The tunnels of Củ Chi are an immense network of connecting underground passages located in the Củ Chi District of Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), Vietnam, and are part of a much larger network of tunnels that underlie much of the country.

The tunnels were built over a period of 25 years that began sometime in the late 1940s, during their war of independence from French colonial authority.

The Chu Chi Tunnels were also utilized and expanded during the American-Vietnamese War by incorporating effective air filtration systems.

The tunnel systems were of great importance to the Viet Cong in their resistance against the American forces and played a major role in North Vietnam winning the war.

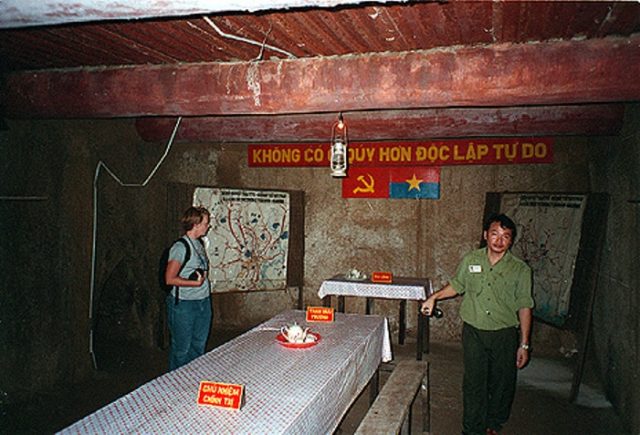

The tunnels were used by Viet Cong guerrillas as hiding spots during combat, as well as serving as communication and supply routes, hospitals, weapon caches, and food and living quarters for numerous North Vietnamese fighters.

The historical site comprises more than 120km of underground tunnels with living areas, kitchens, storage facilities, armories, hospitals, and command centers.

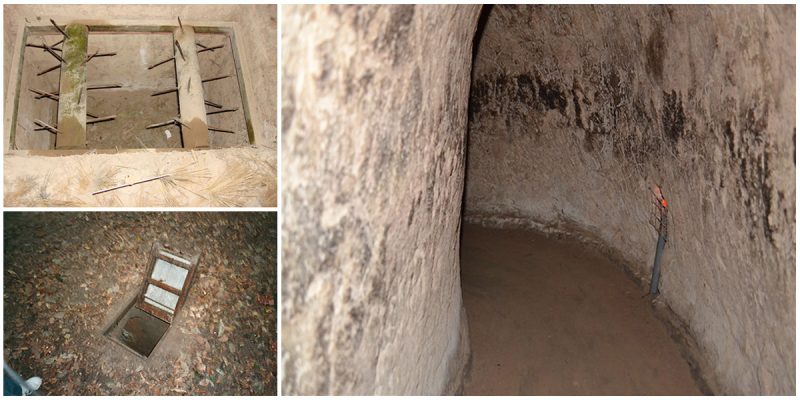

Most of the time, soldiers would spend the day in the tunnels working or resting and come out only at night to scavenge for supplies, tend their crops, or engage the enemy in battle. The tunnels were often rigged with explosive booby traps or punji stake pits.

Throughout the course of the war, the tunnels in and around Củ Chi proved to be a source of frustration for the U.S. military. The Viet Cong had been so well rooted in the area by 1965 that they were in the unique position of being able to dictate where and when battles would take place.

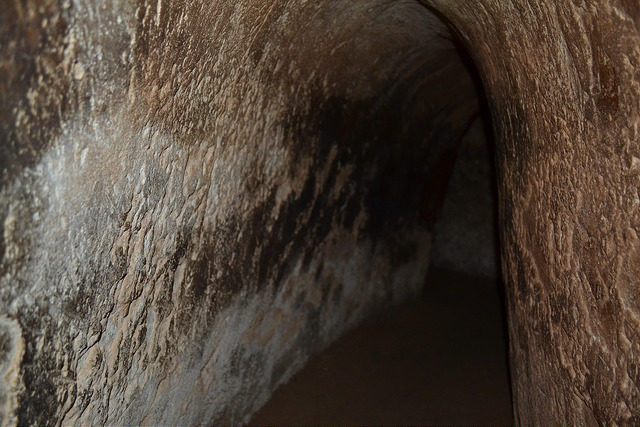

As the United States relied heavily on aerial bombing, North Vietnamese, and VC troops went underground in order to survive and continue their guerrilla tactics against the much better-supplied enemy. The US and Australian forces tried a variety of methods to detect and infiltrate the tunnels, but all were met with failure.

The clever design of the tunnels, along with the strategic use of trap doors and air filtration systems, rendered American technology ineffective.

To combat these guerrilla tactics, the US army began sending men called ‘tunnel rats’ down into the tunnels. The job of a tunnel rat was fraught with immense dangers.

These specialists, armed only with a gun, a knife, a flashlight and a piece of string, would spend hours navigating the cramped, dark tunnels, cautiously looking ahead for booby traps and scouting for enemy troops.

The light from the battery powered lamp wasn’t enough to pierce the darkness inside the tunnels, and there was no room to turn around and retreat. The tunnel rats, who were often involved in underground fire-fights, sustained appallingly high casualty rates.

By helping to covertly move supplies and house troops, the tunnels of Củ Chi allowed North Vietnamese fighters in their area of South Vietnam to survive, help prolong the war and increase American costs and casualties until their eventual withdrawal in 1972, and the final defeat of South Vietnam in 1975.

The 120-km long complex of tunnels at Cu Chi has since been preserved and turned into a war memorial park which offers a sneak-peek into the underground life of Vietnamese soldiers back in 1948.