Back in 1881, a massive earth-filled dam was completed by The South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club. This club catered to the super-rich and was frequented by numerous wealthy clients, including Henry Clay Frick and Andrew Carnegie.

This dam was built to hold back Lake Conemaugh, and the dam was named the South Fork dam.

By the year of 1889, the dam was in bad condition and in desperate need of repair.

Excerpt from The New York Times

A lake on the neighboring hills bursts its barriers and sweeps everything before it – men, women and children swallowed up by angry flood – awful scenes witnessed by survivors.

Pittsburg, May 31 – An appalling catastrophe is reported from Johnstown, Cambria County, the meager details of which indicate that that city of 25,000 inhabitants has been practically wiped out of existence and that hundreds if not thousands of lives have been lost.

A dam at the foot of a mountain lake eight miles long and three miles wide, about nine miles up the valley of the South Fork of the Conemaugh River, broke at 4 o’clock this afternoon, just as it was struck by a waterspout, and the whole tremendous volume of water swept in a resistless avalanche down the mountain side, making its own channel until it reached the South Fork of the Conemaugh, swelling it to the proportions of Niagara’s rapids.

The flood swept onward to the Conemaugh like a tidal wave, over twenty feet in height, to Johnstown, six or eight miles below, gathering force as it tore along through the wider channel, and quickly swept everything before it.

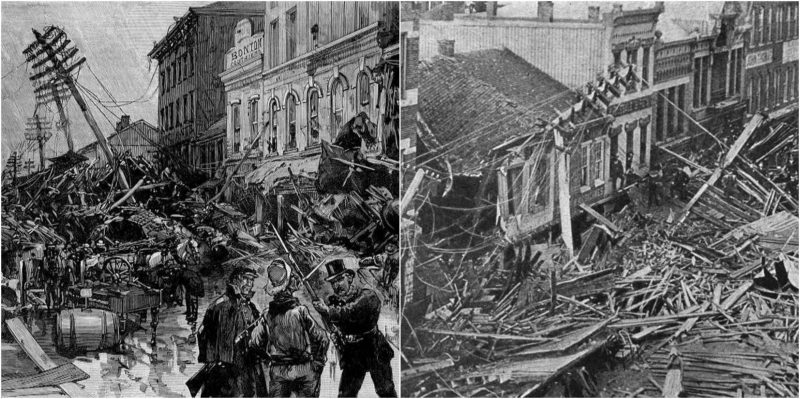

Houses, factories and bridges were overwhelmed in the twinkling of an eye and with their human occupants were carried in a vast chaos down the raging torrent.

History of the Dam

Between 1838 and 1853 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania constructed the South Fork Dam, as part of a canal system that was cross-state.

The Eastern terminus of the WDC (Western division canal) was in Johnston and it was supplied with water from the nearby lake Conemaugh. As rail transport was the preferred method over canal transport in these times, the canal was abandoned and sold to the Pennsylvania Railroad, included within this purchase were the lake and the dam. The railroad went on to sell these off privately.

As rail transport was the preferred method over canal transport in these times, the canal was abandoned and sold to the Pennsylvania Railroad, included within this purchase were the lake and the dam. The railroad went on to sell these off privately.

A group of private spectators, led by Henry Clay Frick, bought the reservoir, modified it and converted it into a private resort that was to be used for their wealthy associates. A lot of these people were connected through business links and social links to the company Carnegie Steel.

The development of the reservoir included the lowering of the dam so that a road could be supported above it, and adding a fish screen into the spillway, with the added benefit of this screen trapping any debris. The alterations made to the dam are thought to have made it more vulnerable. There was originally a system of valves and relief pipes within the dam but these had been sold for scrap and were not replaced as part of the renovation. This meant the level of water could not be lowered, in the event of an emergency.

Cottages and an exclusive clubhouse were built which made up the creation of the South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club and their membership was taken up by more than fifty very wealthy steel, railroad and coal industrialists of Pittsburgh.

A lot of these people were connected through business links and social links to the company Carnegie Steel. The development of the reservoir included the lowering of the dam so that a road could be supported above it, and adding a fish screen into the spillway, with the added benefit of this screen trapping any debris. The alterations made to the dam are thought to have made it more vulnerable.

There was originally a system of valves and relief pipes within the dam but these had been sold for scrap and were not replaced as part of the renovation. This meant the level of water could not be lowered, in the event of an emergency. Cottages and an exclusive clubhouse were built which made up the creation of the South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club and their membership was taken up by more than fifty very wealthy steel, railroad and coal industrialists of Pittsburgh.

The Lake (Conemaugh) was 450 feet in elevation, at the site of the club; it was approximately 2 miles long, had a width of 1 mile and reached depths of 60 feet besides the dam itself. The perimeter of the lake was 7 miles and was composed of 20 million tons of water.

The dam itself was 72 feet tall, with a length of 931 feet. Following the opening of the club, the dam frequently leaked and was patched often (usually with straw and mud). Concerns of the dam’s effectiveness had been voiced by the Cambria Iron Work’s head, based further downstream.

In 1889, May 28th, a storm formed above Kansas and Nebraska and started to head eastwards. Two days later this storm hit Johnstown and was the worst ever downpour the town had recorded. The United States Army Signal Corps guessed at there being 6-10 inches of rainfall within 24 hours. The river running through the town was very close to bursting its banks.

The President of the club, Elias Unger, woke up to a swollen lake Conemaugh following the overnight downpour; he ran out to try and assess the situation in the pouring rain and noticed the water was almost breaking over the dam. He gathered a group of men to try and unclog the spillway, to attempt to save the dams face, other men tried to relieve some pressure at the other side of the dam but this failed. A lot of men stayed on the dam, using earth to try and raise it and piling rock and mud onto its surface to strengthen the walls.

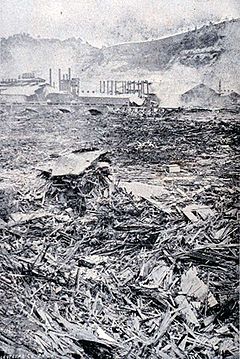

At approximately 3.10pm the dam collapsed, letting loose the 20 million tons of water held behind it. The waters of Lake Conemaugh ran down into the Little Conemaugh River. Just 40 minutes later the Lake was empty; all the water had escaped through the broken dam. South Fork was the first town to be hit by this water; most people managed to run up hills nearby but 20-30 houses were washed away or destroyed and a total of 4 people were killed.

As the water headed towards Johnstown the floodwater started picking up debris (animals, houses and trees) and as it hit the Conemaugh Viaduct the water was temporarily stopped as this debris jammed against the arches of the structure. This blockage lasted 7 minutes; then the viaduct gave way and the flood continued onwards. Because of the stop/start motion the water had renewed vigor and was stronger than before. Mineral Point, a town 1 mile under the viaduct, was hit next by this water and it wiped out the entire street that made up this village and all 30 families that resided there.

East Conemaugh was the next town in the waters path, an engineer in a nearby locomotive witnessed the waters coming towards the town and blew his whistle loudly and constantly; this alarmed some people who managed to get to safety. The waters rolled in, picked up the locomotive and threw it aside, the engineer survived but at least of 50 others died, 25 were passengers that were on trains in the town.

As the waters approached Johnstown they hit the Cambria Iron Works in the town of Woodvale; picking up barbed wire and railroad cars on its way. A total of 314 of the 1100 Woodvale residents died when this happened.

The flood hit Johnstown 57 minutes after its original breach of the dam. The waters were 60 feet tall in places and rushed forwards at 40 mph. People tried to flee to high ground but most were caught in the fast water, a lot were crushed by debris.

Those who reached attics in their homes or managed to cling onto floating pieces of debris waited hours for any help to come. The Stone Bridge was a feature in Johnstown and carried the Pennsylvania Railroad across the River Conemaugh.

The flood rushed towards the bridge and the debris stuck against it; creating a dam and forcing the flood to go upstream. This lasted until gravity kicked in and caused a second, fresh wave to hit Johnstown; this time coming from a different direction.

People who had found themselves washed downstream now faced an inferno as the debris caught fire; some 80 people died in this. The fire at the bridge burned for a total of 3 days; once the waters had gone the debris was seen to cover a total of 30 acres and reached a height of 70 feet.

This debris took three months to clear; with the help of dynamite. The Stone Bridge still stands today and serves as a monument of this terrible flood.

It was restored in 2008 and had new lighting added and it is used in commemorative activities. The total number of deaths in this flood reached 2209; this was the largest loss of life (civilians) in the US at this time. Entire families were killed (99 in total) and 396 children. 124 women and 198 men were made widows/widowers and 98 children became orphaned.

A third of the dead were never identified and so were buried in Grandview Cemetery in a section known as ‘Plot of the Unknown).This was the worst ever flood that happened in the United States in the 19th Century. A total of 1600 houses were destroyed, as well as 4 square miles of Johnstown.

Property damage totaled $17 million.

The operation to clean-up continued for many years; although the nearby Cambria Iron & Steel managed to return to production within 18 months.