The Vikings are well known for documenting their culture as well as their travels, wars, and triumphs. Asgard and Valhalla have become a household name for both historians and students in modern society.

And while there are tons of documented accounts of the Vikings, very few accounts are as thorough as the Viking’s discovery and first settlements of Iceland.

It’s known by historians that Icelanders from the Medieval era were focused on their ancestry for a couple of reasons. While it’s common for societies to search for a bigger meaning of their histories and beginnings, the Icelandic population had something more important in mind. There was a war occurring in the country over the rights of property, and the country believed that diving into their past would settle the score over the land disputes.

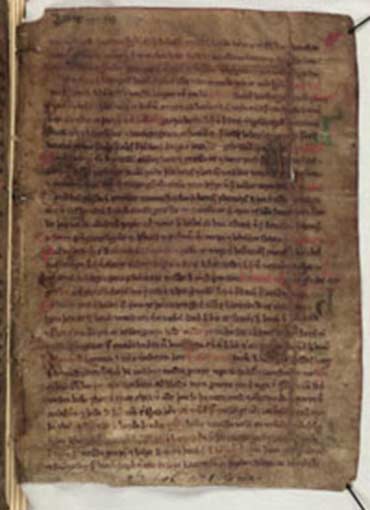

The Icelandic tradition started orally. Stories about ancestors and their culture were passed down from generation to generation with the highest pride. But by the time the 12th century arrived, the country shifted their history from oral traditions to written documents.

Two written documents symbolize the birth of writing for the country and culture of Iceland. These works are called Landnámabók and Íslendingabók. The books were written in the famous language that derived from the Vikings, called Old Norse. Íslendingabók is also known as the most influential book of Iceland’s proud history. It was called “The Book of Icelanders” and was a chronicle of the discovery of Iceland as well as its history till the year 1118.

It’s speculated that the book was researched and created over a decade of thorough investigation between the years of 1122 and 1132. The research was done by an Icelandic noble by the name of Ari Thorgilsson. He was a renowned priest from the Snæfellsness settlement.

During his research, Thorgilsson heavily used his most trusted sources to dive into the oral traditions of his culture and tradition. He backed up the stories of the historical evidence with more recent events that were accounted for by multiple eyewitnesses. Ari was careful in establishing the reliability of his information.

He religiously documented his resources and carefully separated Christian influence as well as supernatural experiences. Even though it isn’t proven, it’s also believed that Mr. Thorgilsson was the author of the second early work called Landnámabók, which is also known as “The Book of the Settlements”.

This supplied painstakingly specific background checks into the details of the land claims across the first Norse settlements, where hundreds of Iceland’s original inhabitants massed.

The research provided a rich history into the country that was founded by the Vikings.

The very first Viking to discover the country was named Gardar, who came from a Swedish background.

In the year 860, he started a journey from his home, the country of Denmark, into the Hebrides. His mission was simple – he was going to claim the land that he and his wife received through inheritance. As he was cruising through the straights of Pentland Firth, he was flushed out into the Atlantic by a powerful storm.

Before the storm, he was situated between Scotland and the Orkney islands; by time the sea settled down, Gardar was lost at sea.

But he was a Viking: he stayed smart and saw this as an opportunity to frontier across unknown territory across the region. Gardar kept cruising through the sea until he became the first known person to discover a powerful coastline ruled by mountains.

Gardar was originally thrilled as he saw the newly discovered land, but after some investigation, he realized that the land was not as habitable as he had hoped. He found himself on the Eastern Horn, the southeastern coast that was almost like a fortress. It was filled with cliffs and giant slopes that tumbled into the sea.

Luckily, the Viking sailor was determined to discover more about the land. He sailed westward across the entire coast, discovering that the land was, in fact, an island. He spent about a year during his exploration of the island before he set sail again during spring time.

Sadly, the small boat that was accompanying his ship drifted away, and Gardar had to abandon his ship to rescue them. On the small boat was a man by the name of Nattfari as well one of his slaves and a bondswoman. These three Vikings became the first inhabitants of the land and survived in the country’s rugged land.

After some contemplation, Gardar named his island Gardarsholm, or Gardar’s Island. He set forth to Norway so he could spread the word and praise the validity of his discovery. Around the same era, another Viking found himself in sight of Iceland. His name was Naddod. He found the island as he was sailing from Norway to the Faeroe Islands. He was blown off course, which leads to his discovery. Naddod first set foot on the land across the island’s Eastern Fjords.

Naddod was quick to search for inhabitants. He conquered a mountain he found in his search for signs of life but was forced to leave during a strong winter storm. Like Garder, Naddod’s return sparked a favorable review of the land, but he gave the island a more modest name. He declared it as Snæland, which means Snowland.

Naddod’s return sparked a quick bolt to the island, fronted by a Norwegian named Floki Vilgerdarson. He set sail from Rogaland with the goal of settling on the island. Vilgerdarson was renowned as a fearsome warrior, but his attempts at settling were futile. He did not have the skills or supplies to survive in Iceland’s difficult conditions.

During the summer, Floki focused his attention on hunting seals throughout the northwestern part of Iceland. During his ventures, he disregarded any need to produce hay. The final result was the starvation of his livestock over the course of the winter.

The result was the undermining of any hopes of permanently settling on the island – Floki was in a predicament. Ice had packed up in the fjord, leaving him stranded on the island. When the ice broke apart enough to sail home, the journey had become too much of a risk, and he returned to the comfort of his home in Norway.

Vilgerdarson had no choice but to live on the island for another winter. As a last ditch effort, Floki moved south to Borgarfjörður.

As a result of his time on the island, the Viking chose to rename the land Snæland, which directly resulted in the country’s current name of “Iceland.” While Floki’s name was an overreaction to his time in a single area, the name stuck throughout history. The Viking’s men gave a much more favorable outlook on the island, as most of the men were excited about the new land. The most excited man was named Thorolf, and he told tales of butter practically dripping off the blades of grass. His tales ultimately shaped his name forever. He was from that point forward known as Thorolf Butter.

After further investigation, it was speculated that the man was born an optimist. Iceland was, in fact, very difficult to inhabit. The land is nothing but an island that was created from volcanoes under the sea. The magma throughout the mid-Atlantic ridge rose up to slowly push away the continents of America and Europe.

Iceland sits south of the Arctic Circle, so it’s expected to be incredibly cold. Luckily for the Icelandic settlers, the Gulf Stream flowed through the island, keeping the land conditions much milder than the rest of the area. Almost 15% of the land is covered with sheets of ice and glaciers, while the rest of the island is far different than the permanently-frozen conditions. While the landscape in Iceland is beautiful, the land is incredibly unforgiving to its inhabitants. But the diverse land felt like legends to the Norse culture.

The combination of fire and ice reminded the Vikings of their mythology. It was believed that the world had surfaced inside of the gap that lay between the realm of Muspel (which is the realm of fire) and the realm of Niflheim (which is home to the ice realm).

Currently, only 25% of the country has vegetation. The rest of the country that’s glacier-free flows with fields of lava or sits in deserts of ashes.

Luckily for the Vikings, when they discovered Iceland approximately 40% of the island had been covered with vegetation. Half of the island was filled with birch and willow, giving the new settlers a much more optimistic outlook of the country they had discovered.

European settlement of the island was considered distinctly marginal. Regardless, the island turned out to be a little more chaotic than first expected. The land was filled with extreme weather conditions as well as dangerous volcanic eruptions with little warning.

Accounts of the island were swirling around Europe, so two foster brothers by the name of Ingolf and Hjorleif chose to scout the land and landed on the Eastern Fjords during the second half of the 860s.

Their goal was to give a proper assessment of the ability to create a settlement on the island. The brothers were desperate. They went broke due to paying off jarl Atli of Gaular. The two had brutally killed the man’s children, and they needed a safe haven to keep their lives. After they had scoped the land, the men appreciated their chances for survival compared to their odds back home. They began to make plans to emigrate to the island. Ingolf had enough resources to set forth on a successful expedition, but his brother Hjorleif was lacking the tools to successfully set out, so he made a víking trip to the island.

While the land was mostly uninhabited, the Viking’s tradition for conflict created violence on the island. Hjorleif set forth to steal a massive hoard of treasure and successfully raided a souterrain and took hold of 10 Irish slaves en route to Ireland.

According to the written records in Lándnámabók, the two foster brothers Ingolf and Hjorleif left their home in 874, proving the validity of the book.

The layer called the landnám layer is found across most of Iceland. It’s a perfect point of reference because the layer was dated to approximately 871 or 872. Studies have proven that human impact on the island was non-existent below the layer but was discovered above the layer.

Once the brothers made their way to the island, they had differences of opinion on how to proceed. Ingolf paid his dues to the Norse gods and in turn gained a favorable future. On the other hand, Hjorleif did nothing of the sort. He skipped the sacrifices altogether. The brothers sailed together until they reached the island and then chose to part ways at landfall. Ingolf was a very traditional Viking when it came to the culture’s mythology. He began looking for guidance from the Norse gods and went as far as to throw his carved pillars out of his ship. Wherever they washed to the shore is where the Viking would settle.

The gesture took Ingolf three years, but he finally found the pillars.

Hjorleif chose to spend his first winter in Hjörleifshöfði. His first goal was to sow crops. He only purchased a single ox, so his slaves were used for plowing the fields. To Hjorleif’s dismay, the men revolted and murdered their owner in cold blood. Hjorleif and his men were nothing but a memory as the slaves sailed off with the women and resources. They made their way to a series of islands that were located off the southwest of Iceland.

But the murder wasn’t kept secret for long. Inhofe’s slaves were searching for the pillars across the coast and made their way to the Hjörleifshöfði settlement. They found Hjorleif and his men. The murder disheartened Ingolf, but his ultimate response was simple – Hjorleif did not sacrifice to the gods, and ultimately they turned against him.

Ingolf set out on a mission to avenge his fallen brother. He speculated that the slaves had made their way to Vestmannaeyjar, so he followed suit. Ingolf used the element of surprise to ambush the Irish during dinner and murdered some. While Ingolf didn’t murder all of the Irish men, he still paid them justice. The others had perished trying to leap off of a cliff in panic. They tried to escape but died from the jump.

Ingolf had stayed smart during his time in Iceland, and after spending three years searching for the pillars, he found his home during the third winter on the island. He named his establishment Reykjavik, which means the “bay of smoke.” The name came from the wonderful hot springs that were located inside of the area. The efforts at this settlement thrived and ultimately it serves as Iceland’s capital to this day.

In turn, Ingolf chose to claim the entire Reykjanes peninsula that was located west the River Öxará.

As his home and followers grew, he established a settlement of 400 original inhabitants. The Landnámabók supplied the names of all 400 of the leading settlers, and even included 3,000 early inhabitants who made their way across the ocean into Iceland’s mystical land. While the documented accounts of settlers only included Norse men, they also brought their families, slaves, and even dependents.

It’s speculated that up to 20,000 people had made Iceland their permanent home by the year 900 (only 30 years after its first permanent inhabitants). By the 11th century, approximately 60,000 people were living on the island, all but securing the property claims of the inhabitable land inside of the island.