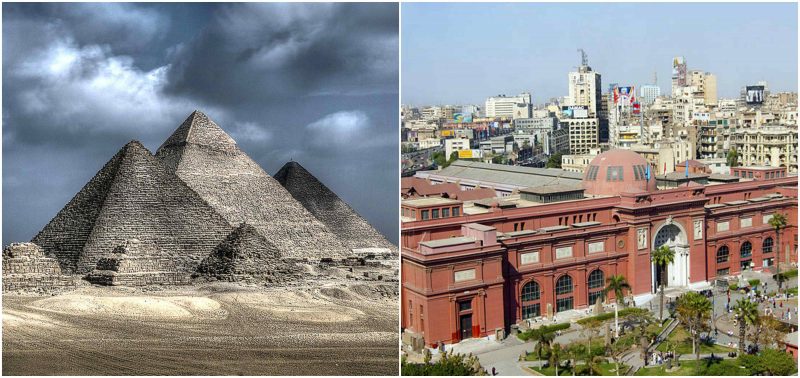

Egypt is not able to afford searches for ancient buried treasure because of its economic crisis, the antiquities minister has stated. With an economy that thrives from tourism, it has been hit hard since 2011 when the revolution that overthrew ruler Hosni Mubarak impacted several of Egypt’s famous historical locations. From the Valley of the Kings to the Giza pyramids, Egypt is currently suffering from a decline in foreign visitors.

Khaled al-Anani, Egypt’s antiquities minister, has said that over 20 museums have closed down since the January 25th Revolution, and they do not have the resources to run them anymore. The ministry is supposed to be self-sufficient, and does not receive funds from the budget of the state.

In 2012, the ministry produced 1.3 billion Egyptian pounds annually; by 2015, their income went down to 275 million pounds. Since they have to pay 80 million a month alone for salaries, that leaves 20 million pounds a month.

It is stated by al-Anani that with no revival in tourism, none of his the ministry’s new projects will have the desired effect. He has planned projects such as the introduction of a year-long museum, heritage site passes, and longer opening hours.

They have the museum Pyramid Complex of Unas, which was built for Pharaoh Unas, the ninth and the final king of the Fifth Dynasty in the middle of the 24th century BC. It has been closed since 1998 for fear of overcrowding, and al-Anani had reopened it this May.

Egypt has an idea to partially open the Grand Egyptian Museum. This location was planned for Ancient Egyptian artifacts and was to be the world’s biggest archaeological museum by 2017. This was made possible because Japan loaned $248 million to Egypt years ago.

The financial crisis has also affected excavation attempts, which have suffered a steep decline since the year 2011.

Some other issues are a lack of international law specialists at the ministry to aid in reclaiming Egyptian artifacts that were bootlegged to other countries. Other items were claimed by the country’s previous colonial rulers as a requirement for making a centralized database of antiquities in order to fight smuggling. These efforts have stalled at the museum since 2000.

Mr. al-Anani was assigned his job in March; the person who was in office before him supported British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeve’s theory of the secret chamber. He had faith that the lost burial site of Queen Nefertiti might be lying behind King Tut’s tomb.

Nefertiti had died in the 14th century BC, and was believed to be Tut’s stepmother. Being able to confirm her final resting place would be the most extraordinary Egyptian archaeological discovery of this century.

An examination of radar scans done on the location last November have unveiled the existence of two empty spaces behind two of the walls inside of King Tut’s chamber.

Previous minister Mamdouh al-Damaty stated in November that there was a 90 percent chance of something being behind the walls. Reeves has faith that the mausoleum was in the beginning occupied by Nefertiti, and that she has lain undisturbed behind a partition wall.

The most insignificant of cuts in the wall can damage any inner chamber that might have been sealed for several years. They intended to open the tomb, but only if the second radar scan showed a 100 percent proof that there was something in the empty space. However, further tests failed to yield conclusive evidence.