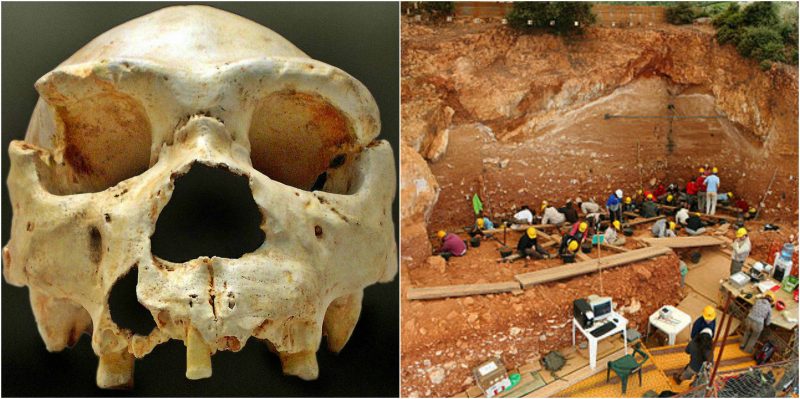

Archaeologists have discovered what might have been the world’s first murder, dating back 430,000 years. Investigators say that lethal wounds identified on a human skull in Spain are possible evidence of the first case of homicide in history. They concluded that a primitive man was killed by two blows to his head just above the left eye, received the same object.

The excavation site in northern Spain, Sima de Los Huesos, is placed deep inside an underground cave and holds the skeletal remains of at least 28 people. An almost complete skull consisting of 52 fragments was discovered during an excavation that has taken place over the past 20 years, and it now has been put together with extraordinary results. Specifically, the scientists revealed that two fractures located at the front of the skull were most likely to have been intentionally caused by some other primitive human.

There is only one access to the site, through a shaft that is 43 feet long, and how the bodies were brought there is still a mystery. The researchers state the injuries are most likely to be the consequence of falling instead of evidence of an act of aggression. Alternatively, they could also be the indication of an act of deadly assault.

The Atapuerca Mountains, where the skulls were discovered, are located in the Spanish province of Burgos, near Ibeas de Juarros and Atapuerca. The cave has been labeled “the Pit of Bones,” and it is one of the richest sources of prehistoric fossils within Europe. In 2013, scientists extracted DNA from the fossilized leg bone found at the same site. The human passed away about 400,000 years ago. Its DNA series proves it was closely related to an earlier human species found in Siberia around 700,000 years ago, and the European Neanderthals who thrived until 30,000 years ago.

An investigation of remains found at the site last year also discovered that early Neanderthal man utilized his mouth as a third hand. A study reinforces theories that Neanderthals developed their characteristic looks at a slow pace, and sporadically, over thousands of years. For example, research on a collection of skulls within the cave recommended that the predecessors of the Neanderthals used their teeth as a vice for carrying objects and tearing apart meat.

Modern humans and Neanderthals are believed to have had co-existed for thousands of years and interbred with each other. These genes have been connected to an increased risk of Type 2 diabetes by new analyses of our evolutionary history. Nevertheless, other genes we inherited from other species possibly improved our immune systems. A study from last year by scientists at Plymouth and Oxford University found that the genes are thought to contain some of the risk factors of cancer, which were discovered within the Neanderthal genome. In an article published in January in Nature magazine, a team from Harvard School claimed that a gene that may cause diabetes in Latin Americans originated with the Neanderthals.

The ancient skulls at the “Pit of Bones” display Neanderthal features in the teeth and face, while some other parts of the skulls, including the brain casing, corresponded to those of modern humans. This suggests the oldest Neanderthals utilized their jaws in a specific way for chewing, as well for holding objects. The findings at the Sima de Los Huesos site have allowed scientists to improve their understanding of human evolution throughout the duration of the Middle Pleistocene period. This was a time in the journey of hominid evolution that has been ferociously debated.

Juan-Luis Arsuaga, who is a paleontologist at Complutense University in Madrid, was involved in the 2014 study and most of the recent research. He has claimed the discoveries showed that different species of early humans competed for habitable areas about 400,000 years ago. The Middle Pleistocene was a lengthy period, of approximately half a million years: however, for human evolution, it was a slow process of change, with only one kind of hominid evolving towards the early Neanderthal. The skulls were found to possibly have characterized the cranial morphology of the human population of the European Middle Pleistocene for the very first time. About 400,000 to 500,000 years ago, some early humans split off from the other groups of that period, expanding into Africa and Eurasia. Once they had settled, they evolved characteristics that would start to define the Neanderthal line of descent.

They crossbred with the Neanderthals but displayed signs of incompatibility. Because of this, modern humans sooner or later replaced the Neanderthals. The degree of divergence between modern humans and Neanderthals over a short period has long perplexed scientists. Until now, it has been challenging to fill the gaps because European fossil records are dispersed and isolated.

The site of Sima de Los Hueses has been one of the biggest discoveries of human fossils in the past 20 years; scientists have recovered 7,000 fossils corresponding to all skeletal areas of at least 28 individuals. This outstanding collection includes 17 skulls, several of which are complete. The skulls belong to a single population of a fossil hominid species. Several of them have been studied before, but seven are presented anew here, and six are more complete than they were before.