Ah, birthdays! The unwrapping of presents accompanied by the chatter of friends and family and party music in the background, a celebration of another year of your life. And here comes the cake and a sing-a-long of “Happy Birthday to You.” A momentous touch of the celebration: the cake’s topping covered with lit candles that you can’t wait to blow out with a hopeful wish, cheered by those around you.

Birthday celebrations have been practiced for decades. However, the origin and evolution of their main features (the cake, the candles, the song, the wish) are intriguing.

Some historical records say that the Ancient Romans were the first to celebrate birthdays with a specially made sweet pastry that resembled bread (cake and bread were rather interchangeable terms in the past). The content of the Roman cake would be a winner recipe for any modern hipster-patronizing restaurant today: flatbread made from nuts, yeast-leavened and no sugars added–only honey (hopefully, organic).

The Romans had three different types of birthday celebration: a personal, private one with family and friends; the birthdays of past and present imperial emperors who were honored with celebration; and finally, a person’s 50th birthday, which was particularly special and was celebrated with honey cake made of wheat flour, olive oil, honey, and cheese.

Other historians think that the Ancient Greeks, with their honey cakes and bread, were the ones who initiated the custom of having a birthday cake.

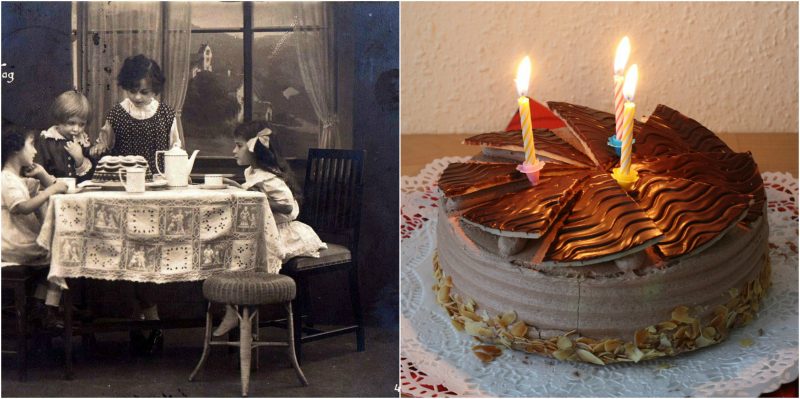

Yet another theory regarding the tradition of a celebratory bread or cake suggests that it originated in Germany in the Middle Ages as a sweetened baked dough previously shaped as baby Jesus, as a commemoration of his birthday. This cake was upgraded in the early 15th century when it began to resemble what we enjoy today. The Germans celebrated young children’s birthdays with cake, naming the celebration Kinderfest–the nearest prerequisite of contemporary children’s birthday parties. These cakes were similar to the Romans’ festive bread but progressed into what was called Geburstagtorten–a sweeter, richer cake version.

The design of the cakes, as well as the content, became more pleasing in the 17th century, when sugary icing, decorations, and layers were introduced. These new cake elements required high-quality ingredients and production, which were quite expensive and only affordable by the upper classes. This changed with the onset of the industrial age, when baking utensils and food became more accessible. Desserts and cakes saw a considerable price drop while the production increased. Due to mass production, bakeries started offering ready-made cakes at lower prices.

It wouldn’t be complete to talk about the tradition of the birthday cake without mentioning the origin of the lit candles, which, like a sparkling crown, adorn the top of each cake. According to some, the Ancient Greeks not only came up with the birthday cake but also the lit candles. The goddess of the hunt, named Artemis, was regaled with cakes that people brought, each adorned with lit candles that were supposed to imitate the moon or moonlight, Artemis’ popular symbol. It was believed that the smoke from the candles carried people’s prayers to their gods. Supposedly, this ancient belief explains why today people make a wish before they blow out their birthday candles.

Another theory suggests that the Germans were the initiators of the birthday candles’ tradition. A record from the mid-18th century about Count Ludwig Von Zinzendorf’s extravagant birthday party talks about an oven-size cake containing a number of holes with a candle in each, the amount totaling that of the years being celebrated. These customs are present even today, as a silent wish must be made prior to blowing out all the candles that total the person’s age.

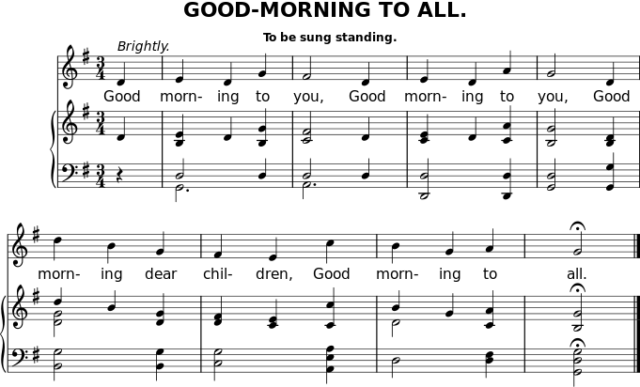

Finally, what would any birthday candle-blowing be like if not accompanied by the “Happy Birthday” song? It may surprise you that the first title was “Good Morning to You,” written in 1893 by two teachers, Patty Hill and Mildred J. Hill, as a student-welcoming song before classes.

The song became popular in America, so in 1924, Robert H. Coleman presented it in a songbook with an alternate stanza. This version became highly popular and quickly overshadowed the original lyrics after it appeared in some films and Broadway musicals. It was even used for Western Union’s first singing telegram.