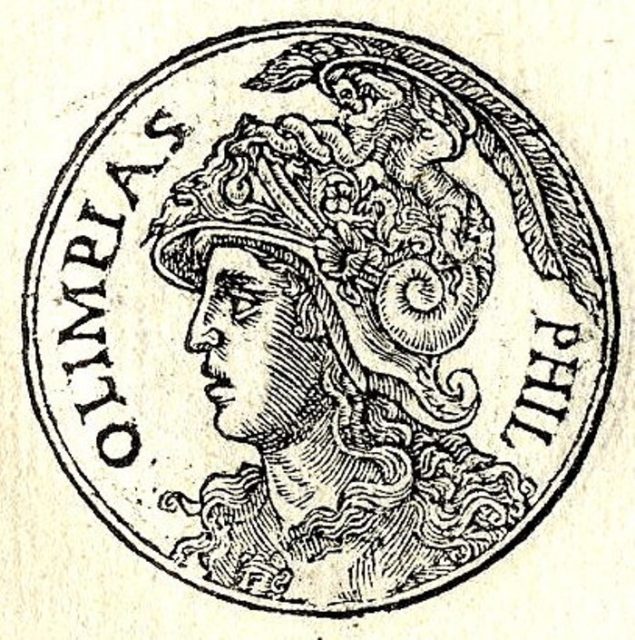

Last year, an opulent underground monument — dating from the 4th century BC — in northern Greece caused a frenzy on the global scale when it was revealed to have possibly been the final resting place of Alexander the Great.

One complete skeleton was uncovered in the large burial ground. Incomplete remains from an elderly woman — hoped to be Alexander’s mother — the bones of two men, and remains of a newborn baby were the other discoveries.

Due to these finds, experts have opened the second phase of their excavation in hopes uncovering more burial chambers. These chambers could potentially hold ancient members of the Macedonian royal family, or even possibly the warrior king Alexander the Great himself. Greek Culture Minister Costas Tasoulas visited the burial mound to announce the new phase of the exploration.

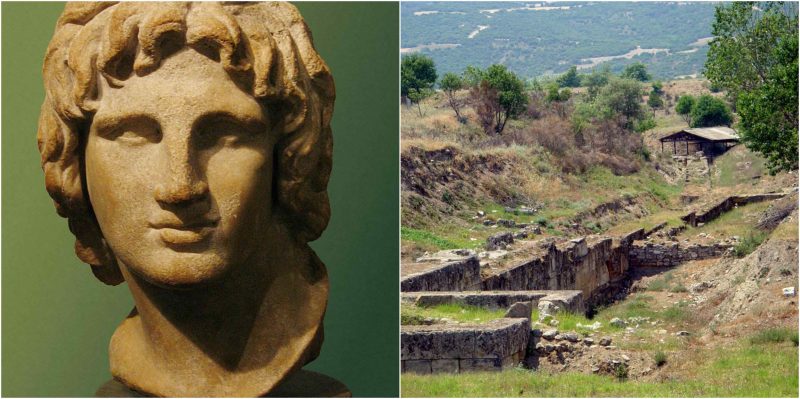

The intact skeleton was found during the first search of the site. Noting the opulent statues and mosaic floor, experts believe that the person had likely been an important general. He was of medium height with pale skin and brown or red hair. This suggests that the remains could very well belong to the blue-eyed king, Alexander the Great, who was reputed to have strawberry blonde hair. Other experts are less sure about those conclusions and question whether they correctly sexed the skeleton.

Just for a quick refresher: Alexander the Great (or Alexander the III of Macedon, as he was also called) was born in Pella, the ancient capital of Macedonia in July 356 BC. He would lead his army across the Persian territories of Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt, claiming the land as he went. His greatest victory, however, occurred at the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC—modern-day northern Iraq. During his trek across these Persian territories, he was said to never have suffered a defeat; this is what spurred people to title him “Alexander the Great.” Following this battle in Gaugamela, Alexander led his army a further 11,000 miles (17,700km) and founded over 70 cities. The empire he created stretched across three continents. This covered from Greece in the west, to Egypt in the south, Danube in the north, and Indian Punjab to the East. After Alexander died in Babylon of a fever in 323 BC, he was buried in Egypt, but it is thought his body was moved to prevent looting. His fellow royals were traditionally interred in a cemetery near Vergina, far to the west.

Currently, the skeleton is undergoing DNA analysis to figure out if the person was a member of the Macedonian royal family. They might even learn his approximant age. Once they have the DNA, researchers will compare it with the DNA from Phillip II, who was the father of Alexander the Great. Phillip II’s tomb was discovered in the 1970s. This still is not without its own issues. According to Lina Mendoni, the Culture Ministry’s general secretary, Phillip II’s DNA is “overworked” and thus might not be reliable. The DNA tests on Phillip II’s bones were conducted fifty years ago. Furthermore, his bones had been burnt and possibly contaminated. Even if the DNA was recovered from the unknown skeleton, however, the gender of that person may never be known, explained Mendoni.

Theories as to the identity of the skeleton vary. Some experts suggest that the remains could be Alexander’s widow, while others claim that it is his son or half-brother. Yet another theory names the skeleton as Nearchos, who was one of Alexander’s closest aides and a native to Amphipolis.

Unfortunately, robbers have stripped the mound of its valuable artifacts, so no clues about the identity of the human remains could be gathered from them. Had any personal affects been buried with their owner, it could have led researchers to a revelation. Michalis Tiverios, a professor of archaeology at the University of Thessaloniki who has not been involved with the dig, noted, “Whatever objects of value the first thieves missed was taken by others later.”

This has not stymied the archaeologists, however. Geophysicists are using scanners to examine the site to determine whether there are other structures inside, aside from the three-chamber tomb already found, of course. The current area being scanned is a mere one-seventh of the total area of the mound.

Inside the three-chambered tomb, archaeologists are still uncovering multicolored decorations, as well as statues, such as the two sphinx statues on the entrance. A bust — that of another sphynx — iron and bronze nails, carved bone, and glass decorations thought to be from the coffin have also all been found inside the tomb.

The damage floor mosaic depicts Hades, the ancient Greek god of the underworld, as he abducts the goddess Persephone on a horse-drawn chariot, while the god Hermes looks on. Peristeri and Michalis Lefantzis, her head architect, said they had found three inscriptions with the word ‘parelavon’ (received) and Hephaestion’s monogram.

The skeletal remains were found both inside and outside the rectangular stone-lined cist, lying under the floor of the cavernous, vaulted structure that measures twenty-six feet (eight meters) tall. The body that was recovered, revealed Greece’s Ministry of Culture, had apparently been buried in a wooden coffin—this coffin had, naturally, disintegrated by this point and thus no longer exists.

Identity of the remains aside, Professor Tiverios emphasized the importance of such a find. The human remains could still provide some insight to the occupant of the tomb. The tomb itself is (literally) a big deal, measuring at 49 feet (15 meters) long and 15 feet (4.5 meters) wide. It is one of the biggest ever found in the country.

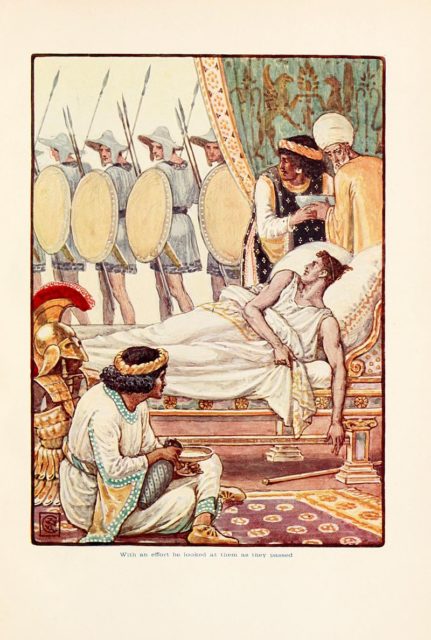

Katerina Peristeri, the lead archaeologist on the excavation, has a different suggestion. She believes that the vaulted structure, decorated with sculptures and a mosaic floor, was a funerary monument for Hephaestion.

Who was Hephaestion? He was essentially Alexander the Great’s best friend. The Macedonian nobleman grew up with Alexander and served as a general in his army. He also served as a member of Alexander’s personal bodyguard. During the king’s ten-year campaign in Asia, he was entrusted with many tasks.

His physical powers aside, Hephaestion was known to correspond with philosophers such as Aristotle and Xenocrates, and he actively supported Alexander in his attempts to integrate the various cultures within his empire. Alexander the Great and Hephaestion were brothers in law — Alexander gave his wife’s sister to Hephaestion as a bride. Both women, Drypetis and Stateira, were daughters of Darius III of Persia.

Dying in Persia in 324 BC, Hephaestion was only around thirty-two when he perished. It was a whole year before his friend would die. In his grief, Alexander ordered a series of monuments to be built across his newly won empire. Not only that, but the king also petitioned the oracle at Siwa to grant Hephaestion divine status. He was successful and Hephaestion was honored as a divine hero.

All that is known about Hephaestion after that is that his body was cremated at Babylon in the presence of the entire army, but no one knows where he was finally laid to rest.

The underground complex, located in Amhipolis, east of Thessaloniki, is a monument, not a tomb. Peristeri explained that there is no evidence that Hephaestion was ever buried there.

“We surmise it was a funerary heroon (hero worship shrine) dedicated to Hephaestion,” she said, “I do not know if he is buried inside.” The mound is believed to have been built between 300 to 325 BC for some as-of-yet unknown prominent Macedonian person.

Greece’s Culture Ministry added their stance, “It is probably the monument of a dead person who became a hero, meaning a mortal who was worshipped by society at that time. “The deceased was a prominent person, since only this could explain the construction of this unique burial complex. It is an extremely expensive construction, whose cost, clearly, is unlikely to have been borne by a private citizen.”

As for what we do know about Hephaestion, we must turn to the ancient historian Plutarch, who is the source for much of our knowledge about Hephaestion’s death and Alexander’s reaction. According to Peristeri, he wrote that when Hephaestion died in what would become modern-day Ecbatana, Iran, the architect Deinoskrates was tasked with the mission to erect shrines all over the country.