When one thinks of ghost towns, an image of the American West comes to mind – not America’s Dairyland state.

Wisconsin, in the Midwest United States located along the shores of Lake Michigan, is the nation’s largest producer of dairy products, especially cheese. It is also noted for beer brewing and Harley Davidson motorcycles.

In the early days of new settlement from 1836 to the end of the Civil War in 1865, the southern area of the Wisconsin Territory saw small European and even a few African settlements pop up near locations that followed the railroad or near areas where water and trade were plentiful.

As time went on and Wisconsin moved closer to becoming organized enough to apply for statehood, these small settlements disappeared.

Historian and New Glarus, Wisconsin, native Kim Tschudy has been working on finding out the history of these lost towns and their inhabitants. He is also the author of several books including Greene County , a history of Greene County in which he discusses some of Wisconsin’s ghost towns and The Swiss of New Glarus, a look at the Swiss immigrants who were the early dairy farmers of Wisconsin. Both books have a 5-star rating on Amazon.com. He also has published photo archives relating to the B&O Railroad and the Illinois Central Railroad. Additionally, Tschudy has given lectures in which he discusses excerpts from his books which have been recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

Some of the towns Tschundy has discussed include Voree, Gratiot’s Grove and Cheyenne Valley, as well as others and how these communities lived and died in the 19th century.

Lafayette County’s Gratiot’s Grove, for example, came to be as a lead mining town, but only existed until the lead supply ran out, much as western ghost towns met their fate. Gratiot’s Grove was named for Colonel Henry Gratiot, an early pioneer born in the Louisiana Territory. Gratiot moved to the north in the early 1800s due to his opposition to slavery, and eventually settled in Illinois. Upon hearing of the discovery of lead ore in Wisconsin he and a brother bought mine rights from the Winnebago Indians in 1826. There they built a successful lead mining and smelting business with six furnaces employing sixty Frenchmen. After the mines had ceased to produce, he remained in the area and became a gentleman farmer. Gratiot was friendly with the Winnebago and was instrumental in establishing treaties between the Indians and the United States Government. He also spent the remainder of his life traveling back and forth between Wisconsin and Washington D.C. in attempts to convince the government officials to honor the conditions of the treaties. His home, the second oldest in the state, is still standing and has recently been renovated into a Bed and Breakfast.

Cheyenne Valley in Vernon County, and Pleasant Ridge in Grant County were largely populated by escaped or freed slaves and also previous plantation owners who had developed close relationships with the former slaves. Cheyenne Valley was the largest African American settlement in Wisconsin during the 19th century due to Wisconsin’s refusal to adhere to the Fugitive Slave Act established in 1850. Many of these former slaves owned large tracts of land and became successful farmers. Cheyenne Valley also boasted some of Wisconsin’s first integrated schools and churches. As a former resident of the area stated, “Everybody was concerned about their neighbor. We didn’t even know we were integrated – we just didn’t care about color”.

Sinipee, a former lead mining town in Grant County was formed as a port community on the banks of the Mississippi River by the Sinnipee Company in 1835. Unfortunately, the town was flooded in 1840, and a subsequent deadly fever caused most of the town’s surviving residents to move away.

The town of Ulao in Ozaukee County, near the present town of Grafton, was the boyhood home of Charles Julius Guiteau, the assassin of President James A Garfield. The town was founded in 1847 by James T. Gifford, Guiteau’s uncle, from Elgin, Illinois. The plank road he ordered to be constructed to transport logs from the town to the Wisconsin River eventually became what we now know as Highway 60.

Zarahemla, near Yellowstone Lake State Park, was founded by Mormons as was Voree in Walworth County. James J. Strang, the self-appointed successor to the founder of the Mormon Church Joseph Smith Jr. founded Voree for Mormons who were not interested in following the teachings of Brigham Young. According to Tschudy, “There on 1850, Strang was crowned the king [of the town]. He wore a discarded Shakespeare actor’s red robe and a crown for his coronation. Shortly thereafter, Strang proclaimed that the Lord had commanded him to institute polygamy, which caused a great uproar. Strang’s despotic rule was despised and in the summer of 1856, two of his followers shot and killed him.”

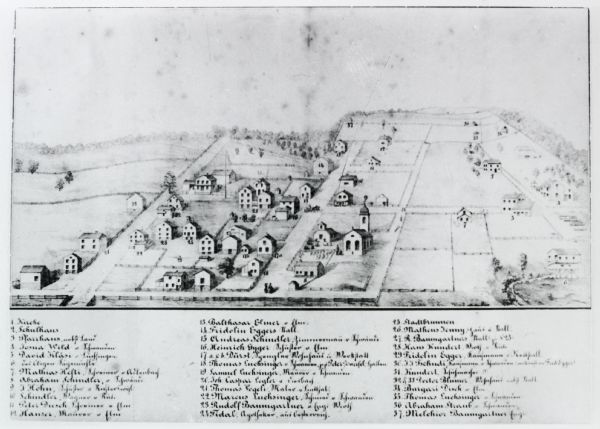

Tschudy’s favorite ghost town is Centerville, in Green County. In his lecture, he remarked, “What happened was the town was laid out and speculators that laid out the town had these beautiful drawings of Centerville. They went to Milwaukee, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland and Philadelphia, selling these lots in this beautiful mecca in southern Wisconsin. These people showed up to claim their lots and the only thing they found were the red surveyors’ stakes. There was never a nail driven there, and the speculators were long gone.”

His explanation as to why these towns were eventually abandoned is as follows: “New Diggings [in Lafayette County], like so many towns fell victim to the loss of the natural resources, which is a typical strain with almost all of the towns…. Either it was a natural resource boom that they could take and use, or it was the loss of a railroad or the railroad not coming to their town.”

In addition, check this awesome video about Ghost Towns:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aHJAoR0Jw58