A black tea with sugar or milk served in the afternoon might sound like a cultural signature of the British, and a warm and tasty beef stew may be perceived as something typically Irish. In the case of the Scots, it is not food but rather a type of textile that forms a signature of its culture, one both recognized beyond its borders and adored by any traveler who happens to come to Scotland.

However, even though we have for centuries associated tartan with this country, looking into the past shows us that this textile was also present in other geographical areas of the world, and long before the earliest traces of it–the Falkirk tartan fragment dated to the 3rd century AD–were unearthed near Falkirk, in the Scottish County of Stirling.

The Falkirk piece is considered a rudimentary design, one that has both light and dark wool, and it was found crammed into a pot which contained around two thousand Roman coins. The finding was located close to a section of the Antonine wall.

Much older pieces have been found both in the vicinity of Salzburg, Austria, and as far as China in the Xinjiang province. According to E. J. Barber, an expert on the history of textiles, it was supposedly ancient groups of Celtic people who produced tartan, possibly before their migration from Central Europe to the north (their assumed migration), which would explain the existence of some remarkably preserved samples of tartan unearthed in 2004 near Salzburg, as far back as the 8th century BC, and found on the site of the Hallstatt salt mines.

It seems even more challenging for experts to explain how the tartan-like textile made it all the way to China, but indeed, traces of it have been found on the famed mummies of Tarim, in Xinjiang. The Chinese examples are dated to a bit later than the Salzburg ones, and analysis has shown striking similarities between the two distinct findings so distant from one another.

According to the New York Times, the Xinjiang samples are some of “the most intriguing textile samples from the late second millennium B.C,” unearthed in China. This clothing, de facto, has rarely been associated with this geographical region, and certainly not for this period. A possible explanation is that it came here following waves of migration that likely occurred around the 2nd century BC, introducing this material to the Far East.

The early pieces of tartan clothing produced usually had a very simple design. They were often dyed in two colors only, and their makers made use of a dye extracted from specific plants, berries, or trees found in the vicinity where the tartan was woven. That perhaps explains how later on, particular colors of tartan became signature attire of distinct clans across the Scottish Highlands.

Also, in the past, other wordings were used to describe the tartan, such as “mottled” or “marled,” or “striped” and “sundrie colored.” The modern word used today comes from the French tartarin, which traditionally refers to a specific type of checked clothing. It is further interesting to note the word Breacan, which stands for checkered in the old Gaelic dictionary.

The tartan items of clothing that we associate with modern-day Scotland can’t be traced earlier than the 16th century. In the Highlands, it became a standard piece only in times after that, and it was also when this fabric emerged as a symbol of the clans.

Not only did mere mortals wear tartan, the Royals did too. For instance, in the 1500s, when King James V of Scotland went hunting in the Highlands, he chose to wear tartan. In 1662, King Charles II even placed a ribbon of this fabric on his wedding coat.

All was well with tartan during the 16th and 17th centuries. The fabric moved from the Highlands to the south of the island, and it also had a fixed priced, depending on the coloring, to avoid cheating and overcharging. More documents suggest that some people even paid their duties to the government with this material.

At least that was the case until 1746, when the Battle of Culloden led to a fiery confrontation between the Scottish and the English armies. Since the English won, the London-based government had reportedly purged the Highlanders, passing an act that forbade clan members from carrying a weapon and wearing clan tartan.

That is considered to have been a vigorous enforcement that lasted until 1785, by which time, a considerable number of original tartan patterns and designs typical for distinct Scottish clans were lost.

Thankfully, the fabric has significantly returned to popularity in Scotland following a visit by George IV to Edinburgh in 1822. The king used the opportunity to encourage people, specifically those holding official posts, to put on their respective clothes of tartan. At this point, due to the earlier loss of authentic patterns, tailors allegedly needed to come up with some new designs, many of which are likely the ones we see today.

Under Queen Victoria, the popularity of tartan continued to grow, the queen herself having been noted for her fondness for almost everything that came from Scotland. Since her reign, and to date, the tartan fabric has shown to be of considerable importance to the Scottish economy.

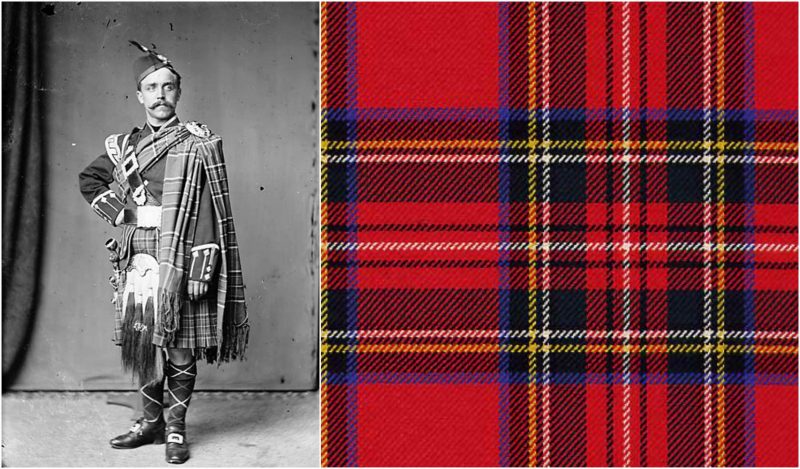

The tradition of clan tartans is still alive and well today. The Mackenzie tartan, one of the most popular ones, which was first worn as a uniform among the Seaforth Highlanders, the British Army infantry regiment from Northern Scotland, as established by the Earl of Seaforth in 1778, can today be spotted on the Pipes and Drums Band of the Royal Military College of Canada.

Another is the Royal Steward tartan, which is the personal tartan of Queen Elizabeth II, and the Black Watch tartan, also known as the Old Campbell, this one is still used by a couple of different military units operating throughout the Commonwealth.