A large portion of today’s San Francisco is built atop piles and piles of vessels that in the mid-19th century shipped hundreds of thousands of gold-crazed prospectors from all over the world to San Francisco Bay in California–but they never made the trip back.p

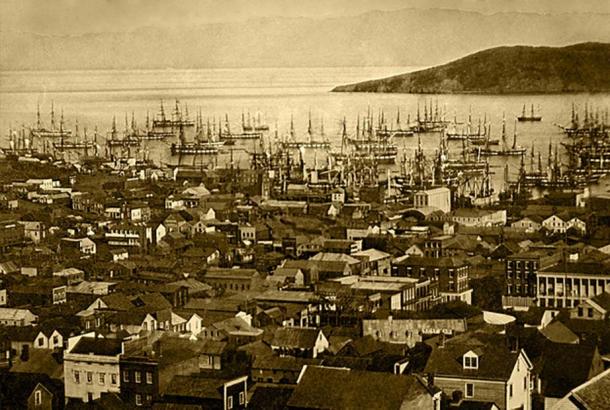

According to San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, there are dozens of scuttled ships that are buried underneath the city streets and those massive sleek skyscrapers in the Embracadero and the Financial District, two of the lowest parts of the city. It is an area that was previously a shallow stretch of water called Yerba Buena Cove, at one point referred to as the “forest of masts” by 19th-century chroniclers who had witnessed the most interesting of sights. Thousands of ships were all cramped up and tangled in little to no space like herrings in a cask. And one of those ships is today the Old Ship Saloon on 298 Pacific Ave, San Francisco. It was the grand Arkansas back in its prime, and it is just one of the hundreds that are now either marked with a sign or lay hidden from sight beneath the city’s infrastructure.

Which begs the questions of how and why. How did it come to this? Why were so many ships abandoned and left to rot underground?

As the Maritime National Historical Park has readied a new map and marked every location where archaeologists believe they found signs of shipwreck, the answers point directly to Sutter’s Mill and James Wilson Marshall, who saw gold glitter in the American River in Coloma and sparked the Gold Rush in California. Whatever followed after was, shall we say, history.

But let us draw a straight line through time and try to explain.

After James, to his amazement, discovered loose flakes of gold floating in the river near Sutter’s Mill in South Fork that glorious morning of January 24, 1848, word got out that huge piles of gold were found and even more were waiting to be discovered. News spread quicker than a summer fire through a thick forest, and by spreading we mean, a man was running and screaming in madness through San Francisco with a vial full of gold in his hand: Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!” He was, of course, Samuel Brannan and his insane yelling down the city streets set off one of the greatest migrations recorded in American history.

California’s Gold Rush was set in motion, and every pick, shovel, and gold pan equipped man that arrived in San Francisco with nothing but a future full of gold sparkling on his avaricious mind and a loaded rifle in his greedy hands had no intention of ever going back until those prospects promised were fully realized. They had a song stuck in their head probably, as they were headed toward the Sierra Nevada mountains and the plains down in Central Valley, on the hunt for large gold deposits and to dig, dig, dig them until they’d dug, dug, dug, every gold nugget out and emptied the Sacramento River from every loose flake drifting downstream.

According to all reports, between 1849 and 1857 men were literally running in haste to be the first to get their hands on the gold that was now free for the taking. After all, they had to–they had nothing left.

Everything they once were was thrown away for an idea of what they could become. Overshadowed by dreams of lives lived in richness and wealthy delights, everything they owned was sold or mortgaged, what could have been borrowed was borrowed, their businesses closed until further notice, their wives left behind to juggle between playing a mom, a dad, and every other role they needed to play on their own.

From a small city of about 1,000 in 1847, San Francisco by the end of 1849 counted no less than 100,000, including the small settlements of the surrounding area. And its shores housed thousands of ships on which these newcomers arrived. Most of them old and worn out, sent on their last voyage, and others with captains and sailors who saw gold digging to be more prosperous than to sail them back from where they came, the ships remained docked until they rotted in place.

But actually, they were never really abandoned, according to Richard Everett, curator of the Maritime National Historic Park, and maritime archaeologist James Delgado. Well, a few of them were, but as it was stated by them during a podcast interview for KQED TV, most were either deliberately sunk in the shallow waters of Yerba Buena Cove or dismantled plank by plank and put to a good use as something else entirely.

The law back then allowed for salvage rights over the land where a ship had sunk and, according to Everett, many did just that to theirs or other people’s ships to claim precious lands and convert the shipwreck into something else. Such was the fate of the Niantic for instance, who was run aground in what is now the corner of Clay and Sansome streets of the Financial District and converted into a permanent land structure. It was used as a hotel, warehouse and whatever else that folks of a city that all of a sudden grew to be the bustling center of the new frontier needed. Similarly, a ship named Arkansas was transformed into a bar with a gangplank leading the way from the sandy seashore up to a drink of choice, and Euphemia into a prison in times when prison cells were in deficit.

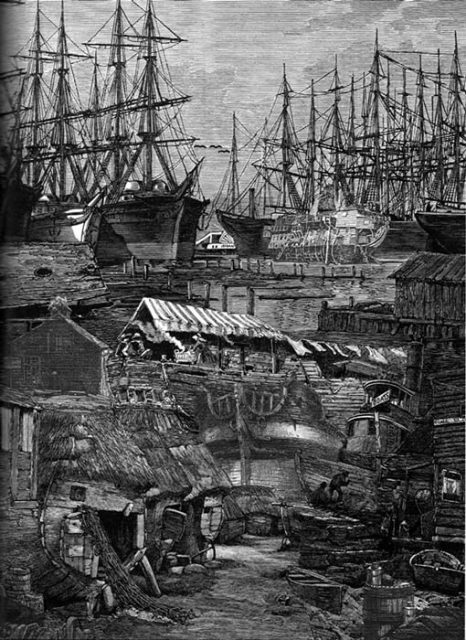

During the height of the gold excitement, there were at least five hundred ships stranded in the harbor, some without even a watchman on board, and none with a crew sufficiently large to work her. Many of these vessels never sailed again. Some rotted away and sank at their moorings. (Herbert Asbury in “The Barbary Coast”)

San Francisco needed more structures and many of the smaller ships that were already decaying at Rincon Point, the most condensed part of the cove, were systematically taken, piece by piece, and recycled into building materials. Not that they were abandoned and all that, but it was a good pay for something that was of no use at all.

While the majority were after the gold up in the mountains and down the rivers, some saw another opportunity for profits to grab there and then on the spot. Rather than digging it in the mines and chasing it down the streams hoping for a lucky strike, they saw gold from banking, hotels, shops, storage houses, restaurants, and brothels, for instance, where luck was not needed at all. Only men, and they were more than enough.

Charles Hare, as an example, saw a ship junkyard in his visions to help everything come alive, and out in front of it a big sign that said “Rotten Row.” He and his 100 employees ran a fruitful salvage business and their recycling apparently laid the groundwork for big city San Francisco, according to Everett.

Bucket by bucket the shallow stretch of water was gradually filled with sand by folks who wished to landfill the sides and secure their scuttled ships-turned-structures or those who needed new lands to build something out of the wreckage on top. And as the shoreline was being pushed away, the city was growing bigger and bigger. That part exactly today is the Financial District and the Embracadero, the lowest parts of San Francisco.

Unfortunately, wood can’t stand a chance against a ravaging fire and almost all wood-made or ship-made was burnt down to the ground by the great fire of May 4, 1851. The scorched leftovers were covered with sand and earth after the fire and the city was built from the ground up, but parts of these ships now long lost and forgotten were left underground when the marshland was turned into fresh land for construction.

They do pop out from time to time to remind us of a time of great rush and golden dreams. For instance, during a conversation with the owner of a bar named the Old Ship Saloon, if he is willing to slip a thing or two of why the ship is named as it is, or when a tunnel digging procedure will lead you directly to a ship so huge that you simply know something fishy is going on beneath the ground surface.

The vessel’s name was Rome and it was discovered in 1994 just south of Market Street and right beneath Justin Herman Plaza on the Embarcadero, almost two decades after hull remains of the Niantic were excavated underneath the Mark Twain Plaza Complex of the Financial District in 1978.

Two greats among so many found and located, and even more that are just waiting for people to uncover their remains and speak of their rich histories, or in particular about those few years when they were a part of the grand “forest of the masts” in San Francisco.