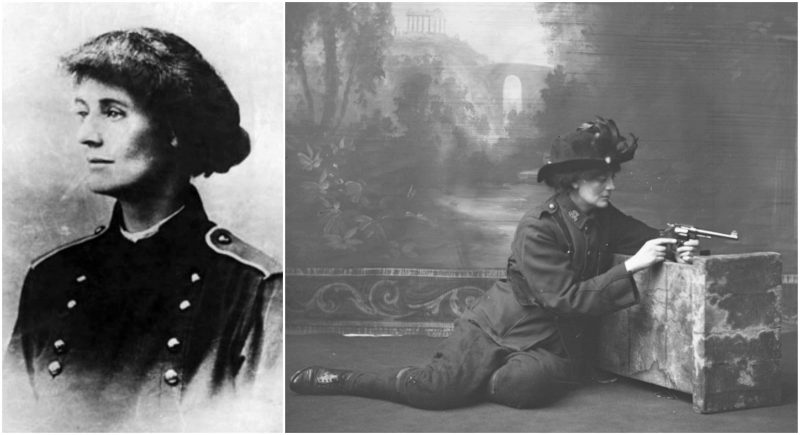

Countess Markievicz played an active part in the Easter Rising of 1916, and also in post-1916 Irish history. Born in 1868 as Constance Gore-Booth, Countess Markievicz was sentenced to death for her part in the Easter Uprising but had the sentence commuted to life incarceration on account of her gender. Her life was full of excitement, and many battles for the causes of suffrage for women or for establishing the independence of the Republic of Ireland from the British rule. There no way to make the long story short in her case.

She was an Irish Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil politician, revolutionary nationalist, suffragette and socialist. In December 1918, she was the first woman elected to the British House of Commons, though she did not take her seat and, along with the other Sinn Féin TDs, formed the first Dáil Éireann. She was also one of the first women in the world to hold a cabinet position, as a Minister for Labour of the Irish Republic, from 1919 to 1922.

Constance Markievicz was born in London. Her Protestant Ascendancy family, the Gore-Booths, owned Lissadell, an extensive estate in Co. Sligo. She was presented at court to Queen Victoria in the monarch’s Jubilee year, 1887. She dismayed her bourgeois family through stubbornly refusing to marry for many years – until she went to art school and there met the penniless Count Casimir Markievicz.

Sarah Purser, an artist and friend of Constance, hosted a regular salon where artists, writers and intellectuals on both sides of the nationalist divide gathered. At Purser’s house, Markievicz met revolutionary patriots Michael Davitt, John O’Leary and Maud Gonne.

In 1906, Markievicz rented a cottage in the countryside near Dublin. The previous tenant, the poet Padraic Colum, had left behind copies of The Peasant and Sinn Féin. These revolutionary journals promoted independence from British rule. Markievicz read these publications and was propelled into action.

In 1908, Markievicz became actively involved in nationalist politics in Ireland. She joined Sinn Féin and in 1909, she already became known to British intelligence for her role in helping found Na Fianna Éireann, a nationalist Scouts organization whose purpose was to train boys for participation in a war of liberation.

In 1911, the Countess was jailed for the first time for her part in the demonstrations that took place against the visit of George V. In the lock-out of 1913, she ran a soup kitchen to aid those who could not afford food.

She soon became an icon of sorts for the women of the rebellion. When asked fashion advice, she told women to “dress suitably in short skirts and strong boots, leave your jewels in the bank, and buy a revolver.” In later parades, she showed up so heavily armed “that the casual onlooker might be readily pardoned for mistaking her for the representative of an enterprising firm of small arms manufacturers.”

As a member of the ICA, Markievicz took part in the 1916 Easter Rising. She was deeply inspired by the founder of the ICA, James Connolly. Markievicz designed the Citizen Army uniform and composed its anthem, based on the tune of a Polish song.

In the Rising, Markievicz fought in St Stephen’s Green, where on the first morning — according to one account — she shot a member of the (unarmed) Dublin Metropolitan Police, who subsequently died of his injuries. Other accounts placed her at City Hall when the police officer was shot, only arriving at Stephen’s Green later.

It was long thought that she was second in command to Michael Mallin, but in fact, it was Christopher Poole who held that position. Markievicz supervised the setting-up of barricades on Easter Monday and was in the middle of the fighting all around Stephen’s Green, wounding a British army sniper.

The rebellion was ill-fated. The English overwhelmed the isolated (and soon starving) pockets of rebels with superior numbers, training, and equipment. A week in, the rebel leadership spread the order to surrender. Upon receiving word of this, Constance turned herself in with maximum theatricality: gently kissing her gun before handing it over and declaring, “I am ready.”

While many of her cohorts were executed by firing squad, her execution was commuted to life imprisonment. It was an act of mercy she met with fury: “why didn’t they let me die with my friends!?”

However, she was released from prison in 1917, along with others involved in the Rising, as the government in London granted a general amnesty for those who had participated in it. It was around this time that Markievicz, born into the Church of Ireland, converted to Catholicism.

At the 1918 general election, Markievicz was elected for the constituency of Dublin St Patrick’s, beating her opponent William Field with 66% of the vote, as one of 73 Sinn Féin MPs. This made her the first woman elected to the British House of Commons. However, in line with Sinn Féin abstentionist policy, she would not take her seat in the Parliament.

Markievicz served as Minister for Labour from April 1919 to January 1922, in the Second Ministry and the Third Ministry of the Dáil. Holding cabinet rank from April to August 1919, she became both the first Irish female Cabinet Minister and at the same time, only the second female government minister in Europe. She was the only female cabinet minister in Irish history until 1979 when Máire Geoghegan-Quinn was appointed to the cabinet post of Minister for the Gaeltacht for Fianna Fáil.

Markievicz left the government in January 1922 along with Éamon de Valera and others in opposition to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. She fought actively for the Republican cause in the Irish Civil War, helping to defend Moran’s Hotel in Dublin. After the War, she toured the United States.

The Countess was also re-elected to the Dáil, but her staunch republican views led her to be sent to jail again. In prison, she and 92 other female prisoners went on hunger strike. Within a month, the Countess was released. The hunger-strikes of the Suffragettes had been a huge embarrassment to the British government before the war. The newly created Dáil could barely afford a similar scandal. In 1926, the Countess joined Fianna Fáil led by Eamonn de Valera. She died in 1927. It is estimated that over 250,000 people lined the streets for her funeral in Dublin and de Valera read the eulogy.