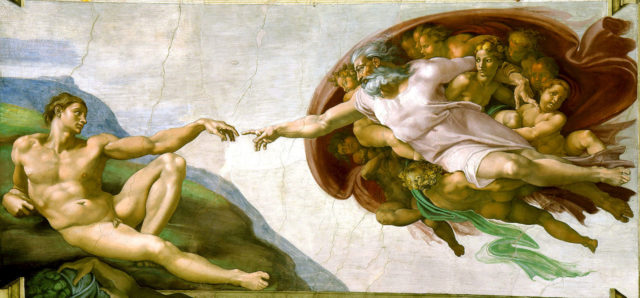

It is one of the greatest works of art in the world, portraying the history of the Catholic Church from the conception of man to the arrival of Christ. Yet the large and stunning painting sweeping across the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel might hold a feminist message that was overlooked by the religious regime that commissioned it. Michelangelo was the Renaissance master artist who spent four years creating the painting, which may contain hidden references to the female anatomy within the artwork.

The Golden Ratio (1.618) is thought to be a hidden mathematic formula inherent in all works of beauty. It can be discovered all around nature – in elephant tusks, hurricanes, and even within the galaxies. It as well commonly marks the symmetry of your hand to your forearm and also the distance between your three knuckles located on each finger. Presently, some scientists believe that Michelangelo deliberately utilized the Golden Ratio while painting The Creation of Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, to better his artwork. The most recent discovery proposes that the harmony and beauty established within the works of the acclaimed Italian Renaissance artist might not be solely based on his anatomical noesis.

This disregards the Catholic position of the time, which held the human body to be a divine mystery and prohibited portrayals of anatomy. Researchers allege they have found shapes within the vast painting which exhibit more than a transitory resemblance to female sexual organs. These comprise the eight ram skulls that are placed at regular points about the ceiling, detaching the nude figures of a female and male set. They seem to resemble the female reproductive organs – fallopian tubes, ovaries, and the uterus. The researchers have as well deliberated the arm of Eve as the form of a downward pointing triangle. This corresponds to the vessel or chalice, which is an infamous pagan sign for the female body and fertility.

It is argued that there are eight other displays of either the symbol for the masculine form, which is a pointing triangle, or the female pagan symbol. It is believed that Michelangelo might have done this as a way to undermine the Catholic Church and his patron, Pope Julius II. Michelangelo idolized everything about the teaching connected with the sacred feminine. This was because the power of women and their capability of creating life was held extremely sacred within ancient Jewish and pagan teachings.

It is recognized that Michelangelo was not eager to take the commission for the Sistine Chapel, especially as he considered that type of painting to be an inferior category of art. The tremendous painting within the Sistine Chapel is appraised as the pinnacle of Renaissance art.

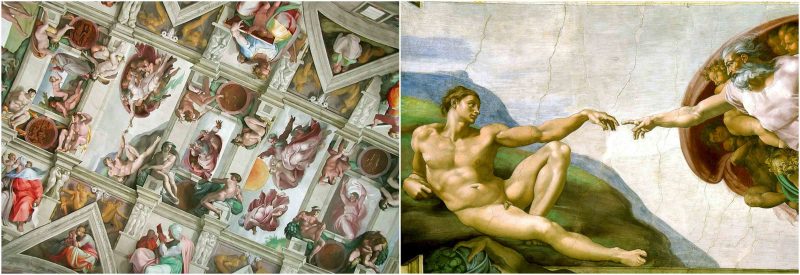

Michelangelo was authorized to paint the Sistine Chapel in the year 1507 by Pope Julius II, while also working on the Pope’s tomb. It took him four years to finish the project, and it stretches over 5,381 square feet. There are more than 300 figures that appear within the painting, with a total of nine scenes from the Book of Genesis located at the center.

On the arches supporting the ceiling are 12 women and men who prophesied the forthcoming of Jesus, identified as the Sibyls and Prophets. Simply looking at the precise detail has led several to pick out pictures that seem to be secret symbols, and codes that are hidden within the painting. Several of these symbols include eight triangles comprising groups wearing biblical clothes. Countless commentators believed the figures represent Jews throughout the duration of history waiting for the return of the Messiah.

Family scenes within the triangles about the ceiling display women in dominant standing, possibly another message from Michelangelo to the Catholic Church and their perspective of women. It as well points to other evident indications of his endeavor to overturn the male-dominated church.

For instance, countless women depicted within the painting are overly muscular, which might have been his attempt to display female strength. This was at a time when several theologians argued whether women even possessed souls. Yet it is not the first time experts have spotted anatomical representations within religious art.