Wars get the worst of us. But just how far does that “worst” go? It is generally forgotten that during WWII some US soldiers went as far as to mutilate the dead Japanese and turn their body parts into souvenirs. And then send them to their folks back home. Mutilation was so widespread, that the Army chiefs had to intervene.

United States’ entry into WWII marked a turning point in the global conflict. The country was kind of standing aside until the Japanese bombed the US naval base at Perl Harbor, on the morning of December 7th, 1941. The extent of the fury thus unleashed was to be witnessed long after the war was over.

The Americans set off primarily to fight the Japanese in the Pacific Theatre. But the news reports of their military advances were at times quite bizarre, at least from our standpoint. The American population came to realize that their troops were not simply fighting the enemy – they were brutalizing him.

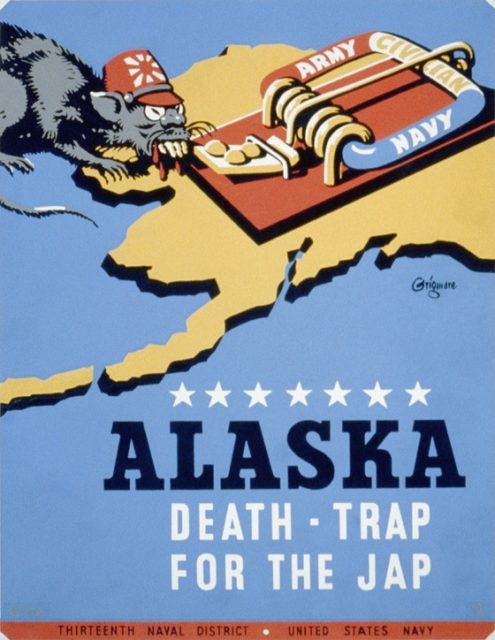

Already in 1942, rumors started spreading that the Americans were collecting so-called “war trophies” – ears, skulls, teeth, bones, and various other body parts from the dead Japanese. The Army superiors soon confirmed the rumors and issued an order for disciplinary action against those who committed such acts. But, to no avail.

Soon, the mainstream media picked up on this phenomenon – and did its best to romanticize it. In early 1943, a US Army’s weekly magazine, Yank, published a cartoon depicting the parents of a soldier receiving a pair of ears from their son. A year later, Life Magazine featured a full-page image of a young woman with a Japanese skull, with a tagline: “Arizona war worker writes her Navy boyfriend a thank-you note for the Jap skull he sent her.”

Numerous firsthand testimonies claim that the practice was widespread among the US troops. Historians claim that some 60 percent of Japanese soldiers killed in the Mariana Islands were missing their skulls. You’d rarely hear such horrifying news from other fronts. Not even German POWs and soldiers killed in combat suffered in this manner – and their regime is well known for the brutality it caused to the humanity. So, why the Japanese?

Between brutality and racism

The explanations for this phenomenon vary among the experts. Some insist that this was due to the extreme circumstances of war. But this common sense can’t explain why only some soldiers indulged in these practices, while others didn’t, let alone why they targeted primarily the Japanese. It’s pretty safe to assume that the war had been very nasty to everyone involved.

Others claim that the main reason was retaliation. According to this line of reasoning, the Japanese were guilty of starting this vicious spiral. There are reports of troops finding photographs of mutilated marines in conquered areas. There were even news reports of terrible atrocities committed by the Japanese, although at times fake.

Although this could account for a part of the puzzle, blind spots remain. There are numerous accounts of soldiers promising to their loved ones that they will bring these sorts of souvenirs back with them. The US wasn’t a society in which “trophy-taking” was a thing. These fellas still didn’t get the chance to become psychologically brutalized by war. They didn’t witness their comrades suffer in enemy’s hands. And it’s unlikely that one air raid in Hawaii turned them into such vicious creatures.

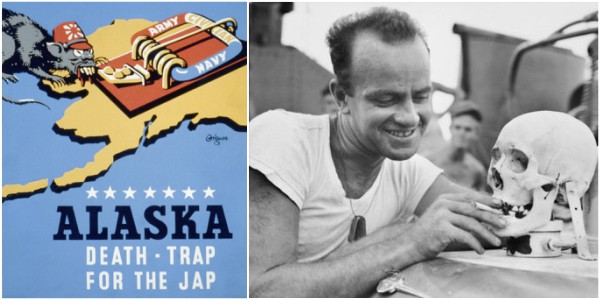

If we are to resolve this bizarre mystery, we need to look deeper under the surface. There we will find the underlying racism in American society, ignited and fueled by an openly racist media campaign. The press frequently labeled the Japanese as “yellow vermin”, or “living, snarling rats”. The war propaganda machine dehumanized the enemy. Some historians claim that the US soldiers often fought against the Japanese from the standpoint of the very ideology that had informed the Axis Powers – racism.

And this anti-Japanese racism had not been reserved for the poor and uneducated, prone to media manipulation, as is habitually considered. One example will suffice. In June 1944, Francis E. Walter, a Democratic Congressman, presented President Roosevelt with a letter-opener made out of a Japanese soldier’s arm. Newspapers reported that FDR commented along the lines of “this is the sort of gift I like to get”, and “there’ll be plenty more such gifts”.

The Japanese press, in turn, used this high-profile chance to portray Americans as “deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman”, absolving their own troops of similar actions. The US Army chiefs were furious. They knew that such publicity was exposing the American soldiers and POWs to trouble. Thus they even threatened those mutilating the Japanese with the death penalty. Weeks later, Roosevelt returned the gift.

Even though after the war, the American society “re-humanized” the Japanese, the vile practice of wartime mutilations continued – and remained a concern years later during the Vietnam War. As if the limits of combat brutalities are set in times of peace.