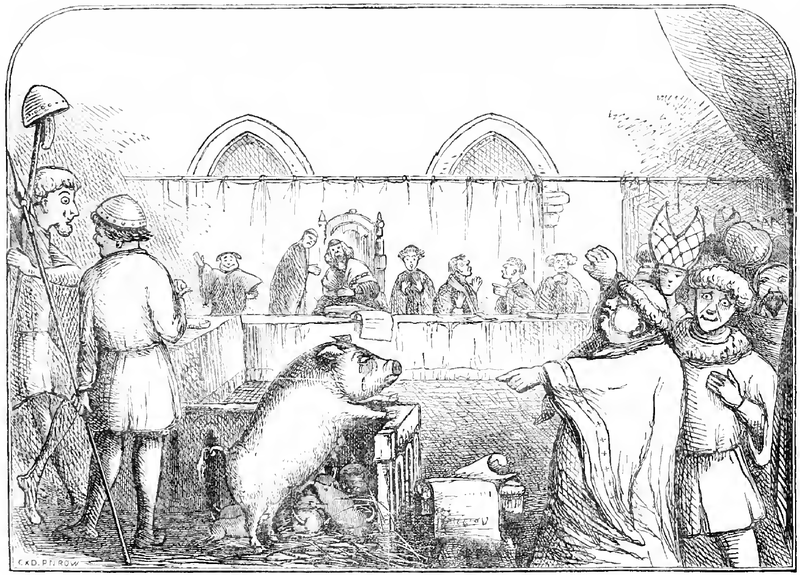

Throughout the middle-ages in Europe animals were, as it turns out, tried for human crimes. Animals were arraigned in court on charges ranging from murder to obscenity.

Pigs, dogs, cows, rats and even flies and caterpillars were arraigned in court with full ceremony. They would call witnesses and evidence were heard on both sides. They would grant a form of legal aid, a lawyer to the animal that was accused in order to conduct the animal’s defense.

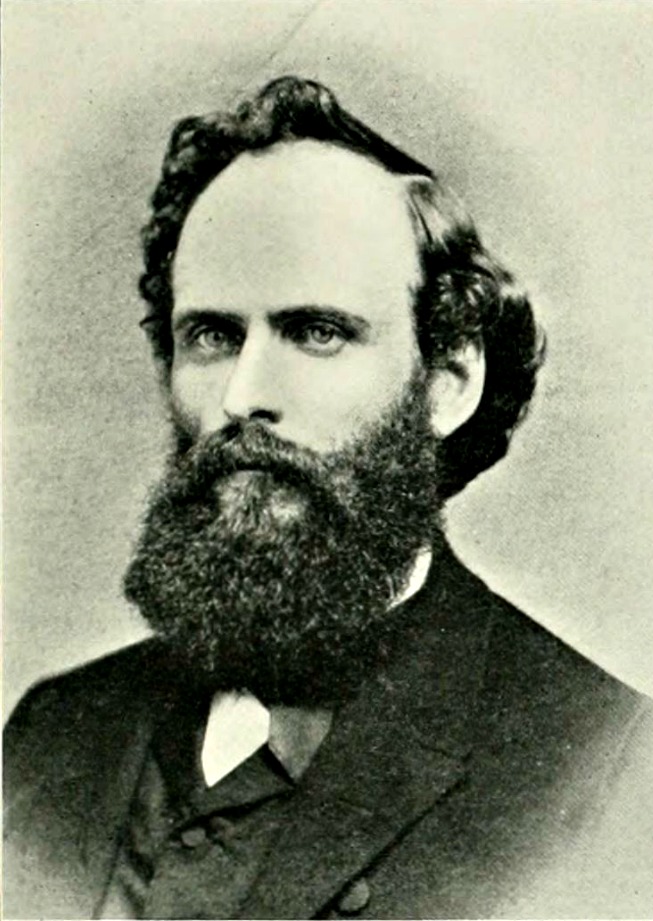

As it’s said in Edward Payson Evans’s book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals in 1266 a pig was accused of actually eating a human being. After a trial that was held the pig was found guilty and sentenced – by the monks of Sainte Genevieve – to a death by public burning.

The execution took place in the French village of Fontenay-aux-Roses.

Another case happened in 14th-century France when a young pig was arrested for attacking a child’s face which eventually died because of the attack. The pig was arrested for the killing, it was taken to prison just like humans accused of murderous acts and then stood trial in court.

There is a receipt for January 9, 1386, in which an executioner of Falaise, France acknowledges payment of ten sous and ten deniers for an execution. This was a special type of execution. The receipt reads:

“For his efforts and salary for having dragged and then hanged at the [place of] Justice in Falaise a sow of approximately three years of age who had eaten the face of the child of Jonnet le Macon, who was in his crib & who was approximately three months old, in such a way that the said infant died from [the injuries], and [an additional] ten s. tournoise for a new glove when the Hangman performed the said execution: this receipt is given to Regnaud Rigaut, Vicomte de Falaise; the Hangman declares that he is well satisfied with this sum and that he makes no further claims on the King our Sire and the said Vicomte.”

Evans’s book details more than two hundred such cases: sparrows being prosecuted for chattering in Church, a pig executed for stealing a communion wafer, a cock burnt at the stake for laying an egg.

One of the most amusing cases of the trial of a domestic animal was that of a sow together with her six pigs at Savignysur-Etang, in Bourgogne, France, in January 1457. The charge against her was murdering and partly devouring an infant.

The sow was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging, though her offspring, partly because of their youth and innocence and the fact that their mother had set them a bad example, but chiefly because proof of their complicity was not forthcoming, were pardoned.

For an animal found guilty, the penalty was dire. The Normandy pig, depicted in the frontispiece of the Evans book, was charged with having torn the face and arms of a baby in its cradle.

The pig was sentenced to be “mangled and maimed in the head forelegs”, and then dressed up in a jacket and breeches to be hung from a gallows in the market square.

Dressed for the occasion, the pig was wearing the clothes of a man:

“…As if to make the travesty of justice complete, the sow was dressed in man’s clothes and executed on the public square near the city-hall … The executioner was provided with new gloves in order that he might come from the discharge of his duty, metaphorically at least, with clean hands, thus indicating that, as a minister of justice, he incurred no guilt in shedding blood.” (Evans, page 140.)

Everyone connected with the trials and executions of animals was paid for his job.