“Three miles away from this spot you can find this pre-historic maze stone carved into a living rock face, proof that from ancient times man and his magic making with the world of spirit were active in this area.

The centuries have passed and times have changed and yet all around us in this quiet corner of England there is a strange feeling that we are not alone and that the shades of persons passed on and over into the world of spirit are very close. That is why this Museum of Witchcraft is located here. One is standing on the edge of the beyond.”

These are the words with which Cecil Williamson, the founder and the owner of one of the most peculiar shops in the world, once explained its existence and why precisely it exists where it does. It’s in Boscastle, Cornwall, near the dock and right beside the National Trust Visitor Center, where a vintage sign that says, The Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, swings gently on the sea breeze as a welcome for every visitor.

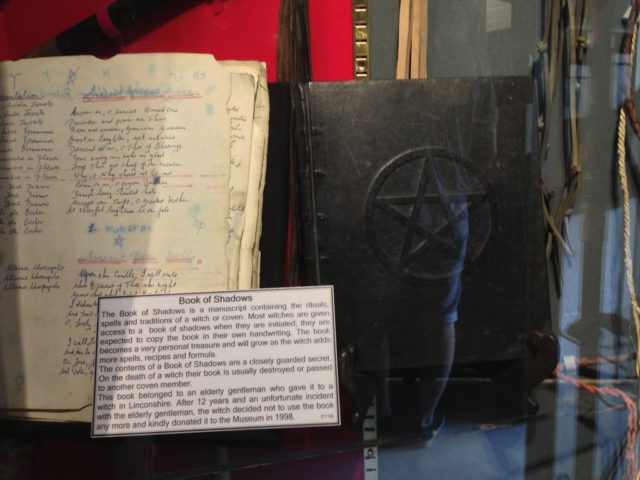

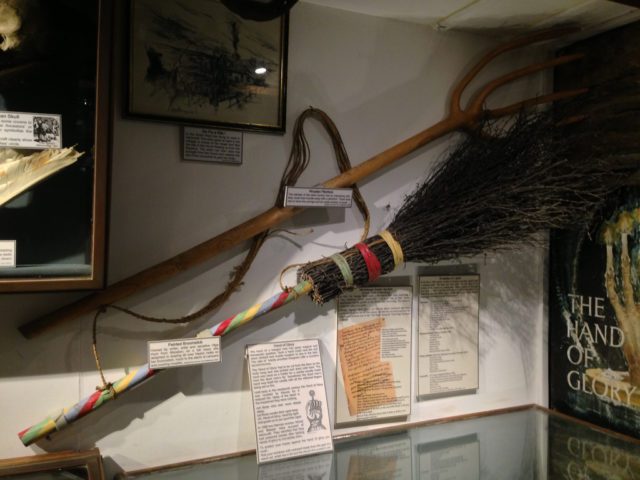

This pretty-looking little cottage by the sea currently holds the world’s largest collection of witchcraft-related artifacts, over 3,000 objects and 7,000 books that tell all about the long history of magic and the world of the occult. The collection ranges from statues of ancient goddesses, crystal balls, and artifacts worn by famous witches (their “flying” broomsticks and ouija boards that allegedly enabled people to have chat with the deceased) to all kind of different spells and lucky charms. One such includes a bumblebee-filled jar serving as a prosperity charm to those who at some point in history believed that holding it would bring them luck and make them prosper.

It’s an interesting set of samples gathered over the years by Cecil Williamson, who died in 1999. He was a man just as interesting as his unique collection. A film producer, he grew up in Paignton, a small seaside town in Devon, in southwest England, and very early on came to be captivated by the world of magic. It was when a schoolmate of his, a witch apparently, first taught him how to cast a spell that young Cecil was introduced to the world of magic. From then on, fascinated by witchcraft and spellbound by its power, Williamson began a search for anything that in his view was worth having. He wanted things out of the ordinary that in some way were related to the occult, just like some have a way of collecting rare vinyl records, old shoes, book’s first editions, coins, or comics.

As his collection was getting bigger and bigger, Williamson’s social circle was also growing, and in no time, it was packed with people of equal interests. Very soon he was sharing close friendships with influential people in the sphere he so adored, like Gerald Gardner, the founder of a fast-growing radical and highly sexual modern pagan religion known as Wicca, and the other one, probably the more famous one of the two, or infamous for that matter, Aleister Crowley. He was the occultist labeled “the Wickedest Man in the World” and whose name in the 1930s was a synonym for witchcraft and occultism. He was a self-proclaimed prophet of the Thelema movement he founded himself, and while our Cecil was not a prophet sent from beyond as Crowley and never founded a pagan movement, he did indeed found something that has lasted.

Williamson was a key part of a secret Witchcraft Research Center within England’s Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). He wasn’t agent 007, but still a man responsible to spy on and expose every bogus Nazi attempt at propaganda during the war. He was specifically charged with investigating the Nazis’ occult interests and pursuits. After the war ended, he found a way to use his skills as a filmmaker and what he learned from this and all his past adventures to bring the world of magic and witchcraft closer to people.

He opened a shop, a gallery of some sort, on the banks of the River Avon in Stratford-upon-Avon. It was a quiet little town near Birmingham, where a certain Shakespeare was born, and where this man believed he would prosper by orchestrating all kinds of different exhibits in the form of short documentaries that he himself made. But independently produced movies about the history of witchcraft, shape-shifting, and devil worship among many other things proved to be not of interest to the people living there. Cecil perhaps was not yet in possession of that prosperous bumblebee lucky jar.

Avon’s residents even tried to burn the place down with him in it, just like they burned witches in 17th century England. Fortunately, he survived unscathed along with most of his possessions, and in 1951 tried to reopen his shop on the Isle of Man, a self-governed city-state in the Irish Sea. This time he was not alone, but had the help of one of his dear occultist friends, Gerald Gardner, who had found large success with his new religion.

Their shop held a tall sign, The Folklore Center of Superstition and Witchcraft, and Gardner at the center of the attention served as a resident witch at the place. The Folklore Center was a lot different than the Museum of Witchcraft in Avon, more alive and focused on ancient ceremonial performance rather than on education and exploration, which is probably why their partnership didn’t last for long.

While Williamson intended to bring the world of magic closer to the “commoners,” and shed light on some misconceptions and common misinformation about the occult and the practice of witchcraft, Gardner tried to use their new enterprise as a place where he could perform his Wiccan rituals and market his religion, naked.

So after a whole decade of missteps, our interesting individual, in 1960, eventually made the right one by setting foot on the dock in Boscastle, which proved to be the place where his interesting idea could flourish peacefully and he could prosper by living it. Or maybe he found that jar in the meantime, who knows.

That jar, which we never failed to mention throughout the article for we believe it brings something special to the story and the rich history of the place and its founder, now after almost 60 years sits well preserved right next to a Hitler pin cushion. A voodoo doll made with the intention of stabbing it with pins and needles while singing a song first offered by the Readers Digest magazine during the war. You can almost hear the words:

Istan, come and help us, we are driving nails and needles. We are driving pins and needles into Adolf Hitler’s heart. We are driving nails and needles we are driving pins and needles… Cats will claw his heart in darkness, dogs will bite it in the night.

In 1996, struck by illness, Cecil was forced to sell his dream to a fellow pagan practitioner, Graham King, who did a fantastic job to keep the place alive, making sure his dream lived on. Moreover, under his guidance, the museum, now arranged thematically, rose to have international fame, recognized as the largest independent museum in the U.K.

Divided into two floors, each with a couple of rooms of their own, the place is now managed by the Museum of British Folklore. It grew to be somewhat of a preferable pilgrimage location for today’s witches and occultists, but still offers those educational lectures and shows for curious visitors just as its founder intended. For instance, this is the place where one can learn what a witch is, and that witches back in the day, as far as the 16th century, were actually never burned but hanged. For their spirit was believed to thrive in fire and shine even more when blazed.

On the other side, if one only wants to look around, there is the Wise Woman’s Cottage room to be explored or a room full of Aleister Crowley’s spells and charms for the prying eye, along with various rooms dedicated to modern witchcraft, Christian Magic, healing herbs, faeries, pixies, and most importantly, a room full of scrolls with all kinds of protection spells, where one can learn how to cast them.