Robert de La Salle was a French explorer who had a fleet of four ships when he explored the Gulf of Mexico with the intention of starting a French colony at the mouth of the Mississippi River in 1685. The La Belle was the flagship in his fleet on that voyage.

In 1686, the La Belle was wrecked in what we know today as Matagorda Bay, meaning his quest for the colony start-up did not happen.

In 1995, a team of archaeologists found the La Belle that had been sitting at the bottom of the Gulf for over 300 hundred years, totally forgotten.

This discovery is one of the most highly regarded finds for archaeologists and major recovery expedition that took over a year. When the ship was recovered, there were over one million artifacts aboard.

In the 1970s, Kathleen Gilmore, of Southern Methodist University, studied historical accounts of the La Salle shipwrecks, and gave her thoughts as to where the La Belle could be found. The Texas Historical Commission, in 1977, asked an independent researcher to look through the archives in Paris for any information on the La Salle shipwrecks.

The researcher found original copies of maps made by Jean-Baptiste Minet, La Salle’s engineer. Minet made detailed maps of Matagorda Bay and the pass and the spot where the LaBelle went down before he returned to France on the Joly.

Other maps were found, including some that showed where the La Belle sat in the Gulf. Barto Arnold, State Marine Archaeologist for the Texas Antiquities Committee (previous name of the Texas Historical Commission), suggested a 10-week search for La Salle’s ships in 1978. During the hunt for La Belle, other shipwrecks were found in the general area for the La Belle. For the next 17 years, due to a lack of funding, any more attempts to locate the La Belle were unable to proceed.

The Texas Historical Commission, in June 1995, put together a second magnetometer search of all the most likely areas not in the original surveys. Since the original survey, GPS positioning has become available to help navigation and make the relocation of targets much easier and more accurate.

The second survey took an entire month and used a Geometrics 866 proton magnetometer, which identified 39 “magnetic features that required further investigation.” The 39 features were listed in order of importance, and on July 5th 1995, divers were sent to the most probable location.

In the first diving exercises, a prop-wash blower (a metal pipe fitted over the propeller to deflect its force down to the seafloor) was used, to make the visibility better by forcing surface water down towards the bottom. The archaeologists decided it was better to turn the blower off because it was damaging the material of the remains of the cargo.

Nobody knows the amount of sediment that was covering the shipwreck when it was found because the prop-blower had been sent down before the divers got there. The first divers stated that they thought they felt musket balls on the seafloor along with loose fragments of wood moving with the current that was made by the blower.

Because of these finds, it was strongly suggested that this was the site of the La Belle. Archaeologist Chuck Meide found a bronze cannon which, when recovered, proved that this was the shipwreck of La Belle.

When the cannon was recovered, they discovered that it was ornately decorated, and showed the illegitimate son of Louis XIV, Vermandois, who served as admiral of the French fleet until he died in 1683, meaning the cannon could not have been cast any later than 1683.

All of this was considered very strong circumstantial evidence that this was the La Belle. There was a serial number on the cannon (and two others found in 1997) that matched French archival records that were found by Dr. John de Bry with the numbers of the four bronze cannons that were on the La Belle.

Those records provided definite proof of the ships identity. Local watermen may have known about the ships location prior to the discovery in 1995. The excavations in 1996 by the archaeologists of the Texas Historical Commission, found evidence that one of the four bronze cannons that had been loaded onto the La Belle, had been removed sometime prior to the excavation, maybe decades earlier.

For some reason, they assumed it was removed by a local shrimper who could have accidentally caught the cannon in his net.

Nobody knows the whereabouts of the missing cannon, and there are no other signs of prior artifact removal at the site. The team of archaeologists spent a month diving and documenting the wreckage and its extent and condition. They recovered several artifacts. Due to the historical significance of the wreck, the dark waters of the Bay which directly limited the visibility of the divers, they made the decision to build a cofferdam around the site.

A cofferdam is a double-walled steel structure, that has compacted sand between the two walls, and it surrounds the entire wreck. The structure cost 1.5 million dollars and was paid for by the state of Texas, though funding and federal grants would pay for the excavation.

When it was finished in September 1996, they had to pump out the water in the cofferdam and the ship was finally exposed to air for the first time in over 300 years.

A larger team of around 20 archaeologists, assembled in the town of Palacios and were given the task of completing the excavation of the shipwreck under the supervision of Dr. Jim Bruseth.

This task lasted from July 1996 to May 1997 and was deemed one of the most significant maritime archaeological excavations of its time.

When the muddy sediments were removed from the wreckage, there were several wooden boxes and casks that held a wide variety of artifacts.

The La Belle had held all the salvaged supplies from the wreck of the store ship L’Amiable, and of course, this gave the archaeologists a unique insight into the supplies that were felt necessary for the start of a successful colonization venture.

Texas had been claimed by the Spanish, who were considered the rivals of the French at the time. The Native Americans were hostile, and there was a wide array of weapons on board the ship including three bronze cannons, one iron swivel gun, many casks of lead shot and gunpowder, several boxes of muskets, a handful of ceramic firepots that were used like hand grenades, and several sword handles.

There were also tons of trade goods such as black, blue and white glass beads, brass pins, brass hawk bells, wooden combs, brass finger rings with Catholic religious symbols, and a barrel of iron axe heads.

Tools and supplies such as smelting crucibles, shovel, rope, a cooper’s plane, and long bars of iron stock were also recovered, as were a variety of the ship’s hardware and rigging components.

There were also remains of a salt pork, skeletal remains of rats, and the trophy skulls of deer complete with antlers. There was one complete human skeleton discovered, it was that of a middle-aged man with signs of arthritis.

Part of the man’s brain was still intact, preserved by the anaerobic environment caused by the thick muddy sediments of the bay.

After the osteological analysis, the human remains were interred at the Texas State Cemetery. By the start of March 1997, all the artifacts had been removed from the hull. After that, the archaeologists concentrated on the remains of the ship.

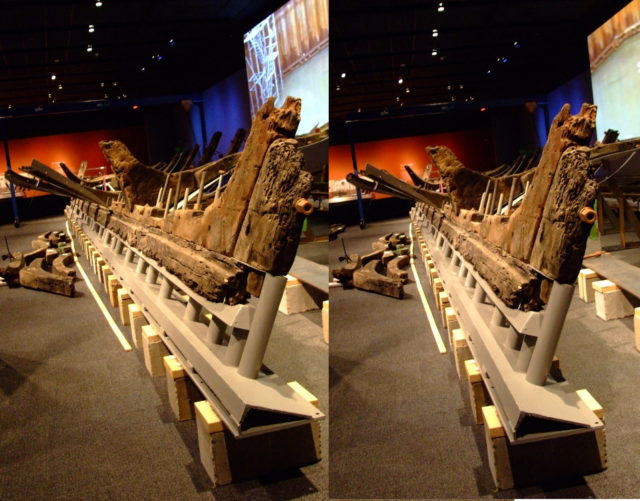

They disassembled the entire ship, each timber being carefully recorded before and after it was removed from the hull. It took them three months to complete that task, after which the cofferdam was broken down and sold.

The timbers that were recovered were reassembled in a special cradle and vat that was designed at Texas A&M University’s Nautical Archaeology Program. This is the establishment in charge of the conservation of all artifacts that were recovered from the wreck site after 1995.

The process to preserve the hull took over ten years by soaking it in polyethylene glycol and then freeze-drying it. More than 300 years after the shipwreck, the French government filed an official claim to the ship and its contents, after the excavation was completed.

An official naval vessel is owned by the country under which the ship flies its flag, under international naval laws. Even though there is a long-standing tradition that is repeated by American historians that LaBelle was a personal gift from the King to La Salle, there were no documents that showed proof confirming the French claim.

Archival research that was conducted in French depositories showed two official documents that listed LaBelle as being loaned to La Salle by the King who owned it. United States Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, conceded claim in favor of France just before the end of the Clinton administration.

On March 31st 2003, after a several-year negotiation, an agreement was signed which gave official titles to the wreck and its artifacts to the Musee National de la Marine in Paris. The day-to-day control over all of it was given to the Texas Historical Commission for 99 years.