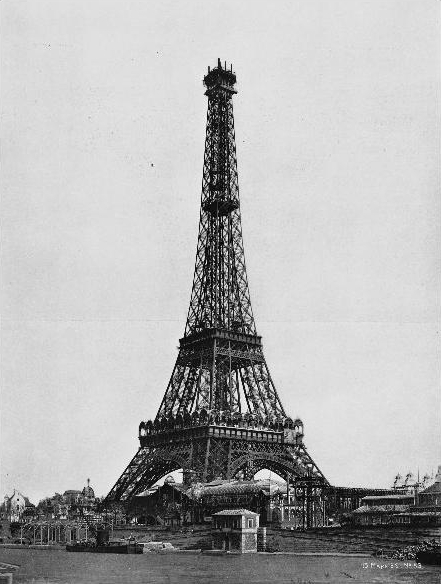

The year was 1925 and Victor Lustig was sitting in a hotel room in Paris, sipping his morning coffee while reading a depressing newspaper article about the Eiffel Tower. It seemed that the metallic structure was rusting and in need of expensive repairs and maintenance, but the government couldn’t afford money for its upkeep. The reporter’s article ended with the suggestion of selling the tower as a reasonable option.

Victor’s eyes lit up. He would sell it! Of course, the Eiffel Tower didn’t belong to him, but considering the fact that you’re reading about one of the world’s greatest con-men, real estate authorization was, in this case, just a minor detail. Victor cherished the action, the thrill, and the not getting caught. It was the zest of his criminalities.

According to Lustig’s unreliable biography, details as told in his prison interviews, he was born in Hostinné, a small town in Austria-Hungary, which is today’s Czech Republic. One of his scenarios described his family as the “poorest peasants in the town,” while another praised them as descended from royalty and his father as the mayor.

As a young boy, he was an excellent student, although he wasn’t focused on traditional academic subjects but on the study of people. He was extremely clever and took up languages quickly and, interestingly, the patterns of people’s behaviors that not many others noticed. He studied at a university in Paris and became fluent in Czech, English, German, and Italian. He was never an imposing person, but he learned at a young age that charm and poise were his greatest weapons.

The early 1900s marked the beginning of Lustig’s scamper up the criminal ladder. He started as a panhandler but soon evolved into a pickpocket, then burglar and street hustler. Gambling was one of his greatest passions at the time, including poker, blackjack, and anything that provided him with perfecting his card tricks. According to True Detective Mysteries magazine, he could make a deck of cards “do everything but talk.”

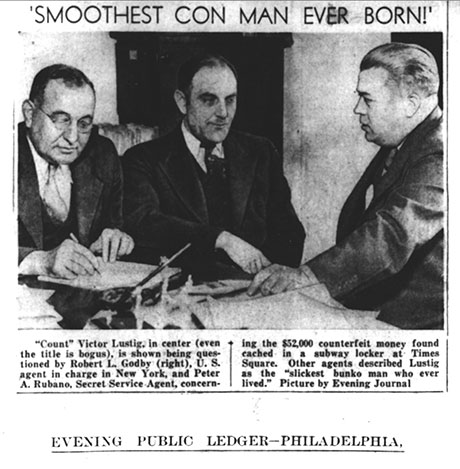

In Europe, Lustig’s acquaintances considered him a well-spoken, clever conversationalist. He was always elegantly dressed and gentlemanly, qualities that earned him the nickname “the Count.” He operated under many aliases, but he could always be distinguished by a 1.5-inch-long scar on his cheek, which he received from someone who wasn’t such a great admirer of his charms. This somber mark on Lustig face was the reason why later police would refer him as “the Scarred.”

When the roaring ’20s appeared, it became evident that big money was available in America and that was the place to be. Stories were told of people getting rich overnight. So, Lustig thought, where better to make money than aboard ocean liners packed with wealthy travelers? His first victims were the newly rich first-class passengers.

Using his charms, he dedicated himself to making small talk with wealthy businessmen. He sold them his so-called “money boxes” that, according to Victor, could print and copy $100 bills using radium. The price of these money boxes ranged from $20,000 to $30,000. He filled the machines with a few $100 replicas, which slowly emerged from the box as they were being printed. One bill was “printed” in about six hours and by the time two or three were done, Victor was long gone.

But this activity became too mundane for him, so he started to look for something more exciting. He soon found it–the aforementioned purchase of the Eiffel Tower, which seemed like a perfect contribution to his crime resume. First, he got himself a new fake ID. Next, he had false papers printed with the emblem of the government department in charge of public buildings. Getting down to work, he invited the top five iron-salvage companies in Paris to the Crillon Hotel, which was a popular place for formal gatherings, to meet the man in control of the Eiffel Tower.

He made a show of buttering up five company representatives, who all swallowed the story that the Eiffel Tower would have to be sold for scrap. Of course, this was a controversial purchase that required utmost discretion. Lustig picked out his victim: André Poisson, a man with low self-esteem who was anxious to make a name for himself in Paris.

When they met the next day, he confessed to have some doubts about the whole deal. The cunning Lustig put him at ease with a just-between-us story of being an underpaid government employee who entertained clients but needed some extra cash. Lustig offered to guarantee Poisson the (make believe) contract in return for lining his pocket a little. Poisson was sure that almost any government official was corrupt while no con man would ask for a bribe, so he took the bait, paying the bribe plus the offered price of the deal.

Next, Lustig was on a train to Vienna. A few days later, Poisson faced the fraud–the post, telegraph, and telephone companies ridiculed him when he asked when the tower would be dismantled. His embarrassment was so great that he refrained from reporting the case to the police in order to maintain his reputation in the city. Lustig realized that no news meant good news, so he returned to Paris and tried to repeat the whole process of “selling” the Eiffel Tower. However, the new victim checked a little further into the offer and found out it was a fraud. This time, the police were notified. They found the proceeds from the second sale as potential proof, but Lustig had already fled to America.

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our Today In History newsletter!

Across the Atlantic, Lustig returned to selling his money box. He used as many as 47 identities and managed to escape jail countless times. He went on making phony bills that, although initially passing smoothly through the bank counters, were soon tracked by the Secret Service who marked Lustig as wanted. His counterfeit cash operation was so huge that it threatened to become a serious issue for the American economy. The “Lustig money” came to an end when Lustig’s jealous girlfriend betrayed him to the Federal Agency as an act of revenge. He was finally caught in 1935 and sentenced to 20 years in Alcatraz Prison.