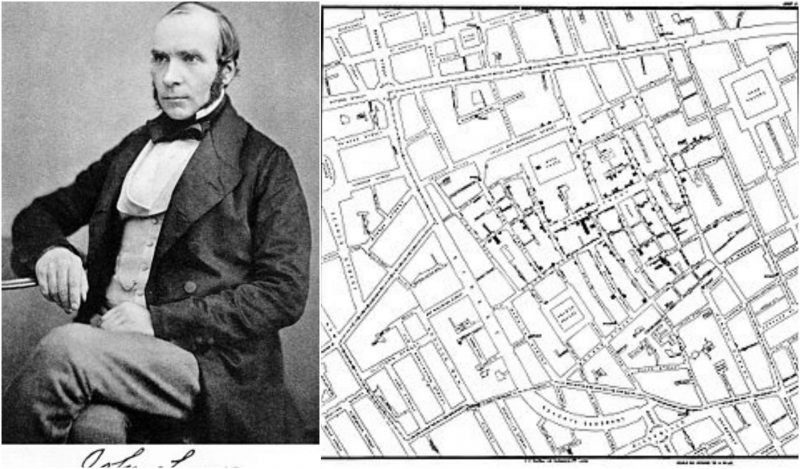

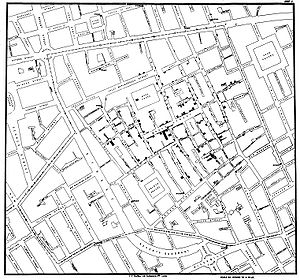

In 1854, there was an outbreak of cholera in the Soho district in London. Luckily, the physician John Snow was around at the time to investigate the case. He concluded that the reason for the spread of cholera wasn’t the air, but rather a contaminated water. This was one of the greatest discoveries of the century and led to a massive overhaul of the public health system, as well as much improved sanitation infrastructure. The discovery was also meaningful for doctor Snow, who is today known as one of the fathers of epidemiology.

In 1854, a few of London districts were suffering from cholera, but the worst outbreak was in Soho, where 127 people died in only three days. After only a month there were 500 deaths in the center of London, and people at the time mistakenly thought that the disease spread through “miasma”, a kind of bad air that was believed to rise from the soil at night. There were few people, Snow among them, who didn’t believe in the miasma theory, but they couldn’t find a way to prove otherwise. It would be five years until Lous Pasteur’s germ theory revolutionized the world of medicine, so no real alternative cause could be offered.

Snow had previously published a paper on Miasmatic theory, but he was at a loss to explain how and why Cholera only affected certain districts. So, he decided to investigate the outbreaks in London in an effort to find out the true cause of the disease.

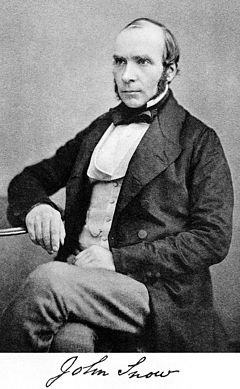

He began mapping the contaminated districts and came to the conclusion that the true culprit might be a polluted water. His next step was to map the water supply and pump system. He also visited the areas and talked to people in order to gain valuable anecdotal evidence. By connecting the residences of the deceased individuals to the water pumps that supplied them, his new theory seemed very logical.

Snow also noticed that the workers at a brewery near Broad Street were seemingly the only people who weren’t sick. He concluded it was because they were drinking so much beer that they weren’t drinking water.

When he published a paper with his new theory, other scientists were skeptical. But Reverend Henry Whitehead wasn’t. Even though he was a former believer in the miasma theory, he followed Snow’s article and even helped him in tracking the contamination to a faulty cesspool and the outbreak’s index case.

The Board of Health after investigated the 1854 outbreak of cholera and attributed it to “bad air,” but Snow’s theory began to gain traction in the following years, and thanks to him people gained a valuable new perspective of the illness, and how to protect themselves from it.