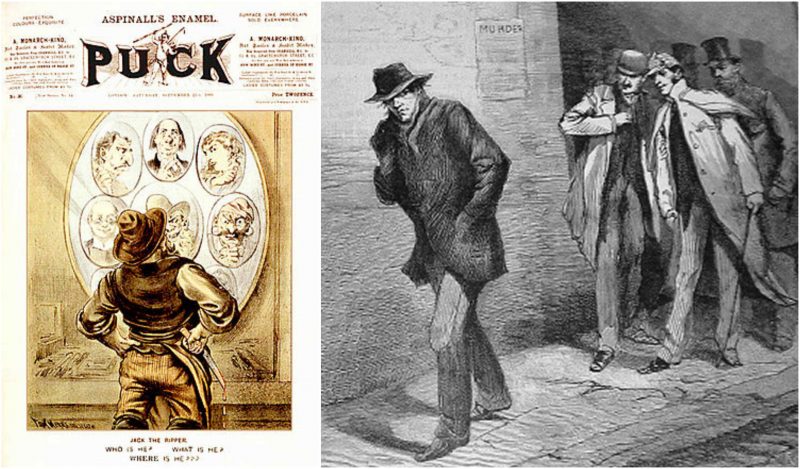

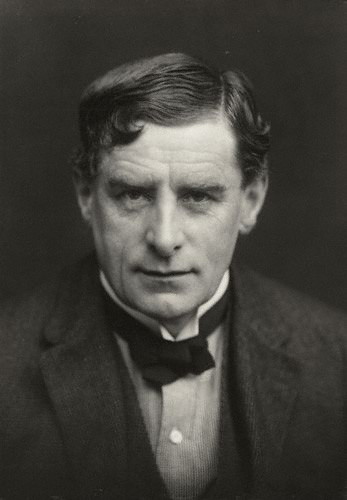

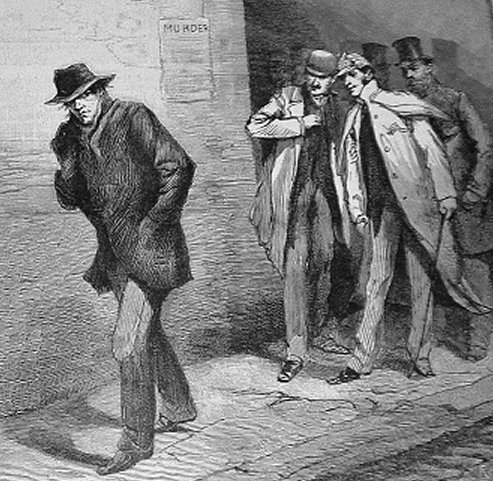

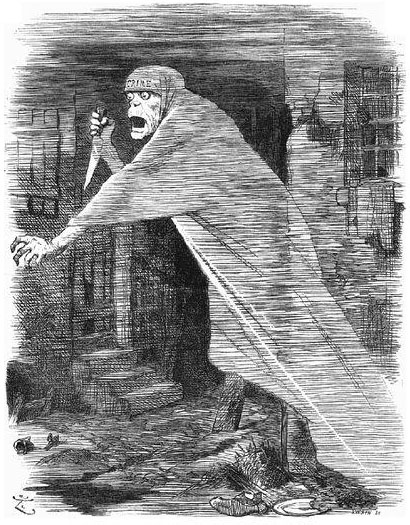

From August to November of 1888, the Whitechapel District in the East End of London, one of the poorest sections of the city in Victorian times, was the scene of five vicious slayings. The murderer was given the nickname “Jack the Ripper” after a letter with that signature arrived at a London newspaper on November 27th taunting the police with sentences such as “My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance.” It’s never been confirmed that the “Dear Boss” letter came from the same person who murdered the women, all of them prostitutes and all but one shockingly mutilated. But the name stuck.

As the killer seemed to know human anatomy, evidenced by the way in which he mutilated his victims, often in the darkness and within minutes, it has been suggested that he (or she) was either a butcher or a doctor. A butcher was briefly held by the police but then released. He had an alibi for the murder being investigated. All other local butchers were investigated and cleared. There is a myth of indifferent police work. In fact, a large group of police put enormous effort into trying to capture Jack the Ripper, including a door-to-door questioning. Even Queen Victoria was distressed by the police force’s lack of success.

The victims were Mary Ann Nichols, killed August 31, 1888; Annie Chapman, killed September 6, 1888;Elizabeth Stride, killed September 30, 1888; Catherine Eddows, killed September 30, 1888; and Mary Jane Kelly, killed November 9, 1888. These women are referred to as the “canonical five,” the ones who most researchers believe were killed by the same person. There are a few more women who were murdered at roughly the same time with some mutilation, but their link to the Ripper was tenuous and mostly disproved.

Books have been written, Hollywood movies have been made, and theories have been debated for more than 100 years, but, despite this, the identity of Jack the Ripper has never been established. Some of the theories as to his identity are plausible, and some are extremely far-fetched, but regardless, they just keep coming. Here are nine suspects.

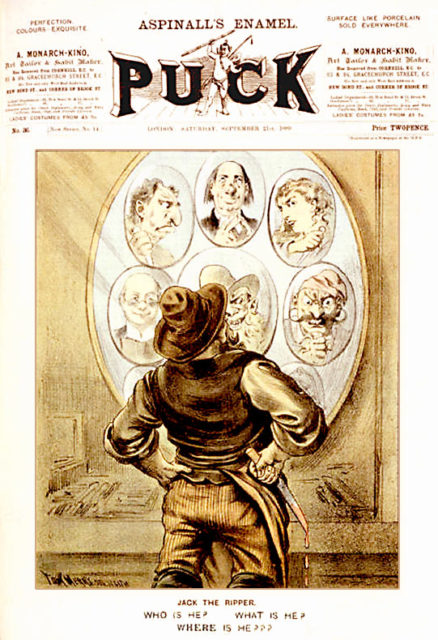

9. Walter Sickert

Sickert was a painter who lived from 1860 until 1942. Of German origin, his parents settled in England in 1868. Sickert took up the serious study of art in 1881 and was a contemporary of Edgar Degas and James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Sickert taught at the Westminster School of Art and an avid Ripperologist–the name later adopted by those who study the Jack the Ripper crimes. Sickert’s name was never mentioned as a suspect while he was alive. In 1976, Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution was published by Stephen Knight. From what he had been told by Joseph Gorman, who was, allegedly, Sickert’s son by his Paris mistress, Knight believed Sickert was forced to become an accomplice of the Ripper. Later, Gorman admitted his story was untrue, but it was too late to stop a conspiracy theory that extended to members of the royal family and the Freemasons.

In 1990, Jean Overton Fuller published Sickert and the Ripper Crimes: The Original Investigation into the 1888 Ripper Murders and the Artist Richard Walter Sickert. Fuller claims to have received information from her mother’s friend, artist Florence Pash, who was also a friend of Sickert’s, that Pash had found clues in Sickert’s paintings that identify him as the Ripper.

A third modern publication, Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper— Case Closed, written in 2002 by Patricia Cornwell, also maintains that Sickert was Jack the Ripper. Cornwell claimed she was able to technically prove that mitochondrial DNA from many of the Ripper letters received by Scotland Yard, as well as mitochondrial DNA from a letter written by Sickert, prove the painter’s guilt. Another book, written by Cornwell in 2017, Ripper: The Secret Life of Walter Sickert, chronicles what the author believes to be additional evidence for Sickert’s guilt.

8. Carl Feigenbaum

In 1894, in New York City, Carl Feigenbaum, a merchant seaman, was arrested for cutting the throat of his landlady, Mrs. Juliana Hoffmann, as she slept. William Sanford Lawton, Feigenbaum’s lawyer, claimed that Feigenbaum had confessed his hatred of women and his craving to kill and disfigure them. Lawton himself believed Feigenbaum was Jack the Ripper.

Feigenbaum was executed in April of 1896 for the murder of Mrs. Hoffman. Using Lawton’s allegations, author and former British murder squad detective Trevor Marriott pursued Feigenbaum’s responsibility for not only the Ripper murders but additional murders in Germany and the United States. He based his claim on research that shows that in 1891 and 1894, Feigenbaum served on merchant ships that had been docked near Whitechapel on the date of each of the Ripper murders.

7. Dr. John Williams

Dr. Williams was a celebrated doctor, surgeon, and teacher in 1880s London. In 2005, Tony Williams, a descendant of Dr. Williams, published a book entitled Uncle Jack. In the book, Williams claims that Dr. Williams shadowed Whitechapel looking for women he may have met at his clinic.

The claim was that he killed them and took their uteri to take back to the hospital for study in an attempt to cure his wife’s sterility. Williams offered no actual proof; his book is filled with conjecture and open phrases such as “perhaps” and “we don’t know, but…”

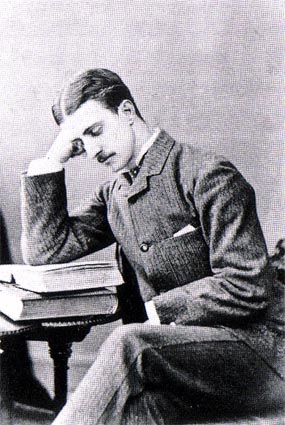

6. Montague Druitt

On December 31, 1888, the dead body of Oxford-educated lawyer, teacher, and avid cricket player Montague Druitt was pulled out of the River Thames. Detectives determined that the cause of death was suicide. The body, which was weighted down by rocks in the pockets, had been in the river for several weeks. Druitt had been deeply despondent after much misfortune, such as his dismissal from a teaching post at George Valentine’s boarding school, his mother’s committal to an asylum due to severe depression, and the added grief over his father’s death from a heart attack in 1885.

Again, no tangible evidence connects him with the Ripper murders, and it was only due to the fact that the murders ended so soon after Druitt’s death that London detective Melville Leslie Macnaghten thought to identify Druitt as one of the top three suspects. It was through assumption and circumstantial evidence alone that the arguments against Macnaghten were made.

There was a history of suicide and mental illness on Druitt’s maternal side of the family, and the theory goes that dismissal from his teaching post could very well have triggered depression, anger, and violence.

However, Inspector Frederick Abberline, the leading investigator in the case, didn’t agree that the Ripper must have died right after the killings in the autumn of 1888. In his interview with the Pall Mall Gazette in 1903, he is quoted as saying, “You can state most emphatically that Scotland Yard is really no wiser on the subject than it was fifteen years ago. It is simple nonsense to talk of the police as having proof that the man is dead. I am, and always have been, in the closest touch with Scotland Yard, and it would have been next to impossible for me not to have known all about it. Besides, the authorities would have been only too glad to make an end of such a mystery, if only for their own credit.”

5. Robert Mann

In 2009, British historian Mei Trow stated he had solved the mystery of Jack the Ripper’s identity with modern forensics and psychological profiling. He implicated Robert Mann, a mortuary worker in Whitechapel. Present day criminologists believe the Ripper had a tough childhood and came from a low socio-economic status, unlike previous theories of his being a well-to-do murderer.

Mann spent part of his childhood in a poorhouse and worked with deceased bodies. According to the probe into the murder of Polly Nichols, Mann unnecessarily removed her clothing at the morgue which, according to Trow, was to admire his work. Again, assumption played a large part here.

4. Jill the Ripper

Mary Pearcey was made a suspect in the Jack the Ripper mystery—the only female suspect at the time. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who authored the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, wondered if the Ripper may have been a female, theorizing that a woman could be seen in public in bloody clothes at any time of night, as many would assume she was a midwife.

The fact that Pearcey had stabbed her lover’s wife and child to death and cut their throats in October of 1890 led investigators to believe she could be a candidate. In 2006, a study by Australian scientist Ian Findlay gave credibility to the female Ripper idea. Findlay went to London to collect DNA samples from the few Jack the Ripper letters believed to be credible. He used new technology to create a profile. The findings were inconclusive but did indicate the sender could have been a woman.

In his 1939 book, Jack the Ripper: A New Theory, William Stewart attempted to link Pearcy by assumption and hearsay evidence given by a local resident, Caroline Maxwell, but, again, nothing concrete was put forward.

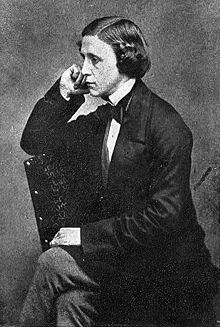

3. Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, writing under the name of Lewis Carroll, was the author of the Alice in Wonderland series of books published in the mid-1860s. In the book Jack the Ripper, Light-Hearted Friend, published in 1996, Richard Wallace asserted that Dodgson and Thomas Vere Bayne, a colleague, were responsible for the murders attributed to Jack the Ripper.

His evidence consisted of anagrams he created out of Dodgson’s work that he said were admissions of Dodgson’s alleged crimes. Unfortunately, according to Casebook.org, one could rearrange the words in any writing and make half-connected sentences suggestive of almost anything. Also, the fact that Wallace disregards or changes letters in the work that do not agree with his ideas, makes the case for the beloved children’s author being a serial killer highly unlikely.

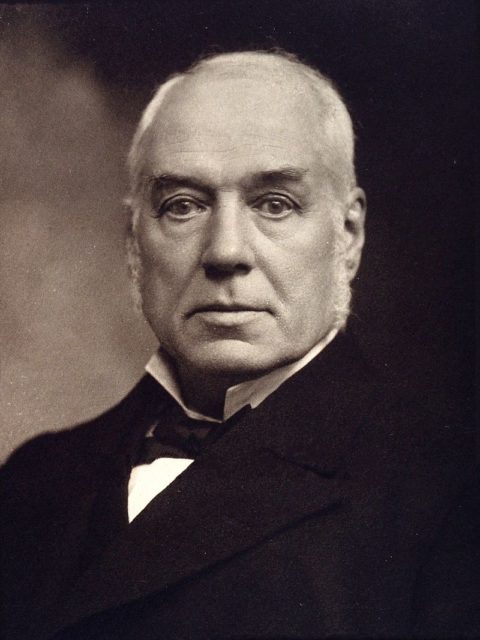

2. Lord Randolph Churchill

The father of Sir Winston Churchill, former prime minister of England, has been offered as a candidate. Included in the Freemason conspiracy theories, according to author Melvyn Fairclough, Lord Churchill was the highest-ranked Freemason; it was his responsibility to protect the name of the royal family and the Crown. Supposedly, he formed a group that included Sir William Gull, John Netley, Frederico Albericci, and J.K Stephen to kill five prostitutes who were under the tutelage of Mary Kelly. It was supposedly feared that they had knowledge of Prince Albert Victor’s secret marriage to a Whitechapel woman named Annie Elizabeth Crook and were in a position to blackmail the royal family.

Not only is there no evidence linking Lord Churchill to the Freemasons, but there is no evidence that such a marriage was ever solemnized. Nor is there evidence linking Mary Kelly, the last of the canonical five to die, with the earlier victims.

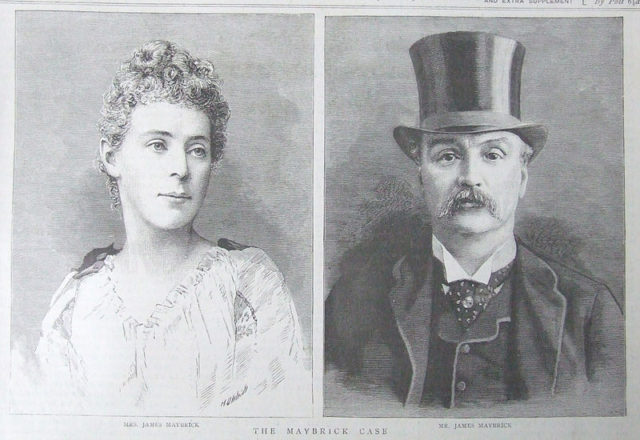

1. James Maybrick

James Maybrick is the most plausible subject, according to Ripperologists’ votes on the website Jack the Ripper Casebook.

Maybrick, a Liverpool cotton broker, was named as Jack the Ripper due to a diary received by Michael Barrett, a former merchant seaman and scrap dealer. The diary was given to Barrett by Tony Devereux, who never revealed the circumstances under which he received it. It was allegedly written by Maybrick, signed Jack the Ripper, and detailed the murders of Mary Kelly, Annie Chapman, and Mary Ann Nichols. The details from the diary, however, were false. The ink from the diary was tested several times for dating, but tests were inconclusive. In a sworn statement in 1995, Michael Barrett confirmed Jack the Ripper was the author of the diary, but he later withdrew his statement, saying he forged the journal himself. He later denied that he had forged the book, but then changed his statement again, stating that he had, in fact, forged it. Although Barrett claimed the diary was given to him by Devereaux who had since passed away, his wife maintained it had been in her family for generations.

In 1993, Albert Johnson of Wallasey produced a pocket watch of Victorian origin. On the inside cover, the name J. Maybrick appears along with the initials of the five canonical victims. Subsequent testing showed the name and initials were also of Victorian origin and would have been nearly impossible to fake.

Hollywood has produced more than 100 movies and TV shows featuring a Jack the Ripper character. The first was Waxworks, a 1924 movie produced by Neptune-Film A.G. The most recent is a 2017 documentary that explores the conspiracy theories between Jack the Ripper, the Freemasons, and even William Shakespeare. Most offer conjecture, assumption, and blatantly incorrect facts.

Hundreds of names have been put forward as being the real Jack the Ripper, but as of yet, none have been authenticated. The mystery continues to draw out many conspiracy theories, hoaxes, and misleading “facts” that will be studied for years to come.