In the post town of Beckenham, in the London Borough of Bromley, England, 270 acres of woodland, fields, gardens, and well-kept lawns surround Bethlem Royal Hospital, the oldest mental health institution in the world.

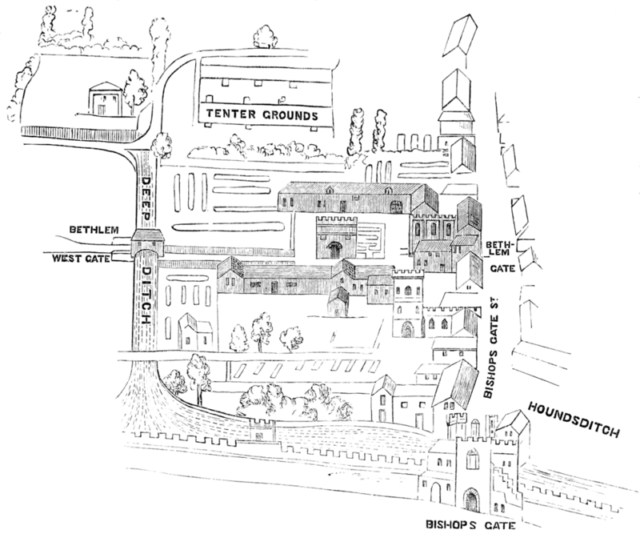

Originally built over a sewer in 1247 as a priory to collect alms, it was called “The Priory of the New Order of St. Mary of Bethlehem”.

The monks began bringing those who suffered from mental illness to the Priory to care for them. Knowing little of mental illness, the monks felt that isolation and harsh treatment would benefit the inmates in a kind of “tough love” manner and began a trend that would last for over 500 years.

Due to the harsh treatment, unruly inmates, and frequent sewage backups the institution was dubbed “Bedlam”. If one were to look up the word in the dictionary, it would be defined as “a place, scene, or state of uproar and confusion” with an obsolete meaning of “madman or lunatic”. And that it was.

Not a lot is known of the treatments these people had to endure, but locks, chains, and manacles were all found at Bethlem.

William Black’s 1811 “Dissertation on Insanity” described the asylum in these words: “In Bedlam, the strait waistcoat when necessary and occasional purgatives are the principal remedies. Nature, time, regimen, confinement, and seclusion from relations are the principal auxiliaries.”

Regrettably, people that suffered from epilepsy, learning disabilities, and simple treatable mental illnesses such as mild OCD and situational depression were stuffed into overcrowded rooms with those who suffered from schizophrenia, paranoia, and delusions.

At the time, people like Helen Keller, Vincent Van Gogh, and Ernest Hemingway could easily have been locked up and subjected to torture.

The original Bethlem building was destroyed in the London fire of 1666 and a new building was built in Moorfields. It was larger and more attractive than the previous building, but only on the outside.

Beautiful new gardens and a stone wall were built around the asylum to encourage visitors, but inside it was business as usual. Dangerous inmates were not separated from those who, in reality, should not have been there. Few doctors were on staff, leaving the nurses and orderlies to deal with violent, angry inmates.

In the late 1600s, Bethlem became a sort of tourist attraction, with visitors allowed to view the patients and their treatment in what some have called a “human zoo”.

According to Caroline Smith, Education and Outreach Officer at Bethlem’s Museum of the Mind, “People were invited in not for malicious voyeurism, but because the hospital’s resources were stretched so thinly that it needed to collect charitable donations to keep it going. In that time, there was no way of the public knowing what work the hospital did without seeing it for themselves.

Like a lot of the practices that went on in Bethlem that now seem deplorable, they were done largely with the best of intentions, and using only the knowledge of mental illness at the time.”

A new building for the asylum was completed in the 1830s in Southwark, which could accommodate 300 people and had separate wings for men and women. Even though knowledge of mental illness was improving, inmates at Bethlem were still brutally mistreated.

Now in its current site since 1930, Bethlem has outlasted the majority of asylums, which were common at one time. New attitudes and better treatments have replaced the horrors of early mental health treatment, but understanding of mental illness still has a long way to go, both in treatment procedures and associated stigma.

It is believed that in Great Britain and the United States, one in every four people suffer from some sort of mental illness.

It may be situational, or it may be chronic, but most don’t even realize they are afflicted, owing to the fact that they believe that the way they feel is normal, when in fact, they could live much happier and productive lives if they were open to receiving treatment.

As Mike Jay, author of This Way Madness Lies, has remarked, “Mental health affects everybody, but nobody fully understands it.”

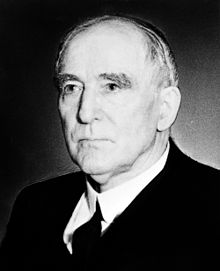

Sir Henry Solomon Wellcome (1853–1936) was an American pharmacist, philanthropist, and collector. He amassed a huge collection of medical devices and health-related information from all over the world.

The Wellcome collection and library is now housed in a museum in London, enabling healthcare workers and the general public to study medical techniques and procedures used throughout history. A new attraction, Bedlam: The Asylum and Beyond, is set to open this fall to document the history of asylums and the changing beliefs and attitudes regarding mental health.

“It’s an enormous subject, madness, and mental health,” remarked co-curator Mike Jay. “I appreciated that it if I wanted to look at the whole topic, I’d need some focus, and it occurred to me that Bethlem was the perfect way to frame it. I could tell pretty much the entire story by studying the successive versions of this one, still existing place.”

Among the items found in the exhibit are the original blueprint plans, artwork created by inmates, and personal recollections of inmates and hospital workers. Those looking for violent restraints, lobotomy machines, and other archaic instruments will be disappointed.

“The experience isn’t meant to perpetuate the ‘chamber of horrors’ idea people might have about asylums,” commented Jay. “In having the photographs, it’s hoped we can show that they were made with care and precision for the benefit of the patients – not necessarily to harm.

Each era at Bethlem began with great optimism but ended in failures, earning that reputation for gloomy neglect. We want to show the importance of that perspective.”

Co-curator, Barbara Rodriguez Muñoz, is quoted as saying, “The original concept of the asylum was a place for care and protection, and we are looking again at that, arguing whether the necessity for that space now is one that’s physical, figurative or perhaps even online.”

Jay and Muñoz are also offering alternative historical models for consideration by the public, including the town of Geel, Belgium, in which locals have incorporated the mentally ill into their families and helped them relate to society in a more gentle and humane fashion.

Jay said, “When people come here, we want them to feel that same sense of sanctuary that the asylum was intended to provide. Seeing the installations and objects, hopefully, they’ll feel more comfortable talking about mental health and consider what society’s best responses should be.

We want ‘asylum’, be that through ‘mindfulness’ or otherwise, but there’s a perception that the physical space belongs to the past. And how the future looks is a conversation we want to provoke; there is no right or wrong answer.”