One man deeply intrigued by the wonders of the wind saw himself using it so he could fly. Flying was his dream, and he craved for it more than anything. He was the son of a proclaimed mathematician whose father pushed him toward military service, seeing it as the best way to live an honorable life. However, his strong desire to create inventions and inventive spirit drove him elsewhere, to the skies.

His story and lifetime achievement can serve as the best example of what might happen if one only chooses to listen to his inner voice and chase his dreams. He is now one of the most respected aviators, and by some considered the man who brought jet plane technology to humanity.

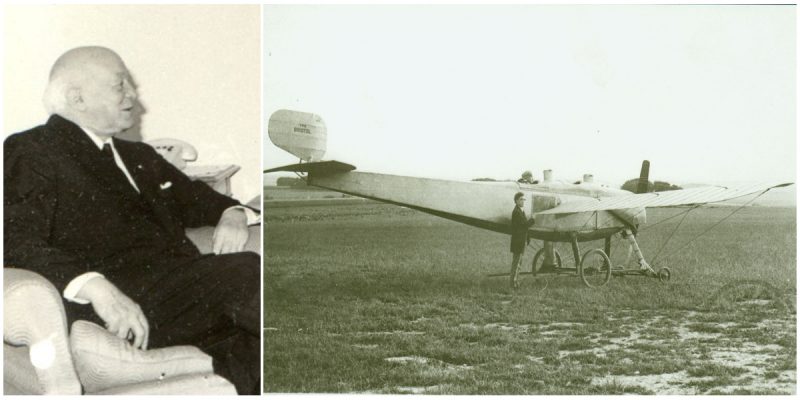

His name was Henri Marie Coandă. According to his claims, as well as many others who wrote about him in their scientific papers, he made his first flight in a highly original odd-looking jet plane on December 10, 1910.

But let us start at the beginning. Born in Bucharest on June 7, 1886, Henri Coandă was the second-born son in a large family of five brothers and two sisters. Their father, Constantin M. Coanda, was a distinguished Romanian soldier who later started teaching mathematics in Bucharest, at the National School of Bridges and Roads.

Following his father’s wishes, Henri finished his military education with high honors, earning the rank of artillery officer. However, his strong desire to fly and deep fascination for airplanes emerging at the dawn of the 19th century, as well as the technology behind their ability to travel the skies, sending his dreams far from the army life.

Knowing what had to be done, he soon dropped from the ranks and set himself on course to pursue a life in flight technology advancement.

By 1909, Henri Coandă had finished his studies. He attended the technical university of Berlin, Technische Hochschule in Charlottenburg, as well as a two-year study program at the Science University of Liege, which is part of the Electrical Institute in Montefiore. He graduated with the highest of honors and top of his class at the Superior Aeronautical School in Paris, now known as ISAE-SUPAERO (École Nationale Supérieure de l’Aéronautique et de l’Espace).

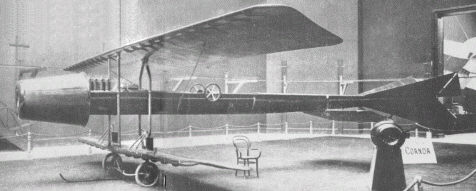

It took less than a year and the well-equipped workshop of Gianni Caproni, another aviator Coandă befriended in Paris, for this new graduate and fresh aeronautical engineer to construct the “Coanda-1910,” the aircraft for which he is most remembered.

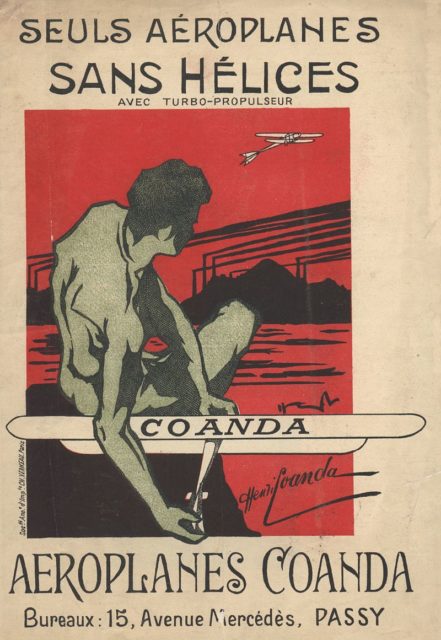

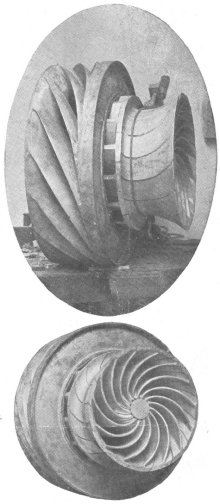

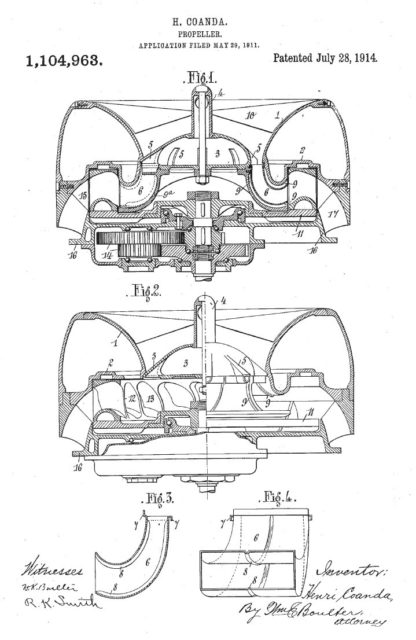

The plane was ready just in time to be presented at the Second International Aeronautical Exhibition which took place from October 5 to November 2, 1910, in Paris. It was revolutionary in so many ways. First and foremost, it didn’t have a propeller, which almost instantly got everyone’s attention. Instead, his plane was equipped with an inverted flower pot-shaped front, filled with built-in rotating blades arranged in a swirl pattern inside. Secondly, its design held so many novelties that his aircraft was placed in a separate gallery, completely secluded from other examples.

One of its many traits considered as “firsts” included the design of the wings. These were composed with steel leading edges rather than wood, adjustable slats on the forward edge to enhance lift, and the wing profile had a strong, solid chamber. In addition to that, the two wings on each side were of different lengths and sizes, with the upper one set slightly ahead of the lower wing, which was smaller. According to him, this would reduce the aerodynamic interference between the two surfaces. Due to the fact that the same principle was reinvented and applied in Fokker, Breguet, and Poetz aircraft nearly a decade later, it was probably seen as a great improvement by many others as well. This design is now termed Sesquiplan.

However, the most important innovation of them all and a real revelation for that time was the engine, labeled the turbo-propulseur. According to an article published in the journal La Technique Aeronautique back on December 1, 1910, the heart of the machine was the internal turbine screw, powered by a regular four-cylinder, 50-horsepower Clerget engine, built by Pierre Clerget. This engine was utilized in order to turn the rotating blades and start sucking in air through the turbine while “the heat of the exhausting gases…exited…at the rear, driving the plane forward by reaction propulsion”, as explained in the journal.

However, as much as the jet engine was impressive and the plane a real beauty to behold, no one actually believed it could fly. Even La Technique Aeronautique was skeptical that the engine could provide enough thrust to fly the plane. For instance, one reporter from the journal addressing the issue wrote, “In the absence of definitive trials, permitting the precise yield of this machine, it is, without a doubt, premature to say it will supersede the propeller … the tentative is interesting and we watch it closely.”

L’Aérophile observed: “If the machine would ever materialize as the inventor hoped, it would be a ‘beautiful dream.” And in all thoughtfulness, his dream became our reality. For now, we only have Henri’s words and few questionable articles released decades later as proof for its one alleged flight, on December 10 of the same year when “Coanda-1910” was revealed to the public.

According to Coandă and a number of articles, especially ones found in the Royal Air Force Flying Review magazine of the 1950’s and the 60’s, the plane actually flew but was struck by series of unfortunate events. The plane crashed and the flight went miserably with Coandă himself barely making it out alive.

Despite all controversies and wars for patent rights, Coandă was not really credited as the inventor of the first jet plane. However, the technology upon which the flying machine was built on sky rocketed all further research in the field and brought a brand new and much-needed perspective on how airplane engines should be built.

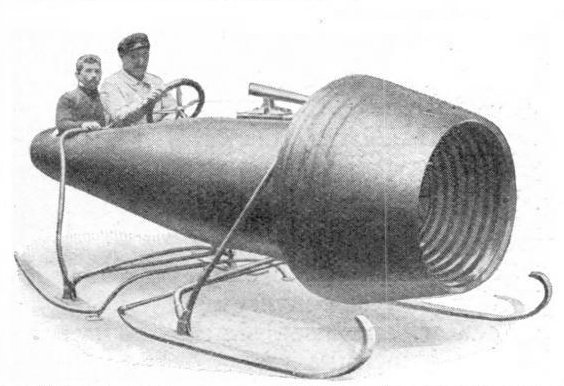

Coandă believed that a later invention could be the most important application of his earlier discovery. At a Symposionum organized by the Romanian Academy in 1967, he addressed the public famously stating: “These airplanes we have today are no more than a perfection of a toy made of paper children use to play with. My opinion is we should search for a completely different flying machine, based on other flying principles. I consider the aircraft of the future, that which will take off vertically, fly as usual and land vertically. This flying machine should have no parts in movement. The idea came from the huge power of the cyclons.” And today, we have the Harrier, and whole lot of other vertical takeoff jets.