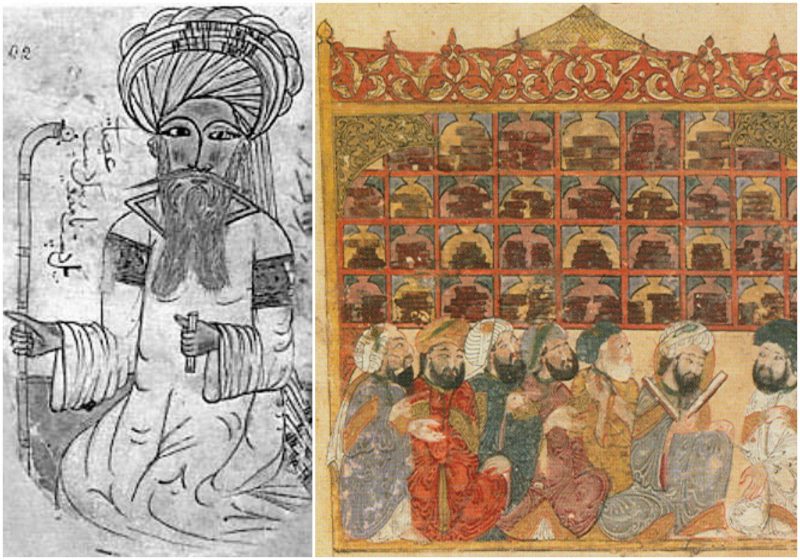

The cultural and scientific enlightenment fostered by the Islamic Golden Age during the Abbasid Caliphate undoubtedly propelled mankind’s progress during the High Middle Ages. Contributing to various scientific fields, many thinkers and philosophers such as Al-Farabi, Al-Kindi, Rhazez, and others have cemented their names in the history of science. As for Ibn Sina, his work and research are arguably the most revered.

Also known as Avicenna, Ibn Sina was a Persian polymath with contributions in medicine, psychology, geology, physics, astronomy (he was the first to propose that Venus was closer to the Sun than the Earth), and of course, philosophy. A prominent thinker and empiricist, in contrast with his scientific penchant for knowledge, he was also a poet and an Islamic theologian.

Records and historical facts about his life are hard to pin down, as there exists only one known autobiography about him, written by one of his students, al-Jūzjānī. He was born in a village near Bukhara (modern-day Uzbekistan) in 980 CE, most likely in August.

Because of his father’s position as a governor and a respected scholar, Ibn Sina received a quality education and upbringing. The young genius could memorize the Quran at the age of 10 and had a thirst for unconventional knowledge for his age. At times, he prayed in mosques, when challenged with difficult texts and ideas.

One of his many tutors, Nātilī, had the honor to teach elementary logic to Ibn Sina. However, his teachings were obsolete, since the young thinker was rapidly grasping advanced ideas and was already entering new fields of knowledge.

Undertaking a tremendous task of studying the works of Aristotle on his own, he gained a methodical approach to the sciences which, in return, aided his logical viewpoint. He had difficulty at fist, but once he read Al-Farabi’s commentary on the work, he quickly understood Aristotle’s “Metaphysics”. Contrary to popular belief, he was not the first to introduce Aristotelian philosophy to the Middle East, but he was by far the most distinguished.

Ibn Sina favored medicine and anatomy over the rigid field of mathematics and logic; thus he began studying medicine at the age of 16 and became a skilled physician by 18. By 997 CE, Ibn Sina healed the local emir, Nuh II, from a life-threatening illness and was promptly appointed as the emir’s personal doctor. The respected position that Ibn Sina gained from this rather heroic deed allowed him valuable access to the Sāmānid royal library, consequently opening new doors of knowledge. Ibn Sina never required payment from his patients, as the practice of curing and mending their wounds was payment enough for the curious physician.

By his 20s, Ibn Sina undertook writing his ideas, penning many books about astronomy, medicine, philosophy, mathematics, music, poetry, and philology.

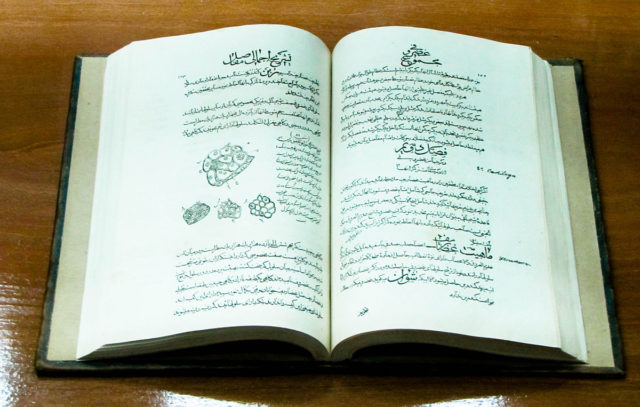

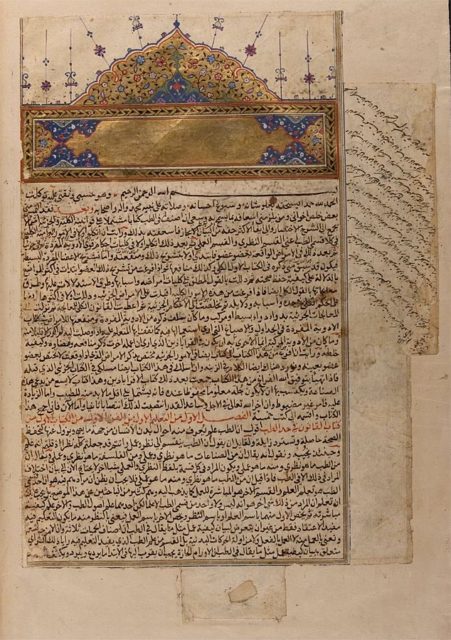

One of his 450 written books (about 240 are remaining) includes Al-Qanun, or “the Canon”, a large encyclopedia of medicine that holds the entire medical knowledge at that time. By all means, it has been used by scholars as a fundamental textbook until 1650, even though being put through some criticism by the Renaissance.

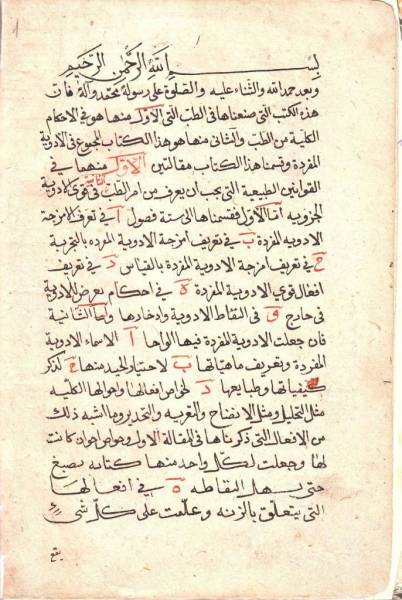

Equally important is his philosophical book, The Book of Healing (Kitāb al-shifā). Ibn Sina’s most important work and a milestone in the history of science. The book is divided into categories about mathematics, science, logic and metaphysics. It is an attempt to generalize common knowledge and sort the different aspects of knowledge and science into acesssible themes.

General logic was viewed by Avicenna as the main tool for philosophy. On the other hand, Avicenna’s flaw was his belief of “celestial hierarchy,” mentioning God as a key factor. While he was generally within the tradition of al-Fārābī and al-Kindī, he clearly dissociated himself from the Peripatetic school of Baghdad. Instead, he was using the concepts of the Platonic doctrines, as well as the ideas of the Stoics.

There are speculations as to how Avicenna died. One theory is that when he served Alā al-Dawla (the Kakuyid military commander) on his march to Hamadan, a slave poisoned him with opium. Others claim that Ibn Sina died as a result of excess herbal medications and overeating, consequently weakening his digestive system. His last years were nevertheless withering.

He could barely stand because of severe colic, perhaps caused by overeating. Refusing to take the regimen of medicine required for his cure, he resigned himself to his fate. He stated that: “I prefer a short life with width to a narrow one with length”. He died in June 1037, in his fifty-eighth year and was buried in Hamadan, Iran. Although decrepit in the early years, Ibn Sina’s tomb in Hamadan is now refurbished and restored. A historical museum and mausoleum, it also has a library that contains 8,000 volumes. The tomb depicts the life and times of Ibn Sina and is a frequently visited location for tourists in the region.

Ibn Sina’s life was rather fulfilling, despite his scientific and political duties. He was also known for his love of life, strong drink, and many women. His wisdom and worldview won him many friends and enemies as well. Either way, Ibn Sina is remembered as one of the greatest polymaths of all time.