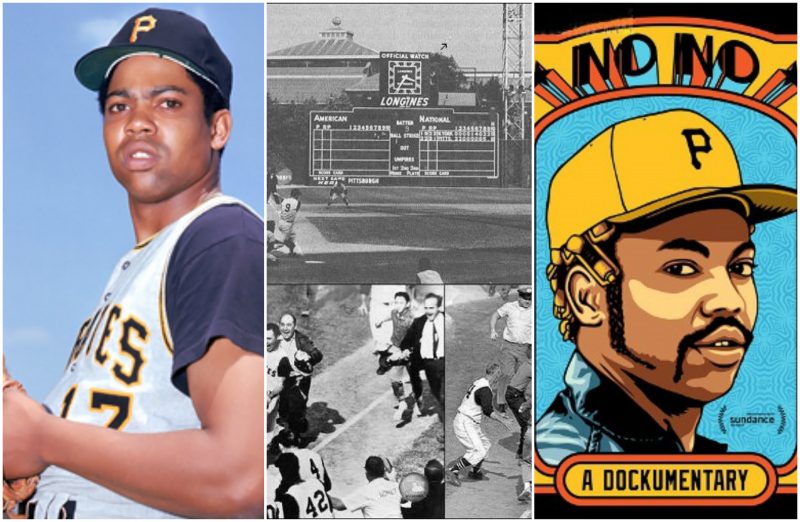

Dock Phillip Ellis, Jr. (March 11th, 1945 – December 19th, 2008) was an American baseball player known for his volatile attitude on and off the pitch.

Opposing strict baseball norms by wearing hair curlers during a match, the fabled player was a true baseball dissident.

He was a World Series Champion in 1971 while playing for the Pirates, appeared at the Major League All-Star Game, helped lead the Yankees to the 1976 World Series and was a “Comeback Player” in the same year. An outspoken advocate for the rights of players and African Americans, he opposed the slightest hint of racism in sports with violent outbursts.

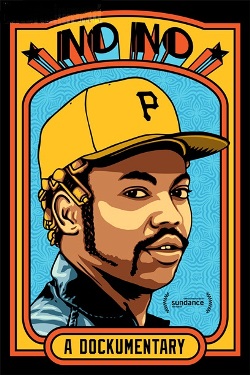

His lifetime achievements are almost overshadowed by his famous no-hitter pitch on June 12th, 1970, while on the effects of LSD.

Ellis was a constant thrash-talker and a loudmouth, as his records show numerous acts of aggression on and off the field.

The rowdy behavior was triggered by alcohol or drug-fueled brawls, but he compensated through his competitiveness and outstanding baseball skills.

He was arrested for grand theft auto, chased a heckler with a baseball bat, got maced by a security guard for refusing to show his ID, bean balled a couple of players, constantly got into fights, etc. There had never been a dull moment in his career.

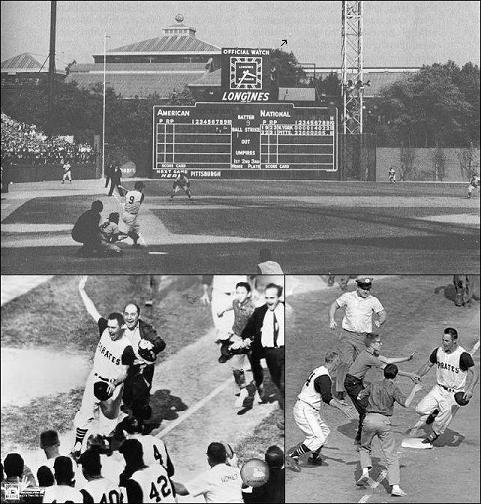

As a right-handed pitcher, Ellis played in the Major League Baseball (1968 – 1979) for various baseball teams: the Pittsburgh Pirates, New York Yankees, Texas Rangers, and other teams. With an impressive 138–119 win–loss record, a 3.46 earned run average and 1,136 strikeouts, Dock Ellis certainly makes up for his exuberant demeanor.

He studied at Gardena High School in California and had a very intense childhood. He played basketball for the school team but refused to participate in baseball because of racial remarks and insults.

When he got caught smoking marijuana and drinking on campus, the school administration, knowing that he would show as an excellent player, promised not to expel him only if he agreed to play in the team.

Chet Brewer, a right-hand pitcher. He played alongside Ellis in the “Pittsburgh Pirates Rookies”. Photo Credit

Ellis was diagnosed with an inherited blood disorder, which caused him problems throughout his career. Supposedly, this extended his erratic behavior and drug abuse. He explained that he used drugs not only to numb the pain but to avoid the fear of failure.

He retired in 1980 because he “got bored playing baseball”. In contrast to his drug-fueled antics, he worked as a drug counselor and also trained minor league players.

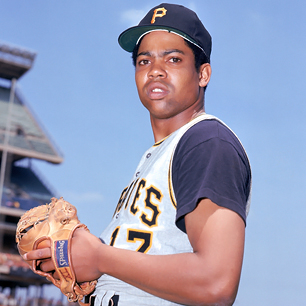

The pitch

The Pittsburgh Pirates took a flight to San Diego on June 11th. They were scheduled to play against the San Diego Padres. Meanwhile, Ellis was visiting a girlfriend in Los Angeles and as he thought that he had the day off, he took an LSD at noon.

He completely forgot the fact that he was slated to start the game against the San Diego Padres. He wasn’t even aware that he had to play that day, reportedly losing any sense of time (perhaps even space).

Fortunately, his girlfriend had accidentally found out in a newspaper about the game scheduled for that day.

Dazed and still affected by the LSD, he rushed to the airport, took the flight from LA at 3 PM and arrived at the San Diego Stadium at 4:30 PM. The game started at 6:05 PM.

The baseball legend had been “high as a Georgia pine” at that point. He threw the startling no-hitter on a faithful Friday, June 12th, 1970, without feeling the ball on his fingers or even see straight. Jerry May, the Pirates’ catcher, wore a reflective tape on his fingers so that Ellis could see the signals.

Ellis managed to walk eight batters and struck out six while being aided by the second baseman, Bill Mazeroski’s and the center field, Matty Alou. Ellis never used LSD that season again.

He claimed that the scariest moment of his career was when he soberly attempted to pitch in a 1973 game.

Dock Ellis recalled the moment:

“I only remember bits and pieces of the game. I was psyched and had a feeling of euphoria. I was zeroed on the catcher’s glove, but didn’t hit it too much. I remember hitting a couple of batters and that the bases were loaded two or three times.

The ball was sometimes small and at times it was big. Sometimes I could see the catcher, sometimes I couldn’t. I tried to stare the hitter down and throw while I was looking at him. I chewed my gum until it turned to powder.

I had a crazy idea in the fourth inning that Richard Nixon was the home plate umpire, and once I thought I was pitching a baseball to Jimi Hendrix, who was holding a guitar and swinging it over the plate. They say I had about three to four fielding chances. I remember diving out the way of a ball which I thought was a line drive. I jumped but the ball hadn’t been hit hard so it didn’t reach me”.

Dock Ellis died of a liver ailment in 2008, at the age of 63.

It took him 10 years to admit that he was intoxicated during that historical moment. It was obvious that Dock Ellis’ nonchalant vigor was doing all the work for him. He did it for the laughs.

The rumors that he had actually underwent the influence of the psychedelic drug were doubtful and widely dismissed by reporters when Ellis admitted it during an interview in 1984. Bill Christine, a reporter, claimed that he didn’t see anything unusual, as he spent the whole day with the team.

With his dull senses and his hand/eye coordination way out of sync, Dock Ellis managed to pitch a 2-0, eight-walk no-hit victory. In Major League Baseball history there have been 295 no-hitters, but there has never been anything like Ellis’ “cosmic” pitch.

Baseball is one of the most difficult sports to play, especially when it comes to major league games where skilled sportsmen condone drug-free lifestyles and strict routines.

What Ellis managed to pull off is a mythical feat followed by outstanding plays, as even his team hadn’t noticed that he was completely high off his mind.

This unusual event along with the idea of everyone getting high all the time because of crooked drug controls started to build itself up on a larger scale, thus provided one of the best moments not only in baseball but in sports history in general.

During the psychedelic era of mellow policies, bendable rules and Jimi Hendrix tunes, drug use was not unusual. Today, athletes are under a strict surveillance. Drug tests are done on a regular basis, so the odds of a legendary feat like this are highly improbable to happen again.

Dock Ellis will be remembered not only for his blitzed beyond belief pitch but also for his unbreakable will for justice, fight against racism and most importantly, making baseball fun.