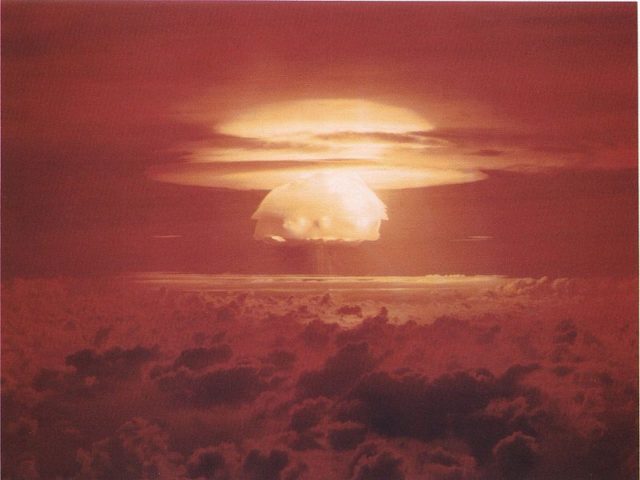

A Japanese trawler was caught up in the fallout of Castle Bravo nuclear test in 1954, killing its radioman; his last words were, “I pray that I am the last victim of an atomic or hydrogen bomb”. When Bravo was blown up, within a second it had formed a fireball almost four and a half miles wide. The fireball was seen on the Kwajalein atoll over 250 miles away. The blast left a crater 6,500 feet wide and 250 feet deep.

The mushroom cloud it produced reached a height of 47,000 feet, and it was seven miles wide within about one minute. In less than 10 minutes it had reached a height of 130,000 feet and 62 miles wide, and was growing at a rate of 100 meters per second.

The cloud contaminated more than 7,000 square miles of the surrounding Pacific Ocean, including several small islands like Utirik, Rongelap, and Rongerik.

Castle Bravo, in terms of TNT tonnage equivalence, was about 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during WWII. Bravo is the fifth largest nuclear blast in history, exceeded only by the Soviet tests of Tsar Bomba at 50 megatons, Test 219 at 24.2 megaton, and two other 20 megaton Soviet tests in 1962 at Novaya Zemlya. The designers of the Castle Bravo bomb predicted a yield of 5 megatons, so the 15 megatons it actually produced was three times more than expected. The cause was a higher yield was a theoretical error made by the designers of the device at Los Alamos National Laboratory. They thought that lithium-6 isotope was the only reactive one of the element’s isotopes. Lithium-7, which made up 60% of the bomb’s lithium content, was thought to be inert. in fact, it also reacted with the fission of the blast, producing a much stronger explosion that was calculated.

The fission reactions of the natural uranium casing were fairly dirty, which produced a large amount of fallout. The fallout, along with the larger than expected yield and also a major wind-shift, caused some very dangerous consequences. The film Operation Castle, which was de-classified, showed task force commander Major General Percy Clarkson pointing to a picture showing that the wind shift was still within range of the “acceptable fallout”, though only barely.

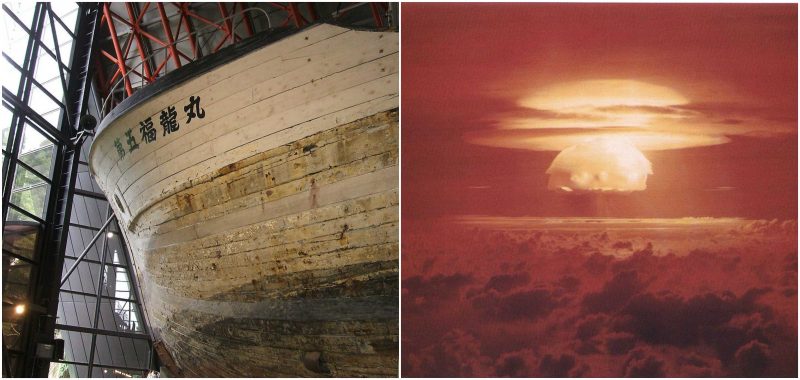

Daigo Fukuryū Maru (Lucky Dragon No.5), a Japanese fishing boat, came in direct contact with the fallout, which made many of the crew very sick; one died of a secondary infection.

Because of this, it caused an international incident and stirred up the Japanese and their concerns over radiation, as Japanese citizens were once again adversely affected by U.S. nuclear weapons.

The U.S.’ official position had been the growth in strength of atomic bombs does not go hand-in-hand with the equivalent growth in radioactivity released into the atmosphere.

Japanese scientists that had collected samples from the fishing vessel disagreed with this. Sir Joseph Rotblat, who worked at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, showed that the contamination that was caused by the fallout from the test was much greater than stated officially.

Rotblat was able to show that the bomb had three stages and showed that the fission phase at the end of the blast increased the amount of radioactivity by a 1,000. The paper that Rotblat wrote was snatched up by the media and the outcry in Japan reached such a level that diplomatic relations became strained and the incident was even called “a second Hiroshima”.

Even so, U.S. and Japanese governments quickly reached a settlement, with the transfer to Japan of $15,300,000 for compensation which was split, with the remaining survivors getting about $5,500 each in 1954 (or about $48,900 in 2016). Both sides also agreed the victims would not be given Hibakusha status.

The same as the “Hibakusha”, survivors of atomic blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, the Lucky Dragon crew were also stigmatised because of the Japanese public’s fear of those exposed to radiation, which people thought was contagious. Those people tried to remain quiet about their exposure for several decades, starting with their discharges from the hospitals. Several of the crew had to move from their homes to get a fresh start.

Susumu Misaki, 86, was a former crew member that opened a tofu shop after the incident.

Matashichi Oishi, who was 20 at the time of the blast, is reported to have licked the mysterious fallout substance that fell on his ship in March, 1954, as a taste test to determine its properties, is 82. After he was exposed, he left his hometown to start a dry cleaning business. Starting in the 1980s, he frequently gave talks advocating nuclear disarmament. He published a book in 2011 titled, “The Day the Sun Rose in the West: The Lucky Dragon and I.”