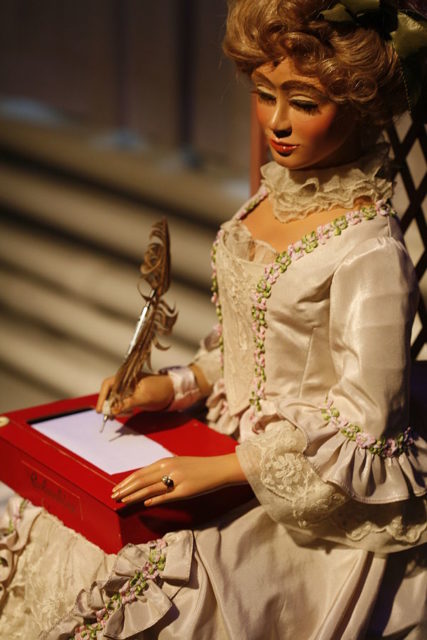

The inventor of this clockwork wonder was unknown until November 1928. It is on display at The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia and operates during performance and demonstration. A truly fascinating mechanism, able write poems and sketch drawings.

The Franklin Institute received a badly damaged machine which had suffered heavy fire damage. The machine resembled a seated boy in tattered clothes with a pen in its hand.

The Brock family that donated the parts on that faithful day in 1928 knew that the brass boy was able to write and draw pictures. They also claimed that it was made by Maelzel, an inventor from France.

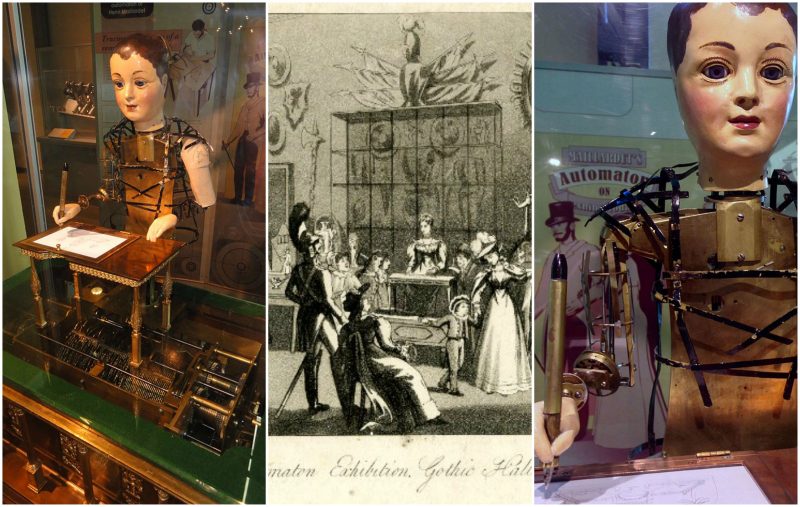

After figuring out the clockwork, the institute repaired, reclothed, and restored the machine to its proper working order. To the staff’s shock and amazement, it began to draw and write with the capability of a human being with flawless motion. When the mechanized boy finished the last recorded poem, it wrote “Ecrit par L’Automate de Maillardet”, which meant “written by Maillardet’s automaton”.

The brilliant machine was formerly known as “Draughtsman-Writer”. It was built by Swiss clockmaker Henri Maillardet in the 18th century. During this era, the public was generally fascinated by clockworks and complex mechanisms that could imitate human abilities.

The mechanical inventions were called “automata”. Watchmakers were making automatons of their own using them as examples of their craft and innovation.

Before it’s final destination at the Franklin Institute, the mechanical boy was well traveled. Maillardet was happily exhibiting his glorious invention throughout Europe, England, and Russia, astonishing crowds along the way. Luckily for the institute, it could have been destroyed, stolen, or lost during its long trips. Its intact existing is still a wonder.

Maillardet’s invention undoubtedly stands out from the other automatons for its capability of storing read-only memory, similar to today’s computers, as seen from the three poems and four sketches. He also made another automaton that was able to write Chinese letters and was used as a gift for a Chinese emperor from King George III of England. Reportedly, Maillardet probably auctioned the invention in Philadelphia to pay off his debts.

The way automatons worked, their coordinated motions and the clockwork’s blueprints were all a well-kept secret among the clockmakers. It took an excruciating amount of time to figure out the basic functions of Maillardet’s machine, as it was undoubtedly the finest example of automaton clockwork and a pinnacle of a high-quality craft.

It is amazing to see the machine in its full splendor even after 200 years. Its fundamental driving mechanism that used cams was at the base of the machine. It contained brass discs with curved edges that were driven by the motor, with three “fingers” smoothly following along the curves.

Using wind-up motors, the complex coordination of the curves, edges, and levers was a true marvel of precision. It stored the very same poems and images and they added up to approximately 300 kilobits of storage.

The motions were not jerky or sudden, yet, smooth and startlingly lifelike. Even the eyes and head motions were controlled by other cams, which proved the clockwork’s impeccable precision and added to its lifelike behavior.

The automaton would pause its writing at a certain moment, gaze in the distance as if contemplating how to draw the sketch.

A brilliant synthesis of art and science, Maillardet’s automaton is regarded as a true wonder of a clock worker’s skill and labor. It stands out because of the inventor’s attention to detail and the endeavor to make it as lifelike as possible. Maillardet could have easily settled for a head and eyes with a motionless, fixed position. Instead, he chose to create a replica of life, a glorious attempt to revive Collodi’s fables.