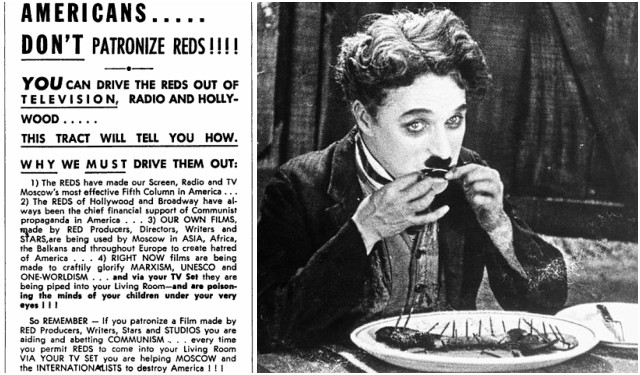

During the prime phase of the Cold War, from the late 1940s through the 1950s, there was no greater crime in the United States than to be a suspected communist.

The fear of communism, known as the Red Scare, led to a national witch hunt for suspected communist supporters.

The witch hunt began at a federal level, thus the federal employees were analyzed and further determined as sufficiently or insufficiently loyal to the government.

The witch hunt eventually trickled to the ground level, so many artists, musicians, writers and movie stars within the United States were labeled as suspected communists.

These accusations were mainly focused on Hollywood where hundreds of actors, actresses, directors, screenwriters and other entertainment professionals were barred from working.

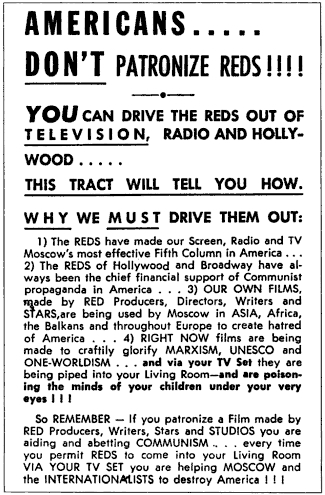

The Hollywood blacklist contained the name of Charlie Chaplin who was accused of being a communist by senator McCarthy. Presumably, there was a produced file which detailed his subversive political activities since 1922.

Chaplin was living in America for nearly 40 years when he was put on an FBI blacklist in 1948.

He was one of the 300 people blacklisted by the Hollywood film studios and prevented from working in Hollywood. When he was asked if he was a member of the Communist Party, Chaplin said: “I do not want to create any revolution, all I want to do is create more films”.

In the autumn of 1952, Chaplin and his family were sailing on Queen Elizabeth to attend the London opening of his film “Limelight”, when he was informed that he would be arrested if ever returned to America.

Attorney General James McGranery had rescinded his re-entry permit on suspicion of the Communist inclinations and announced that Charlie Chaplin would have to answer questions about his political views and moral behavior before being allowed to re-enter the country.

McGranery ordered the Immigration and Naturalization Service to hold Chaplin for hearings in case he attempted to return.

On 23rd September Chaplin arrived in Southampton and in the evening gave a press conference in London, impugning to be a Communist, but rather someone “who wants nothing more for humanity than a roof over every man’s head”.

Chaplin chose to remain in Europe and said that he wouldn’t go back to the USA even if Jesus Christ was the president. He settled in Switzerland and remained there until his death.

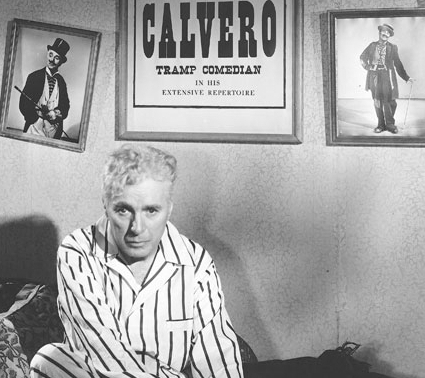

Chaplin shot two more features in London, “A King in New York” in 1957 and “A Countess from Hong Kong” in 1967. Both films had leading roles of refugee characters.

We have another story on Chaplin: This is Charlie Chaplin’s first movie and apparently, he hated it

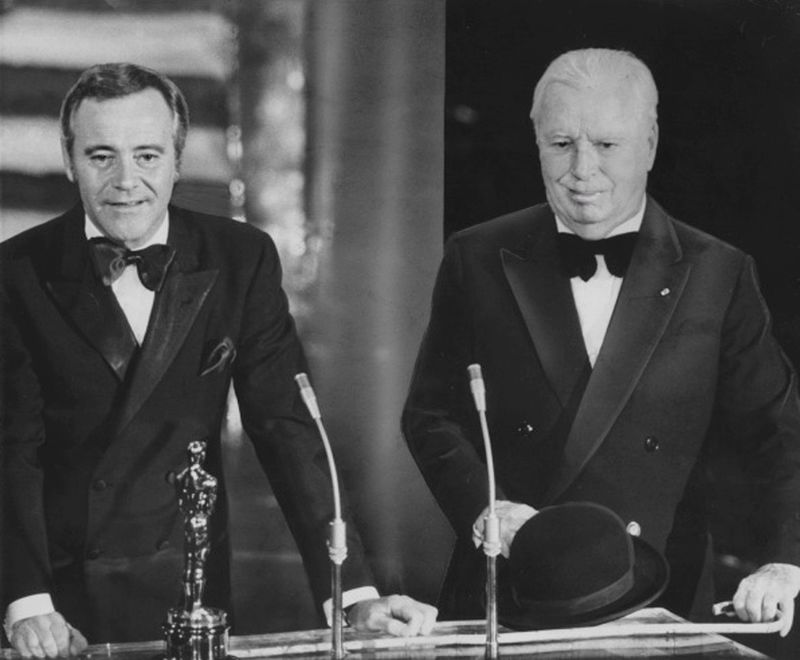

However, Chaplin returned to the United States in 1972 and accepted a special Oscar at the Academy Awards ceremony, receiving a standing ovation.