understood that the SS would try to kill them in the days before the German retreat.

On July 1, 1944, Major Plagge entered the camp and made an informal speech to the Jewish prisoners who gathered around him. In the presence of an SS officer, he told the Jews present at his speech that he and his men were being relocated to the west, and that in spite of his requests, he did not have permission to take his skilled Jewish workers with his unit. However, he said that they should not worry, for they too would be relocated on Monday July 3, and that during this relocation they would be escorted by the SS, which as they knew was “an organization devoted to the protection of refugees”.

After the war, Karl Plagge returned home to Darmstadt, Germany, where he was tried in 1947 as part of the postwar denazification process. Some of his former prisoners were in a displaced persons camp in Stuttgart and heard of the charges against him. They sent a representative, on their own initiative and unannounced, to testify on his behalf, and this testimony influenced the trial result in Plagge’s favor.

The court wanted to award Plagge the status of an Entlasteter (“exonerated person”) but on his own wish he was classified as a Mitläufer (“follower”). Like Oskar Schindler, Plagge blamed himself for not having done enough. After the trial, Plagge lived the final decade of his life quietly and without fanfare before dying in Darmstadt in June 1957.

The success of Plagge’s efforts to save Jews is manifested through a survival rate of about 20–25% among those he hired, compared with the much lower rate of 3–5% — virtual annihilation — among the rest of Lithuania’s Jews. The 250 to 300 surviving Jews of the HKP camp constituted the largest single group of survivors of the genocide in Vilnius.